Does the road wind uphill all the way?

Yes, to the very end.

Will the day’s journey take the whole long way?

From morn to night, my friend.Christina Rossetti, ‘Uphill’

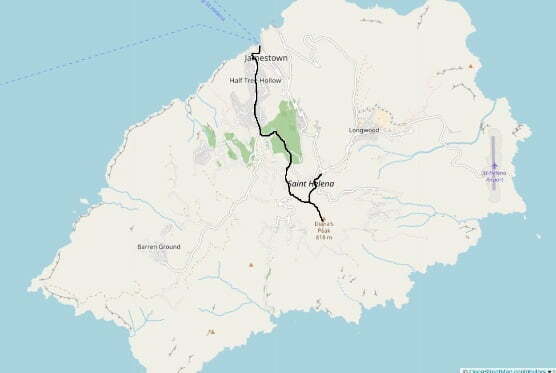

When I was on St Helena, I undertook the finest walk that I have ever experienced. This is the story of that walk.

It was the 18th of March, 2018, the dawn chorus of mynah birds echoed throughout Jamestown, and the early morning skies were grey. March marks the height of the St Helenian summer, but the weather on the island is ever changeable. A light rain could be falling here, but the sun would undoubtedly be shining later on and further inland. It was going to be a fine day for the walk. Walking boots, some provisions, a bottle of water, camera, map, suntan lotion (the sun can be fierce when it does shine), guidebook – and we’re ready.

Jamestown is by the ocean. For our walk we are beginning at sea level and making our way to the highest point of the island, before descending. So you must go to the seafront, contemplate the immensity and the isolation, then turn back into the town and right by the museum, at the back of which and before you is the daunting prospect of Jacob’s Ladder.

Climbing Jacob’s Ladder in 21 seconds

Jacob’s Ladder is a 699-step stone stairway which rises 600 feet up the stark, steep rock face leading to Ladder Hill above. Its first version, referred to as an ‘inclined plane’, was built in 1829 and was used to haul manure via a pulley system operated at the top by mules. The original construction was devoured by termites and replaced by the stairway we have now in 1871. It’s hard to imagine it having ever been used by the locals in the usual run of things (there is a road that runs precariously up the cliff), but it is a practically obligatory right of passage for all visitors. You see them from a distance launching out with great confidence, then about a quarter of the way up starting to stagger, pause for long rest breaks and generally regret both their condition and the fact that they are trapped and have no option but to continue, in pain.

But we are smarter. We know not to launch into such a climb too soon, but to have acclimatised ourselves. We climb steadily (taking a photograph every dozen steps for the planned stop-motion movie), with a couple of rest breaks along the way to take in the view, naturally, which is stupendous. The ordeal is made greater by the steps being as high as they are wide, while the gradient shifts, becoming steeper. Yet we plod on, even while heart, mind and gravity all argue against us.

And then we reach the final step. It has taken 25 minutes, rest-breaks included, and the sense of triumph is absolute. We can conquer anything now. We own this island.

At the top of Jacob’s Ladder you find Ladder Hill Fort, with its shabby, neglected battery and exhilarating views over the ocean and narrow James valley, where Jamestown is squeezed thin between the brown and brutal walls of rock on either side. But we have only just begun our climb, because as we turn around Half Tree Hollow faces us.

Half Tree Hollow is Jamestown’s suburb, though it is actually more populous that the island’s main town. It presents the most extraordinary sight. Before you lies a rocky hill face out which hundreds of single-storey homes have been positioned, each facing the ocean and the sun. The sheer untidiness of Half Tree Hollow amazes. The individual homes themselves are fine in themselves – of special interest because they are so very much the preferred St Helenian style, giving much of the built-up areas their distinctive character. But so little care has gone into making the sites on which the houses sit in any way attractive. Each looks to have been carved out of the unforgiving land and left the land looking as unforgiving as they found it. There is almost no grass. Nor do the houses connect with one another. It is a hillside sprawl and defiantly so, visually quite striking when seen from higher up or from the air, but unprepossessing below.

Maybe there is a rough beauty to some of it, but now we must climb, because all of this is mere preamble. Our walk has not yet properly begun. We must walk up through Half Tree Hollow, and it is a challenge in itself. The road is long, steep and unforgiving. But we have prepared for this. The walk would have been unwise too early in our stay, but after a week of climbing slopes in our exploration of the island, we have discovered the optimum pace and style. We have our St Helenian feet. A sensible plod has been learned, leaning forward slightly, maintaining a patient rhythm, progressing with steady purpose.

