None of us entirely likes the stories others tell of us. The pleasure of acknowledgment is countered by the failure of comprehension. No one ever quite gets us right. This is notably true of St Helena. Aside from the misrepresentation of the far-away island by tourists such as myself, with quick opinions based on fleeting visits, its most notable story – the one everyone knows if they know anything about St Helena – is that Napoleon was imprisoned there following his defeat at Waterloo. For many, this is the island’s first and only story.

If you visit St Helena, you soon see how misleading this is. Napoleon was held on the island from 1815 until his death in 1821, spending most of that time in a house at Longwood, on the scrubby, windblown east of the island. Longwood House exists as a tourist attraction, as do other Napoleonic sites, such as his original tomb location, the Briars pavilion where he spent his early weeks on the island, and assorted fortifications manned by a British garrison determined to thwart any attempt at escape. But Napoleon was not a part of St Helena. He was an alien. He has remained so ever since – obviously an important part of the history, but something implanted rather than something that grew there. The Saints today must perforce live with the legend, but Napoleon is in no way fundamental to the island’s identity.

Yet the fiction films made about St Helena almost all focus on this alien narrative. In visiting the island I was bound to consider its film history, and it is an interesting one. Films were shown there in makeshift cinemas from 1914, with sound introduced only in 1940. A number of cinemas or cinema halls sprung up over the post-war years, and on an island where one in two people has a car (essential for a place so replete with steep hills), it is perhaps not surprising that they even had a drive-in cinema in the 1970s. The last cinema closed in 1988 (television finally reached the island in 1995). Now there is only Brown’s Video Library in Jamestown, still offering VHS tapes in faded sleeves.

The earliest film taken in St Helena that I can trace dates from 1924, a now lost Fox News newsreel showing sailors visiting the island. A more substantial film was made in 1925, when the then Prince of Wales visited as part of his world tour. A film record, entitled Official Record of the Tour of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, was made by British Instructional Films. The film does not survive in a complete state, but scenes of the island are among the parts that do – they include the castle, Jamestown, Jacob’s Ladder, Longwood House, and Napoleon’s tomb. To judge from a frame still in the Jamestown museum, home movies exist from 1929 at least. Thereafter assorted documentaries have been made on and about St Helena, mostly travelogues stressing its exoticism and remoteness.

Just the one fiction film has been made on St Helena, and that for only a few short scenes. But several have been made that depict the island in an imaginary way. Of these, only one is not about Napoleon, and it really only alludes to St Helena. That film is Slave Ship (USA 1937), an historical drama starring Warner Baxter, Wallace Beery and Mickey Rooney, about a ship’s captain who tries to break way from the slave business to more honourable work, but has to face up to resistance from the crew. Slaves are seen escaping from the ship when it nears St Helena, and there is on-board court martial with British officials from the island, but no scene features the island itself.

There have been many, many Napoleon films that refer to St Helena, sometimes with a death-bed scene, too many to try and list here. Only a few feature St Helena as the primary location, and it is these that I want to focus on. Most show the history not as it was but as it might have been, as the filmmakers fight contend between reality and romance, seeking their own ways of escape from history’s island on which they find themselves.

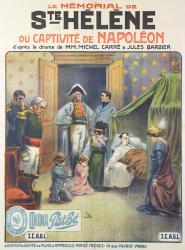

To begin with, there were a remarkable three St Helenian titles made in 1911-12, when fiction films were short and silent. The two-reeler Mémoires de St. Hélène aka Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène (France 1911) establishes the standard tropes: Napoleon surrounded by his acolytes, befriended by the British family the Balcombes (whose 13-year-old daughter Betsy enjoyed a happy friendship with Napoleon), only for the governor Hudson Lowe to crush his spirit through petty adherence to the rules. Napoleon then dies, mourned by all. It is the story burnished by the memoirs of the time, notably those of Napoleon’s Irish surgeon Barry O’Meara and Emmanuel, comte de Las Cases (whose memoir gives the film its title). Most fictional version of the events have stayed close to this interpretation ever since (I myself have a sneaking sympathy for the demonised Hudson Lowe, who curtailed Napoleon’s attempts to charm his way into a comfier captivity in England effectively, and later was instrumental in abolishing slavery on the island).

