One of the things I was determined to do when visiting St Helena was to see a game of cricket. Though the island has a population of just 4,500, it supports eight teams who take part in a highly competitive league. It is an affiliate member of the International Cricket Council, and in 2012 took part in its first international contest, the the ICC Africa Division 3 T20 Tournament, where it came fifth out of eight, beating along the way Mali, Gambia, Cameroon and Morocco. Other international opportunities have been stymied by the cost and the remoteness of the island. The game has been played here since the 1840s at least, and is a part of the island’s identity. Inherited from the mother country, it exists for the love of the game, and in defiance of all the odds.

Cricket at St Helena is remarkable not just for its remoteness, but for the terrain. The island has almost no flat country. Everything is uphill, or downhill, usually steeply so. Apart from the airport, for which land had to be flattened to accommodate the airstrip, the only piece of ground of any size that is roughly flat and horizontal is to be found on top of a 300-foot rockface, to one side of which is the picturesque Heart-Shaped Waterfall (dry most of the year, including when I visited). This patch of ground, next to the island’s secondary school, Prince Andrew School, is for six months of the year the island’s cricket pitch, and for the other six months its football pitch.

As cricket grounds go, Francis Plain is spectacularly located, but falls a little short of first class conditions. It is noticeably uneven and pitted, therefore favouring boundaries over the scoring or ones and twos, I would suspect. I climbed to the ground via High Knoll Fort (the derelict fortress that towers over the north side of the ground) and found myself watching a 20-20 match between a team in red and a team in green, later learning that these were Jamestown and Longwood respectively.

It wasn’t conspicuously great cricket, but it was engrossing. Longwood were in the field, and I was much taken with the looping spin bowling of David George, who gave the ball so much air it seemed ripe for being sent far over the boundary every time. But the Jamestown batsmen treated him with noticeable respect, and the sharp wicketkeeper Darrel Leo made two stumpings. Jamestown nevertheless went on to win by eleven runs (though I had left before the game ended). It was a satisfying contest to watch, though there were probably only three or four of us doing so who weren’t members of one or other of the sides playing. The sun shone brightly, the rain that comes and goes so quickly on the island held off for the duration, while the backdrop of hillside and ocean beyond could not be bettered. It was epic and intimate at the same time – small figures on a patch of green, playing out an eternal contest, high on a plateau beyond which, just out of sight, the land fell away with dramatic suddenness.

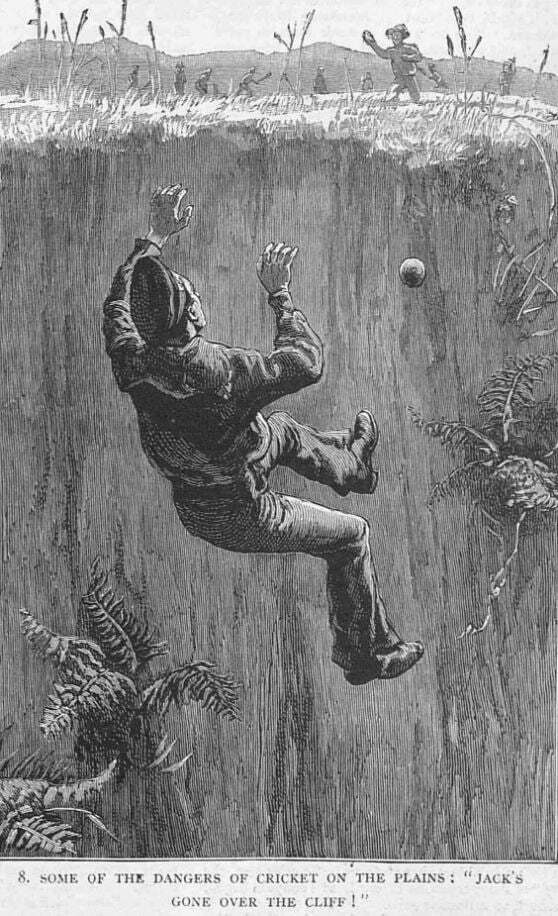

Perhaps the only thing known about the game on St Helena, that is among enthusiasts of cricket trivia, is that during a game a player once fell over a cliff edge to his death. The Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack for 2012 recounts, “according to local folklore – supported by reports found in a private archive – a slave called Jack fell off a cliff to his death while taking a catch on the boundary in 1886”. So what’s the truth behind this? If you visit St Helena, you can well believe the stories of people falling to their deaths. The number of vertiginous drops down rocky cliffs even from public paths is considerable. There are tales of soldiers on sentry duty during the time of Napoleon’s incarceration being blown off cliff edges by the gusts of wind that plague parts of the island. In the south west of St Helena, Man and Horse Cliff is supposedly so named because a man and his horse failed to stop at that very spot.