Travel writers, psychogeographers and philosophers of walking seldom mention walking uphill. The art of walking is generally assumed to be something that takes place on the flat, where reverie may take over and ideas flow. Walking, in this frame of mind, is a creative act, conducive to and analogous to the act of writing itself – the external expression of an inward discovery. Yes, there is mountaineering literature, but that is a different kind of walking, one which revels in its exceptionalism. My impression is that the mind going uphill initially thinks only of going uphill. It concentrates wholly on the task in hand, banishing productive thought. But practice, and accommodation to the demands of gradient, eventually bring about not only greater physical ability but the return of an active mind that may even finds itself in a better state. Frédéric Gros, in his A Philosophy of Walking, does not address uphill walking per se, but he does state this:

[W]alking is always a perception of gravity … walking reminds us constantly of our finiteness: bodies heavy with unmannerly needs, nailed to the definitive ground. Walking doesn’t mean raising yourself, it doesn’t mean getting the better of gravity, or letting speed and height delude you of your mortal condition; it means reconciling yourself to it through that exposure to the mass of the ground, the fragility of the body, the slow, remorseless sinking movement. Walking means precisely resigning yourself to being an ambulant, forward-leaning body. But the really astonishing thing is how that slow resignation, that immense lassitude gives us the joy of being.

Walking humbles us, then elevates us. Through acceptance of what it demands of our body and mind, we scale the heights.

The special value of travelling from ground level upwards, on foot, on St Helena, is the transformation that takes place once one has reached the level of around 1,000 feet. St Helena is, on its circumference, a circle of brown volcanic rock. In the centre, however, is the most glorious greenery. It is a Dantean-like journey, where we have trudged our way through Purgatory, and as our reward now see Paradise awaiting us.

So let us get the best view of what lies ahead for us. Having scaled Half Tree Hollow, the pleasant Georgian house Prince’s Lodge lies to our right, one of several such luxuruious homes built by the well-to-do during the period that the East Indian Company controlled St Helena. A hilltop lies to our left, on top which is Hill Knoll Fort, and here we go next. Originally built in 1798, this large fort is positioned at a giddy height overlooking most of the island. One pities the poor soldiers who had to march up here, though their greater complaint was boredom. Aside from a mutiny in 1811 over a reduction in alcohol rations nothing ever happened on High Knoll Fort. The enemy never came. It is in a dilapidated state (as are most of the many fortifications spread across the island), with some parts of the walls out of bounds. But it is worth every footstep getting there for the sweeping views across ocean, valleys and the hill-lands beyond.

We come down again, noting aloes and cacti sprouting on either side of the path, and reach a crossroads. Ahead lies the most pleasant St Paul’s area, with the island’s small cathedral, the governor’s home of Plantation House, the idyllic rolling countryside, and beyond the picturesque Casons Forest. But we are taking a different route. We turn left, following the road downhill into a wooded valley with small reservoirs either side, then climb up the other side to the surprising sight of a open field. This is Francis Plain, and if we have got our timing right (it is just after 10:00 on a Sunday) then a game of cricket is underway. This we have described previously, so we pause only for a while to take in the view (including High Knoll Fort, now towering above us), before we turn again inland.

We go past the Prince Andrew secondary school and on to the surprisingly flat road beyond. Handsomely tree-lined and most pleasant to walk along, we are now entering the green lands. The heart lifts. To our left, tucked within the wooded hillside, is a cemetery for Boer War prisoners, the graves laid out in regimented ranks. We are alone, it should be noted. The occasional car passes by, the driver invariably waving to us (this is the friendliest of places) as we wave back. But of other walkers there are none. It is a fine summer’s day, on a weekend in the summer, but the world is elsewhere. We have Eden to ourselves.

The road turns at Lemon Tree Gut (small valleys on the island often come with the name Gut), then zigzags upwards. On the right rises up the land mass known as The Dungeon, a singularly misleading name for what is one of St Helena’s best attempts at suggesting Arcadia – rolling lands of lush greenery, arrayed in perfect harmony. Is there anything more satisfying to the soul than to be walking through green, rolling countryside? The appreciation of green is, of course, culturally conditioned. Did I not live in a country where there is an abundance of such greenery, kept so through reliable rain, then the heartland of St Helena might not have such a deep appeal. But it is hard to believe that there could be anything more satisfying than to proceed through such uninterrupted natural abundance, a figure in an all-encompassing landscape painting whose mystery unfolds through motion, never entirely resolving itself because we must always be moving on. It is the panoramic effect, where either the scenery may be seen to roll slowly past us, or it is we that are moving. Either way, the magic comes through a counter-balance of stasis and motion. In walking we see the world unfolding, every step a revelation.