In Mémoires de St. Hélène, therefore, the great Napoleon (played by one Laroche) is brought to St Helena, where he is made welcome by the Balcombe family. But a new British governor, Hudson Lowe (played by Georges Tréville), has Napoleon moved to Longwood, where Napoleon suffers from assorted petty restrictions. The film heads off into imaginative realms when Napoleon ends up saving Lowe’s life, then makes an escape attempt from the island. The film ends with the death of Napoleon and Lowe terrorised by his ghost. It survives in the archives of the British Film Institute.

Only the titles survive of a film made the same year, Napoleone a Sant’Elena (Italy 1911), which showed Napoleon dreaming of his past triumphs while imprisoned on the island, a handy device for getting around the lack of inherent drama in the actual imprisonment. The following year, America chipped in with Prisoner of War (USA 1912), with Charles Sutton playing Napoleon. This shows Napoleon making a bitter farewell to France before sailing to St Helena, where he is housed at Longwood where he quarrels with Hudson Lowe, chafing at the restrictions put upon him. He dies on a dark and stormy night. (Again, the film is held by the BFI).

The first feature length film on the subject has an interesting history behind it. The French director Abel Gance had planned a six-film series of feature films about Napoleon, in an act of grandiose cinematic ambition worthy of the subject he worshipped. In the end Gance was able to make just the first of these, the five-and-a-half hour epic Napoleon (France 1927). But his scenario for the sixth part was taken on by the director Lupu Pick and made in Germany as Napoleon auf St. Helena (GE 1929). Starring the great Werner Krauss as an authentically tubby Napoleon, the film was well enough received at the time but is little known now. A copy survives at the Deutsches Kinemathek, and it was previously released on VHS (though not on DVD). Film historian Christine Leteux reports that it is “rather solid, stagey and static”, but conveys well the atmosphere of the confinement at Longwood house, with a notably fine performance from Albert Basserman as the paranoid Hudson Lowe.

The film does have some location shots on St Helena, filmed by a second unit sent out specifically for the purpose. The scenes include a long shot of the island, waves crashing on the Jamestown shoreline, Longwood House, a gun emplacement, and the site of Napoleon’s original tomb. But more than just location shots, the film shows sentries on duty outside Longwood House and manning the heights, and in one sequence a go-between is handed a secret message inside Longwood House (studio setting), walks past the guards outside the building (island setting – presumably a different actor), and passes on the message to another at Jamestown (studio setting). For these brief moments the real St Helena became the imagined St Helena.

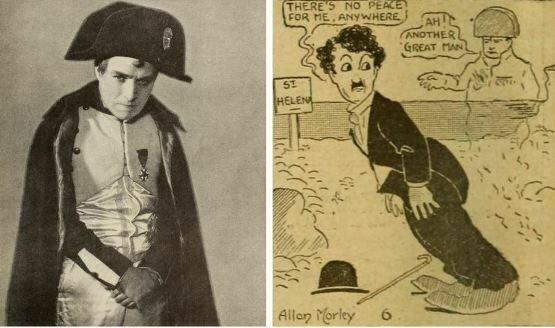

What would have been the most notable of St Helenian Napoleon films was never made. In the late 1920s Charlie Chaplin became obsessed with making a film about Napoleon. As Chaplin’s biographer David Robinson observes, “Napoleon offers a uniquely rich role for an actor of small stature.” In 1933 Chaplin met up with the British writer, and future radio broadcasting great, Alistair Cooke, who researched a script for him based on Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène by Las Cases, one of the retinue of French followers who served Napoleon on the island. Chaplin rejected the idea, or at least the script, but evidently remained intrigued by the St Helena theme. Over 1935-36 he worked on another script with British left-wing intellectual John Strachey, under the title Napoleon’s Return from St Helena, which used ideas from a novel by Jean Weber, La Vie Secrete de Napoleon 1er, in which the emperor escapes from St Helena thanks to a double who took his place on the island – a persistent myth ever since Napoleon’s death. For whatever reason, plans for the film went no further. A draft of the script survives, however, and a few tantalising photographs of Chaplin in character. Ah, what might been. Instead, of course, Chaplin, instead made a film about another tyrant, The Great Dictator.

The substitution fantasy has been filmed twice, however. It was first expressed in the MGM short film Man on the Rock (USA 1938). This was a dramatised documentary which posed the question whether it was Napoleon or a double who died on St Helena. Edward Raquello played Napoleon in what was a popular short subject in its day which enjoyed a long afterlife distributed through educational film libraries.