But did anyone actually fall off while playing a game of cricket? After a bit of a rummage through the newspaper archives, I find that the source of the story is not a private archive but the British illustrated newspaper The Graphic. In its issue for 20 February 1886 there is a short article entitled ‘A Visit to St Helena’, reporting on a trip to the island in July 1885. At the end of the piece is this:

The cricket-ground, on a part called Salisbury Plain, is very dangerous for out-fielding, and the pitch is very bumpy. One poor Jack Tar lost his life while playing. He got up too much steam in running after a ball to long-leg, could not stop himself, and went over the precipice, a sheer drop of sixty feet.

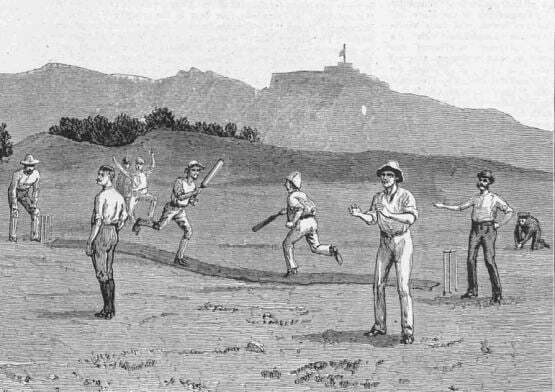

So, he was a sailor (Jack Tar), not a slave (of which there were none by the 1880s), who met his death some time before 1885. Newspaper reports show that the garrison at St Helena often played cricket matches against teams made from the crews of passing ships, therefore it is credible that he was sailor – and someone unfamiliar with the geography. There is no Salisbury Plain on St Helena, but from the illustrations provided in the paper (derived from sketches by a Royal Artillery captain E.A. Smith) the ground on which cricket was played was Francis Plain, the same as it is today, with High Knoll Fort high in the distance. The illustrations include a dramatic recreation of ‘Jack’ going over the edge, and an equally speculative recreation of his body being carried down a path which is recognisably that which leads down the cliff face from Francis Plain to Briars Village below.

The problem is that the Francis Plain cricket ground does not end with a cliff edge. As the photograph at the top of this post shows, there is a gentle incline of fifty yards or more leading from one quadrant, which is then followed by the steep drop into the valley below. Even if the ground were larger in the nineteenth century than it is today, with some of the present vegetation removed, the fielder would have had to have run considerably beyond the edge of the boundary to have reached the precipice. If he had done so, the drop would then have been not 60 feet but 300 feet or more.

It’s not possible to tell from the available evidence whether the story is based on an actual death – maybe from a player who wandered too far in search of a lost ball – or was spun out of jokes made about the ground’s location and the island’s dangerous reputation. Maybe there is a reference someone in naval records (assuming the victim was a sailor), which might record a death by falling while a game of cricket was being played. I doubt it somehow. But let’s not have any truth get in the way of what is a great tall story.

It is a curious but refreshing experience to watch a cricket match where you do not know who is playing. You have nothing to follow but patterns. Cricket has this iconographic quality which perhaps no other sports possesses to quite such a degree. It is figures in a landscape engaged in a contest, in which they are both a part of that landscape yet offset by it. From a distance they are engaged in a time-honoured ritual, whose outcome matters not, with only the fact that the play continues being of significance. Close up, and it is a proper contest, side against side and individual against individual, playing out the profound permutations of the game.

Perhaps this is why cricket has generated so much art, probably more than any other sport. Maybe athletics can compare, if one considers Ancient Greek pottery, but there the focus is on the individual. It is not so much the sport that is celebrated as the kind of the person who excelled in it. In the art of cricket, the individual is only one figure amongst several in a landscape; people arranged in space, patterned according to the rules of the game.

Little of it is great art, but even the worst of it is a response to that immediate visual appeal. Maybe it is because there is no stadium – at least at the village cricket level, which is what was on show at St Helena. It is both a special event taking place within specific parameters, and yet something that could be taking place on any flat piece of greenery. It is a performance, even a kind of dance. There is such a benign, satisfying, natural quality about it. It has the great pull of recognition. It makes anywhere home, even a rock in the middle of an ocean, with just the one field on which to play out the game, now and always.

This is the second in a series of blog posts on St Helena, following my visit to the island in March 2018

Links:

- The Graphic is available on the British Newspaper Archive (a subscription site)

- There is a short account of the game and its history on St Helena on the International Cricket Council website

- The St Helena Cricket Association’s Facebook page needs updating, but it has some great photographs

- The St Helena Online news site has several reports on the St Helena team’s success in 2012

Delightful, gently discursively post, as always. Reminds me that cricket is so much nicer to read about, in seasoned hands, that to watch – or play.

Thank you Ian. I was going to throw in a reference to Steve Smith and ball tampering, but decided it wasn’t needed. Cricket writing (from which I must exclude my efforts) tends to be much better than cricket art. The best of it can be better than the game itself, but that’s because its finest practitioners (John Arlott, CLR James) could see that much more.

Alas, I never could play the game at all. But I seldom tire of watching it.