I went to St Helena, one of the remotest spots on the planet. I flew thousands miles to get there, travelling down a continent and then across an ocean. When there I met wonderful people, saw entrancing countryside, visited historic locations, scaled heights to enjoy exhilarating views. I spent two weeks in the most exotic location imaginable. And what, having travelled all that way after years of dreaming of getting there one day, was my favourite of all the places that I visited? The public library.

There are three libraries and one archive on St Helena, which is an impressive achievement for a place with a population of just 4,500. The library at the Prince Andrew School, named after St Helena historian Trevor Hearl, I have not seen. The government archive is located in the Castle, the un-castle-like buildings of officialdom in Jamestown, St Helena’s principal town. In the courtyard a modest doorway leads to a small reading area (two desks), a staff workroom, and the archives themselves next door. It holds papers going back 350 years relating to the East India Company and then British control, newspapers, military records, census returns and such like. It looks to be very professionally run, and though I saw nothing in the way of specialist storage facilities the archival documents all seemed to be in good condition. I browsed through newspapers from the 1920s (looking for cinema history nuggets) and greatly envied an archive where the staff can just step into the vaults next door and bring you what you want. By contrast, in London our newspapers are held hundreds of miles offsite and need to be fetched from their shelves in dedicated, humidity controlled, low temperature storage vaults in Yorkshire by robots,before being driven down to the capital, a process that takes two days. It’s efficient, and good for the newspapers, but oh so remote. Archives must have some romance about them, or else they become just a business.

There is a library in Plantation House, the eighteenth-century home of the island’s governor (currently Lisa Honan), located in the middle of the island in the bucolic St Paul’s area. It is famous for its giant tortoises (courtesy of the Seychelles), of whom the eldest, Jonathan (yes, he has his own Wikipedia page), is estimated to be around 186 years old. You can see him as part of the weekly Tuesday tours which include a guided visit to the building, including its library of some 2,000 books. On Wednesdays there are library visits alone available where you can browse the collection, with coffee and tea thrown in. The room in which the books are held is the very height of elegance, but the library itself for me was a disappointment. People like to hold and read the books because they are old, but old is not much of a virtue in itself. The books are humdrum stuff – army and navy lists, institutional histories, heavy memoirs, some obvious literary classics and some middle-brow literature from decades ago. Every volume proudly bears a Dewey decimal classification number on its spine, but it is not being added to as a collection beyond the occasional gift of a book about the island. For me, there was no life to it, and libraries should be the stuff of life.

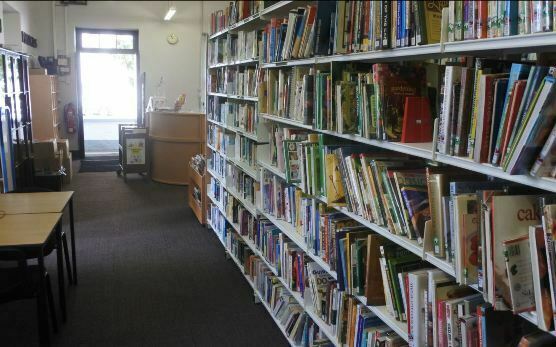

But then there was the public library. This is located near to the government offices in Jamestown, next to the pretty castle gardens. The guidebook is somewhat dismissive of this small space, saying of it that it is “supposedly the oldest [library] in the southern hemisphere … a reasonable if somewhat old-fashioned lending library”. Well, it may have been old-fashioned, but it delighted me. The building is small, with a main room holding fiction, children’s books and a specialist St Helena book collection in a locked glass cabinet, and an annexe at the back into which the non-fiction books have been tightly crammed. The issue desk is at the front. There is a side door which opens out onto the castle gardens, kept open on humid days. It does all the ordinary library things – lending, catering to local interests, organising reading events for schools, and so on.

So why did I like it so? I liked it first for its familiarity. The primary appeal of any library must be that it is like all the other libraries, offering you the same deal wherever you may find yourself. It’s a measure of civilisation, a gesture of welcome and understanding, a place and an arrangement which tell us that we have come home, wherever we might be.

Next, I liked it for the shelter. In hot weather, with the day’s walking done but some time left yet before sundown, the library was a place where I could rest and explore, without fear of interruption. It was a pleasant place in which to be. Moreover, it stayed open late on Saturday evenings, much as the town’s shops did, because the weekend is when the Saints come to town and party. So you drink, you dance, and you borrow a book while you’re about it.

But chiefly I liked it for the sense of a reflected world. Here, on a few shelves on a small island, hundreds of miles from anywhere else, was a distillation of what the world has to say about itself. The library told me where I belonged. Of course every phone purports to do this now, bringing us infinite knowledge possibilities at the tap of a finger. But – aside from the fact that mobile reception on St Helena is patchy and expensive – there is something irreplaceable about the sheer physicality of books on a shelf. The world is not shrunk to a small screen but laid out before you, selected and classified. It is the difference between an app and a map. One pinpoints where you are; the other makes you an explorer.