The theme gained renewed recognition following the publication of Simon Leys’ 1986 novel, La Mort de Napoleon, which has Napoleon swap identities with a lookalike, Eugène Lenormand, only to find his escape to France beset by problems which lead him to question the nature of his identity. This was adapted as the slight but rather charming The Emperor’s New Clothes (UK 2001), with Ian Holm as a puckish though too elderly Napoleon and his double, while Malta serves for the St Helena locations. The film mostly follows Napoleon’s misadventures in Belgium and France, but does have fun with his slobbish double, who enjoys having Napoleon’s acolytes on St Helena obliged to treat him with high respect, as he increasingly gets imperial ideas of his own. Then he falls dead, and the real Napoleon finds as a consequence that his plans have crumbled (a plot twist that Chaplin had also planned). Now he can only be the humble nobody he has been pretending to be. The film concludes memorably with Napoleon confronted by the inmates of a lunatic asylum, all of whom believe themselves to be him.

Just as three films were made about Napoleon on St Helena in 1911-12, so three productions appeared over 2001-03. Following close on the heels of The Emperor’s New Clothes was a 2002 French mini-series made for television, Napoleon. This uses the device of opening on St Helena in 1816 with Napoleon speaking to Betsy Balcombe, recalling the great events of his life, with the story then unfolding in flashbacks (Christian Clavier plays Napoleon, David Francis plays Hudson Lowe). The feature film Monsieur N. (France 2003), directed by Antoine de Caunes, is a very handsome production, whose painstaking recreation of the St Helena of the 1810s (filmed in South Africa) would probably be pleasing to the Saints (as the locals are called). It gets across the isolation, the vertiginousness, and the spartan conditions, as well as showing something of mixed races that made up the general population. Featuring a dour Napoleon from Philippe Torreton and eye-popping villainy from Richard E. Grant as Hudson Lowe, it begins by keeping close to history but then turns into a convoluted whodunnit, involving arsenic poisoning, body substitution, a foiled rescue attempt and the possibility of Napoleon living out his days peacefully in Louisiana with Betsy Balcombe.

I can find little information in English on the Franco-Polish production Jeniec Europy / The Hostage of Europe (1989), directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, but it is a St Helenian narrative based on a novel by Juliusz Dankowski, with Roland Blanche as Napoleon and Vernon Dobtcheff as Hudson Lowe. It seems to have presented the history without imaginative embellishments [see comments]. Orson Welles must have had fun playing Lowe in Sacha Guitry’s biopic Napoléon (France 1955). The three French films made of L’Agonie des Aigles, in 1922, 1933 and 1952 have each had scenes on the island. And there are more such cameos.

The key St Helenian feature film, however, was made in 1972. Flawed as it is, Eagle in a Cage (UK/USA 1972), is the most effective in capturing the sense of claustrophobia, shrinking possibilities, and interlocking characters playing out a game that only those beyond the small island on which they find themselves can ever win.

Eagle in a Cage was developed out of a 1965 American television play, starring Trevor Howard as Napoleon and produced as part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame series (there had been an earlier Napoleonic TV production, St Helena, based on a 1936 Broadway play, shown in the USA in 1949). Its writer Millard Lampell won an Emmy for his script. He was an interesting character, who started out as a folksinger, teaming up with Peter Seeger and Woody Guthrie, before becoming a scriptwriter for film and television. A committed radical, his refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee led to him being blacklisted for while, forced into writing scripts under pseudonyms. Eagle in a Cage, the TV production, was scripted in his name, however, and on the strength of its success a feature film was eventually produced, with Fielder Cook directing.

Watching Eagle in a Cage is a curious experience. It is not helped by the dreadful quality of the print from which the DVD copy has been made, a print which is also the source of copies of the film to be found on the Internet Archive and YouTube (it seems the film was never copyrighted, which is why it can be so readily found online). But even were the print pristine, the halting, uncertain directorial style, the austere music, and the alien terrain would still combine to give the film as distant, unsettling feel. It was shot in Yugoslavia, near Split, and the white, rocky landscapes look nothing like St Helena, though the looming crags do get over the sense of the landscape as fortress.

What makes Eagle in a Cage a pleasure is some of the performances. Lampell’s clever (sometimes too clever) script attracted a remarkable cast. The late Kenneth Haigh is a fine Napoleon: alert, inquisitive, playful; a step ahead of (almost) everyone in his thoughts, not in least bowed down by his circumstances. Michael Williams is excellent as Napoleon’s surgeon, Barry O’Meara, the film’s conscience until his failure to convert ideas in action is exposed at the end. Billie Whitelaw gets top billing as Napoleon’s disillusioned mistress, Madame Bertrand (in reality his island mistress is said to have been Albine de Montholon). Ralph Richardson discovers just the right balance between pomposity, calculation and bitterness as Hudson Lowe, a man thwarted throughout his professional career who now has the grand opportunity to prove himself. But his pretensions are snuffed out by the late appearance of his better, and Napoleon’s intellectual match, the fictional Lord Sissal, played by John Gielgud.