It is close to midday. Though we could stroll happily through such pastoral beauty endlessly, the next part of our walk is upon us. We have reached Stich’s Ridge, and from here we will be climbing up to the island’s three peaks, achieving our goal of journeying from bottom to top. We are at Cabbage Tree Road (the cabbage tree being one of St Helena’s most distinctive and common sights), where there is a signpost for the Diana’s Peak National Park.

There is a grassy path, well cared for, which takes us on a twisting route up to the top of the peaks. The vegetation pours in from the sides: cabbage trees, lobelias, ferns, flax. The views out across the valleys continue to enchant us, but the mist is starting to gather, the nearer we get to the top.

There are three peaks along the ridge – Mt Acteon, Diana’s Peak and Cuckold’s Point. There remains debate over which name should be assigned to which of the first and last of those, with old maps disagreeing, but Diana’s Peak in the centre is the highest point, at 2,690 feet (823 metres). Near to Mt Acteon, which comes first, there are steps and rails, for this particular section of our walk is a popular one (though we remain alone today). Parts of the route have needed careful husbanding, not least because the drop on either side of the narrow ridge is a considerable one, and the way is damp. We reach Mt Acteon, distinctive on account of the Norfolk Pine on its summit, and confusing because the first thing that greets us is a sign saying ‘Cuckhold’s Point’. St Helena, make your mind up.

The green path and steps dip down then up again as we reach Diana’s Peak. The views ought to be glorious, revealing the island in its entirety, but we are surrounded by mist, making the narrow space at the top of the peak feel all the more precarious. There is a small bench, and one of the Post Boxes to be found all over the island, marking the end of designated walks where you can find a stamp and ink with which to mark your achievement. So we stamp our guide book, and sit a while, contemplating damp greenery close by and the fathomless grey beyond.

But the best is yet to come. Having let the mist clear a little (walking along a damp knife-edge when you can only see a few feet ahead of you does not feel wise), we could go on to Cuckold’s Point to complete the set, or we can retrace our steps to the point where we started to climb the final steps up to Mt Acteon. Here there is a wooden platform, named Halley’s Mount, after the astronomer, whose observatory is located elsewhere (more of which below). Stretching out northwards from here is a ridge of surpassing beauty, kindly revealed to us by the returning sun. It has the appearance of a giant creature, the spine of some mythic beast ready to rise up at the end of times, whose luxuriant hair falls down the slopes in thick green folds.

In the guide book it says that the path along this ridge is not regularly maintained. It is an unofficial route, and presumably little frequented as a consequence. Yet we are about to launch out upon the most singularly beautiful half-mile or so of countryside that I have ever witnessed (though possibly sharing the honours with Borrowdale, in the Lake District).

There is a path through the folds of greenery that pour down on either side of the ridge. The greenery is formed by flax. There is a long, sad history of people (invariably outsiders) launching myopic economic schemes with the goal of making St Helena financially self-sustaining. Almost all of them have been ruinous failures. The most prominent was the introduction of New Zealand flax, towards the end of the nineteenth century, at a time when the island was in a particularly wretched economic state. Flax production was best suited to a highly-mechanised operation, of a kind not feasible for remote St Helena, but nevertheless considerable swatches of the island were covered with the plant (displacing much of the endemic flora) and many of the inhabitants were involved in the business of converting the flax into fibre for the greater part of the twentieth century. Then in 1965 the British Post Office, with which the island had a contract, chose to switch from flax string to synthetic fibre, and the business collapsed over night. But the plants remained. They can be seen spread over many of the hillsides, blending in with the other vegetation, much of which is itself introduced rather than native. Flora, fauna, people – St Helena is a land of interlopers.

