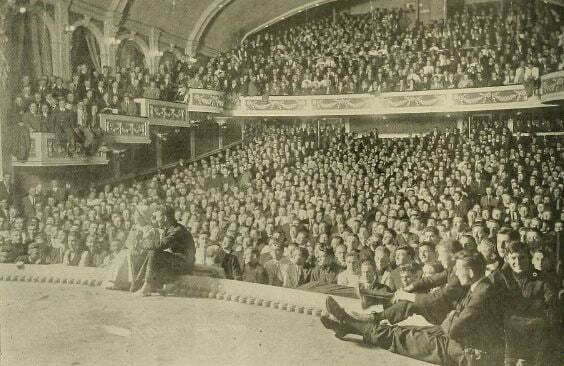

What a magical image this is. An audience of young people has packed a theatre, to such a degree that some are on the stage, while others sit perilously on the edge of the balcony, their legs hanging over. They are fresh-faced, eager, revelling in where they are and who they are. A man and woman are seated at the edge of the stage, backs to the audience. Perhaps they are part of the audience, perhaps part of the entertainment. There are no other women to be seen in the stalls, but some are seated in the circle. Is this accident or purdah? All faces are lit by a bright flashlight, but look in different directions, suggesting that there was than the one photographer present for whatever occasion this was. Our photographer has captured an angled view from the stage. It is dramatic, mysterious and filled with optimism. It lifts you. It makes you want to be there.

I found the photograph while working on a filmography of the early colour process Kinemacolor (a project that is going to take quite some time to complete). It shows students from the University of Michigan at the Majestic theatre in Ann Arbor, around August 1913, watching (so the caption informs us) the Kinemacolor Company of America production Steam (1913), a three-reel documentary on how steam engines were develped by James Watt and George Stephenson. The film gained good reviews at the time, in part for its novel combination of actuality with dramatic sequences. Like most Kinemacolor films, it does not survive today.

The Moving Picture World, from where I found the image, tell us that the “this reel was of special interest to the students of the University of Michigan, and shows how the brainy and ambitious youths of the country respond to every opportunity to learn something – even from the moving pictures.” That’s a tad dismissive of the value of the medium from a journal supposedly devoted to its promotion, but the students seem to be relishing the occasion. It was presumably deemed special, meriting the flashlight photography and all of the complications involved in setting that up. I’ve not been able to find out anything more about the event, but Kinemacolor films were shown regularly at the Majestic and occasionally at other Ann Arbor locations as part of mixed entertainments. It’s possible that there was a live stage entertainment element to this Kinemacolor show, which might explain the couple at the front. But the picture is no less the haunting for our not knowing everything about it, and maybe all the more so.

Images of film audiences tend to share common features. They shown faces lit up by the unseen screen, capturing their rapt look before the magic of cinema, in an act of worship. That the faces are usually looking up accentuates this sense of worship, which could be viewed as religious or else the trusting child looking up to its parent. The images are the wish fulfilment of filmmakers, and occur memorably in films such as Sullivan’s Travels, Brief Encounter, The Long Day Closes and Hugo. It is an impossible image, because no one sees the audience from the screen, except for those unreal folk who populate the screen. It is a projected view; which exists only because it can be imagined.

In practical terms, such images can be taken in real life. They are invariably at an angle to the audience, if they are showing people actually watching (as opposed to waiting to watch, as we see with Ann Arbor), for the simple reason that the camera cannot be placed in front of the screen without interrupting what is being watched. This can be done covertly. There was a notorious case in 1950 when Picture Post magazine published infra-red photographs of children watching the serial Jungle Girl at the Tooting Granada. The scenes of apparent distress, with images presented wholly out of context, caused much angry comment from those who would far rather children did not go to the cinema at all. A much more controlled experiment, funded by the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust and organised by Mary Field, head of Rank’s Children’s Film Department, used infra-red to show the responses of children to different kinds of film in a number of cinemas across the UK in 1951/52. Careful contextualisation (the above image shows Dunfermline children in anticipation of a challenging plot development) and publication in a respectable book (Children and Films: A Study of Boys and Girls in the Cinema [1954]), ensured there was no controversy second time around.

The Carnegie/Field images were scientific in intent, but not in their effect. They could be used to infer almost anything, depending on your prior prejudices. Their real intent was that wish to grasp the impossible: the mind of the audience revealed through the face of the audience. Its value lies in being something that is beyond us, that we cannot see. Actually seeing the audience destroys that. All that remains is the intrusion.

What we see when we see the face of the audience is ourselves. We see our fears (as the Picture Post photos revealed) and our hopes. We recognise what it is to be transported, and to be alongside others similarly transported. We find what is hopeful in ourselves. It’s that which links the students at the Majestic in 1913 with Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (in which our filmmaker hero finally learns to laugh alongside the common folk watching a Disney cartoon) and with Syrian refugee children watching Tom and Jerry in a makeshift screening set up by volunteers at a Budapest railway station, images of whom were widely distributed back in 2015.

Anyone with a heart sees themselves in the faces of that child audience. That was what was so powerful about the Budapest images. They showed what we hold in common. Borders keep us apart, but Tom and Jerry breaks those borders down. That is what we wish for, all of us. Of course the reality is more complicated, but we weren’t seeing the political complexities; we were seeing ourselves. All audiences must be alike, and how powerful is our need to be a part of one.

Links

- The image of the student audience watching Steam can be found on Moving Picture World, 30 August 1913, p. 966, courtesy of the Media History Digital Library, and separately on my Flickr pages

- Advertisements for, and accounts of, Kinemacolor shows at Ann Arbor can be found on the University of Michgan’s long-running student paper The Michigan Daily – an excellent example of a digitised newspaper resource, though sadly with no coverage of the Steam event

- Photographs of the Syrian refugee children at Keleti railway station in Budapest are reproduced in the Independent article ‘Volunteers at Budapest station set up projector showing ‘Tom and Jerry’ for refugee children‘ (3 September 2015)

- There are some images of cinema audiences, real and fictionalised, included on my Picturegoing site, which documents eyewitness accounts of viewing pictures