There has probably been no more romantic human dream than the wish to fly. To defy gravity is to break through the bounds that tie we humans down. It is death-defying, an expression of immortality. Anyone who gets on a plane today and does not think – irrespective of what knowledge of aeronautical physics they may possess – that this cannot logically be happening, has forgotten a part of their humanity. To fly is to be transcendent; that is, until the reality of our condition comes upon us, and Icarus-like we fall.

The earliest aviators lived this dream most fully. Never again would the sense of exhilaration and transformation be so acute, nor the perils so great. They were revered in their time for the gift they gave to the imagination of all, but also for the dangers they faced. The line they flew veered with giddy unpredictability between death and immortality. They had the quality of myth.

Not too far away from here, on the north-western side of Kent is the pretty village of Eynsford, a few miles north of Sevenoaks. Head for about a mile along the winding road from the railway station that leads south and upwards past and you get to Upper Austin Lodge. Close by this cluster of houses and farm buildings, next door to a private golf course, is where Percy Pilcher conducted many of his aviation experiments.

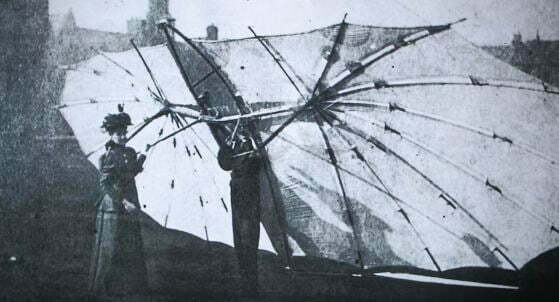

Percy Pilcher, an engineer and a lecturer at the Department of Naval Architecture at the University of Glasgow, was a devotee of the German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal, who first convinced the world that human flight using fixed wing aircraft was possible. Pilcher constructed his first glider, ‘The Bat’, in 1895, the year before his hero Lilienthal was killed flying one of his gliders. He joined up with fellow flight enthusiast Hiram Maxim, a man who had done more than most in the cause of human misery by having invented the machine gun, from the profits of which he pursued his interest in flight. Maxim had a hangar constructed at Upper Austin Lodge, where the secluded area with its gentle slopes offered an ideal location for Pilcher to conduct his glider tests, over 1896-97, on a nearby hill known as ‘The Knob’.

Having got to Upper Austin Lodge you are faced with a fork in the road. Choose the left-hand route (there is no signposting), heading past the Lodge itself, then on down a country path before 400 yards or so, before a sign pointing right directs you to the ‘Pilcher monument’. You travel some 400 yards further up a narrow path lined with fencing (to prevent you straying anywhere near the golf course). At the top of the slope, looking out over the rough hillside to the trees and slopes beyond, in a fenced off area (topped with barbed wire), there is the Percy Pilcher memorial, unveiled in 2006 and recently moved to its well-protected new location. There is a rock with a plaque memorialising Pilcher’s achievement, and a board with text and images providing more information. Though awkward to find, the memorial is fitting, and the location apt. Look about you – from here, man took to the air.

And woman also. One of the interesting aspects of Percy Pilcher’s aviation experiments was the female collaboration. His sister Ella worked closely with him in the study of the principles of flight and the construction of his various gliders (she did much of the fabric work). His cousin Dorothy Rose Pilcher was involved in that part of Pilcher’s flights which first attracted me to him, when he became the first person to be filmed in flight.

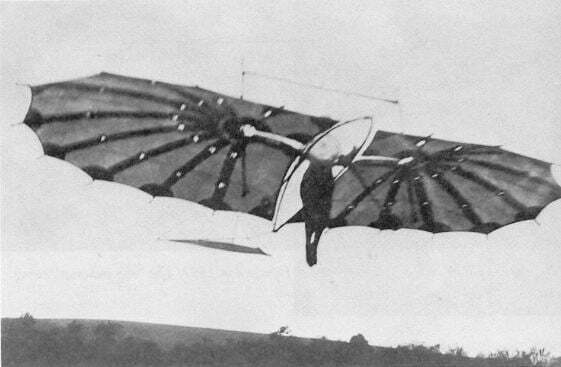

The occasion was 20 June 1897, when Pilcher flew for the press, over a distance somewhere between 150 and 250 yards, with the goal of attracting publicity and funding. On that day a film was made of one of the flights, very probably by aviation enthusiast and photographer William J.S. Lockyer. Lockyer’s film, which is likely to have been made as a scientific record i.e. with the goal of having individual frames to illustrate the parts of the flight, rather than for the sake of showing movement per se, does not survive. However, seven frames were reproduced in the scientific journal Nature (12 August 1897 issue), and a few years ago I animated these and put the results on YouTube. The image quality is poor (scans from a digitised journal), and the action covers only a split second, so that I had to show the flight repeated numerous times. But even seven frames can give you a semblance of life, and there is Percy Pilcher, being pulled into the air by use of a towline, over and over again.