And so we walk through a carpet of flax, falling away to the sides along the path as we pass by, as though at our command. There are epic views on either side, with the island’s verdant heartland laid out below us, encircling us. At the end of the ridge there are woods, which we now enter. It is hard to describe what follows. The path takes us through ravishing scene after scene, as if nature is saying: you thought that last one was good, now look at this. Abundant arrangements of bushes and twisted trees crowding in on one another are followed by trees with fantastical green ferns looking like another planet’s idea of what Earth might look like, to tall Eucalyptus trees rising up with cathedral-like grandeur. If the route past the Dungeon was like some nineteenth-century panorama, now another Victorian optical device applies – a series of magic lantern slides, one dissolving into another, each calculated to raise a gasp with its beauty and intricate detail. It is quite the most breathtaking display, one which plain photographs cannot properly recreate. They miss the presence, the astonishment, the sheer theatricality of it. But here are some anyway:

We have left the woods and begun our descent. Passing down the hillside path, there is a sign inviting us to turn right to discover Halley’s Observatory. In November 1676 the British astronomer Edmund Halley sailed to St Helena, a journey that took him three months. His plan was to map the stars of the southern hemisphere. St Helena was chosen as a suitably located land under British control, specifically the East Indian Company, where the view of the stars was promised to be exceptional. It was a rough place in those days, but Halley built an observatory, and equipped with sextants, quadrants and assorted telescopes did as best he could to map the stars and record the transit of Mercury, though the continual cloud cover made his task far harder than he had been expecting. He spent a year on the island, mapping 341 stars and making many crucial astronomical observations, establishing the foundations of a career that would lead him to become Britain’s second Astronomer Royal and lasting greatness. He was twenty years old.

The observatory, which was only rediscovered in 1968, is nothing but the outline of stone foundations, some of which were built up later as a signalling station. There is now a wooden canopy, in a effort to make it more of a visitor attraction. Looking out from where Halley once stood, we can see in the far distance the runway of the airport, carved out of the barren rockiness of Prosperous Bay. So we contemplate the collapsing of distance and the passing of time.

We come out at the road, turning right beyond a cemetery to find the modest and rather charming St Matthew’s Church, with a comfortable musty smell redolent of a place that has stood there for centuries, though it is in fact a relatively recent building. We are at the area called Hutt’s Gate, at the turning from the road that goes back to Jamestown and on to Longwood. Its most distinctive building – not that there are many – is the pleasing Hutt’s Gate Store (though a store no more).

Our walk is over. We are long way from Jamestown, and our journey has taken some five hours (longer if we stopped off to watch the cricket). With luck we will have timed things to catch one of St Helena’s infrequently scheduled buses, or we have arranged a taxi or some other ride back. Otherwise it is a long hike home (I know, because I walked it).

Why was this walk so successful? For me, it was firstly the combination of climbing Jacob’s Ladder, seeing a cricket match, ascending to the top of the island and finding Halley’s Observatory, all goals that I had set myself beforehand and all achieved in a single day. Secondly it was the unexpected discovery of the ravishing walk along Halley’s Mount. Whether you come down from Diana’s Peak, or up from Hutt’s Gate, a more beautiful path through the finest that nature has to display would be hard to find.

But there was also something mysterious and metaphorical about it. The Christina Rossetti poem ‘Uphill’, whose first stanza is quoted at the head of this post, is about the hard road to heaven. Its final stanza reads:

Shall I find comfort, travel-sore and weak?

Of labour you shall find the sum.

Will there be beds for me and all who seek?

Yea, beds for all who come.

Well, practically speaking, that doesn’t make much sense, because few uphill journeys end with a place where you can expect to find a bed. The beds are almost invariably down below, where you started. But St Helena is a place in reverse. Most uphill journeys begin among the greenery and end up among high, bare rock (or snows). You are rewarded by the views, but seldom by the place itself. St Helena, however, starts with the rock and leads you up into the green. It is the world turned upside down.

The progress is heavenly. That’s what Jacob’s Ladder was, biblically – a stairway to heaven. And who could hope for better? A more rewarding walk I could not imagine to exist.

This is the fourth in a series of blog posts on St Helena, following my visit to the island in March 2018

Links:

- A complete set of photographs from my visit to St Helena can be found on my Flickr site. All of the photographs of the walk come from 18 March 2018, with the exception of the final photograph of Hutt’s Gate Store (taken a few days earlier).

- There is information on the Post Box Walks on the St Helena Tourism site

- For earlier thoughts on the art of walking, see my post on William Hazlitt’s essay ‘On Going a Journey’

- Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales site has a handy account of Edmund Halley’s expedition to St Helena and a summary of his discoveries