So it was that I sat down on the day that news came through of the death of Stephen Hawking, and read A Brief History of Time (the first few chapters) for the first time. What a marvellously clear and readable book it is, how special that I could find it to hand so readily, and how beautiful to the imagination it was to consider singularities and an expanding universe in so modest and remote a location. I was at the small end of the telescope, but able to see anywhere.

I dipped into the specialist collection of St Helena books, reading Beau Rowlands’ Fernao Lopes – A South Atlantic ‘Robinson Crusoe’ to learn about St Helena’s first resident. I read Primo Levi, George Orwell, a life of Edmund Halley, and a collection of essays on V.S. Naipaul. What was it doing there? There were no Naipaul novels in the fiction section. Maybe the librarian thought that Naipaul’s sharp analyses of Trinidadian society, subtly stratified by gradations of race and colour, echoed St Helena’s own mixed society, amiability itself on the surface but with who knows what tensions lingering beneath. As it is, the book had been borrowed three times (in twenty years). It was earning its place on the shelves.

I am not one of those who is sentimental, or passionate about public libraries. I have little sympathy for the arguments made by those such as Philip Pullman who argue vociferously against the closure of local libraries, blaming their disappearance on a barbarian officialdom or recalling the libraries of their youth and how important they were to their discovery of literature and culture. Times change, and the culture changes with them. The libraries are emptying, because they are losing meaning. The wistful child who wanders into a public library and discovers a world which sets them up for life has become a myth. I was that child once – it’s partly why the Jamestown library held such an appeal for me – but I wouldn’t make a universal truth out of it.

Some libraries will survive. National libraries and academic libraries will always answer a need, and have vast physical archives to maintain. But public libraries exist on a rotation of books of the moment. Many are attempting to change with the times, renaming themselves as ‘information hubs’ or whatever, filling their spaces with screens. Some do this quite successfully, showing how they have responded to changes in need and perception. But are they libraries any longer, or are they translating themselves into something else?

Public libraries will adapt to survive. They may change, move, or be absorbed by a different body. The public library of the traditional kind will wither away and die. I wish it were not so but I suspect that it will be so. And it occurred to me, as I sat in the Jamestown library reading of black holes and disappearing galaxies, that St Helena’s library could be the last of them. St Helena, like many island societies, is behind the times in many ways. Things come late to it (cars in 1929, television in 1995) and things take a long time to fade away. It has the air of a way of life that disappeared elsewhere decades ago – gentler, slower, less in thrall to time. That’s partly an illusion (the people of the island are well aware of the outside world, for good and bad), but it’s true that St Helena tends to hang on to that which is still working.

So I have this fantasy of a time, some years from now, when the public library, as a home for books, will have gone from across the world, bar this one small operation on a South Atlantic island. And people will journey far across continents and oceans, not just to see Napoleoniana, or fine countryside, or rare fauna, or bi-centenarian tortoises, but the last library, still providing welcome, shelter, and a map to the world beyond.

This is the fifth in a series of blog posts on St Helena, following my visit to the island in March 2018

Links:

- My photographs of the St Helena archives can be found on my St Helena Flickr album

- The British government recently convened a Libraries Taskforce with the aim of “helping to reinvigorate the public library service”

- So much for fantasy. There are plans for St Helena’s museum, archives and library to merge into a single cultural centre, plans for which can be found on the MWAI architects’ site.

Thanks for another fascinating blog. I am impressed by my local public library. As a user of their excellent home delivery service (monthly) I was invited to attend a well being afternoon there, and have just joined their Listening Group, for users of audio books.

Hi Linda. I am impressed by how well some local libraries in the UK are adapting to change, though I must admit it has been a long time since I felt the need to visit my own local library. I hadn’t heard of Listening Groups before now – a great idea.

The concept was new to me too. Free door to door transport is provided and tea/coffee and biscuits! I was also pleasantly surprised by the extent of the lending collection, including a decent range of DVDs. Remarkable given the financial cuts imposed in recent years. I remember too how well used the library in Willesden Green was before I moved up here – it was open and busy on Sundays.

I originally wrote that there were two libraries on the island, but John Turner of the St Helena Info site has kindly told me of the Trevor Hearl library at the Prince Andrew School. I have amended the post accordingly.

Dear Luke, many thanks for giving me and insight into the public library on St Helena as it is now. Things don’t seem to have changed much since I frequented it in the 70’s with my school friends nearly every afternoon

Hi Marilyn,

I expect things haven’t changed much with the library since the 70s, because they haven’t needed to. But change can be a good thing too, and the new cultural centre – if it comes off – looks impressive. I hope it attracts the next generation of children (and adults).