Percy Pilcher flying ‘The Hawk’ glider near Eynsford, 20 June 1897, animated from seven frames reproduced in the journal Nature

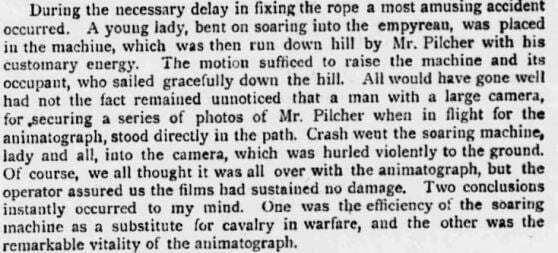

It is known that Dorothy Rose Pilcher also flew that day, quite probably the first woman anywhere to fly a heavier-than-air aircraft, though it is possible that Ella Pilcher could have preceded her. We know of this because of a long report on the events of that day in the Pall Mall Gazette of 29 June 1897, which reports on how a woman flying a glider (unnamed, but subsequently identified as Dorothy by the family) crashed into the cinematographer as she was landing.

There are many points of comparison between the first flights and the first films. Both histories have at their heart the success achieved by two brothers (the Wrights and the Lumières), both occurred around the same time, and several of those involved in their invention had a foot in both camps: French chronophotographer Etienne-Jules Marey, whose chronophotographic studies paved the way to motion picture film, studied bird flight and collaborated with flight pioneers Victor Tatin and Alphonse Pénaud; Antoine Lumière, father of Auguste and Louis, was taught photography by balloonist and aviation visionary Nadar; Lilienthal was inspired by photographs of storks taken by German chronophotographer Ottomar Anschütz, who in turn photographed Lilienthal’s glider experiments; and Octave Chanute, influential in supporting Orville and Wilbur Wright’s aviation experiments, was a keen follower of Marey.

I wrote an essay on the connections between the first films and the first flights back in 2004, which describes other connections and lists the early flight films that followed after Pilcher’s (the Lumières were the first to film from the air, from a balloon, with Panorama pris d’un ballon captive in 1898, while the first aeroplane filmed in flight was the 14-bis of Alberto Santos-Dumont, filmed 23 October 1906 by I not who. The Wright brothers’ first flight on 17 December 1903 was not filmed, by the way). It’s an engrossing shared history, in which the ambition was not just technical but metaphysical. Both made the impossible possible – defying gravity, and recreating life. Both are an illusion, of course – the semblance of life ends when the reel spools out of the projector, and all those who dare to rise from the earth that binds them will eventually be brought down. To have the two combined, as they were for the first time in 1897, is magical. It is a marriage of the imagination. After this, we can achieve anything.

Percy Pilcher died of his injuries on 2 October 1899, two days after his ‘Hawk’ glider crashed to the ground at Stanford Hall, Lutterworth in Leicestershire. He had developed a triplane and was working his way towards powered flight. Had he lived, he might have beaten the Wright brothers to that great goal, and the Eynsford memorial would be a good deal more prominent than it is. There is another stone monument, in a field at Stanford Hall, marking where Icarus fell.

Links:

- The best source of information on Percy Pilcher is Philip J. Jarrett, Another Icarus: Percy Pilcher and the Quest for Flight (Smithsonian Books, 1987). It has plenty on the filming episode

- There is a website dedicated to the Eynsford Percy Pilcher memorial, www.pilcher-monument.co.uk

- National Museums Scotland (Percy Pilcher was based for much of the time in Glasgow) has a good illustrated guide to the ‘Hawk’ glider (which it holds), noting Ella Pilcher’s contribution to the work. It includes a video which includes a conversion of a still photo of the glider at ‘The Knob’ into a motion picture

- There was a BBC Horizon programme on Percy Pilcher, broadcast on BBC Two, 11 December 2003. The programme page, with summary, transcripts, questions and answers and links (but no clips) is available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2003/percypilcher.shtml

- My essay ‘Taking to the Air: Early Film and Early Flight‘ is available on this site. See also my Bioscope blog post from 2011, ‘First Flight‘, about animating the seven frames and the surviving film records of early aviators

Hi,

In your entry for Tsunekichi Shibata, you list his first work as dating from 1899. You might also want to mention that contributed films 981-985 in the Lumière catalogue having been commissioned by the Lumière company.

See https://catalogue-lumiere.com/operateur/tsunekichi-shibata/

By “your entry” I was referring to your Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema website.

Indeed I have too many websites. I hadn’t picked up on Shibata filming for the Lumières before now. I shall investigate further. Thanks for letting me know.

So many websites, so little time.

I learned about Shibata’s shooting for the Lumières on a Polish website then searched and found him listed on the catalogue. There’s now a rather marginal copy of his Maple Leaves Viewing on Wikipedia, but it’s the earliest thing from Japan I have been able to access. Do you know of anything earlier which still exists?

I think all of the Japanese subjects filmed for the Lumières exist. Certainly that’s what’s recorded in the Aubert/Seguin catalogue La production cinématographique des Frères Lumière, which is the basis of https://catalogue-lumiere.com. That includes the 1897 films filmed by Constant Girel. I know of nothing that survives earlier than those. Edison films filmed in Japan survive from 1898. Viewing Scarlet Maple Leaves was filmed in November 1899. It’s wonderful that the film can be seen by all. I wrote about the film here: https://lukemckernan.com/2010/05/11/viewing-scarlet-maple-leaves/

What I meant was other films shot in Japan by Japanese filmmakers. As your entry in WWVC states, Shibata made geisha films and The Lightning Robber is arrested before Viewing Maple Leaves. What I was trying to ask was: do any Japanese films earlier than Viewing Maple Leaves survive?

Only the four Shibata Lumière films from 1898 that you identify, so far as I know.

I have now updated the Shibata entry on Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema, with acknowledgment.

None of this has any connection with Percy Pilcher, of course.

Glad to see the update. Thanks for the acknowledgment.