This barnstorming cameo may be one of the best screen performances of Gielgud’s career. Imperious, lecherous, devious, contemptuous of all time-servers, his character is a British government figure who has come to make Napoleon a deal. In the film’s boldest piece of historical invention, Sissal offers to help Napoleon to escape to France, where he would suppress revolutionary elements and then declare war on Prussia, leading to a balance of political power that would be of advantage to Britain. If not, Napoleon will go on trial, for “crimes against humanity” (a decidedly a-historical use of a twentieth-century term). Napoleon agrees, but the plan comes to nothing when Napoleon falls ill from the stomach ulcer which has been building up throughout the film. He will never escape from St Helena.

There are some oddities, including the casting of black actor Moses Gunn as Napoleon’s familiar, General Gourgaud, a sexual relationship between Napoleon and Betsy Balcombe, and a silly escape attempt thwarted on the shoreline. Some of the minor roles are weak, and Lampell has his characters all speak far too intellectually, which only adds to the unreality of film. Its strangeness is its virtue, and its downfall.

Eagle in a Cage in full

What makes Eagle in a Cage work, in its odd way, is that it is a fine example of an overlooked genre, the island movie. There are many examples: Robinson Crusoe (the Buñuel version for preference), Lord of the Flies, The Edge of the World, The Wicker Man, Jaws, I Know Where I’m Going, Moonrise Kingdom. There seem to be three kinds of island movie: the Crusoe (Cast Away), the place of fantasy or peril (King Kong) and the micro-society. In the latter we see a society confined by its geography, which acts as though it has self-determination but is in fact wholly dependent on forces that lie beyond its shores. It is outsiders whose discovery of the island shapes the narrative: sometimes being changed by the experience, but more often being the agents of changes themselves.

Such a scenario might apply to any small society, but the crucial feature of the island movie is that you have to see the sea. It physically defines the limits of your aspirations. This Eagle in a Cage does well, for all that some of its mountainous landscape shots are too vasty for small St Helena. It not only regularly reminds us of being constrained by the ocean, but in the battle of wits between Napoleon and Sissal we see how the island dynamic plays out. Sissal holds the strings; he represents land and power, and because he does so he makes Napoleon do his bidding. Even if Napoleon hopes to become his own man once again if the British plan comes off, he has been forced into concession. He is no longer the person he once was, that his followers still believe him to be. His sickness is a manifestation of his moral failure.

The film stories of Napoleon on St Helena have all struggled because the narrative is elsewhere. St Helena was a final act, but we want to know what the action was that led to this curious collection of people coming together in the middle of an ocean. Yet filmmakers keep coming back to this picture of greatness reduced to absurdity. Their weakness has been a taste for historical what-might-have-beens. They are more successful where they allow space for the interplay of character and politics to be worked out, and where they give us a sense of the island – as metaphor and hard reality. The leading player in a St Helena movie should always be St Helena.

This is the third in a series of blog posts on St Helena, following my visit to the island in March 2018

Links:

- The St Helena Island Info site has a page on the history of cinemas on the island

- Eagle in a Cage can be seen on the Internet Archive and on YouTube

- The AFI Catalog has a useful background history for Eagle in a Cage

- The Fondation Napoleon’s site has some good descriptions of Napoleon and Napoleonic era films in its On Screen section, if you can work your way through a rather unhelpful presentation of the data

On my Picturegoing site I have reproduced an account of going to the cinema on St Helena in 1929 http://picturegoing.com/?p=5287

Christine Leteux, the film historian mentioned in this post, has pointed out to me a version of the 1929 German film Napoleon auf St Helena can be found on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ssZUk6CQVCI

It’s a reissue version of the film, with over 30 minutes cut from the original, a commentary, and some voicing of the actors’ parts. I wrote originally in this post that though this film had some location scenes on St Helena, they were probably re-used from earlier newsreel footage. Having now seen the film, it is obvious that a second unit was sent out to film scenes there, bringing back not only location scenes (Longwood House, Napoleon’s tomb)but shots featuring sentries, one of which is a piece of dramatic business intercut with studio action. I have rewritten parts of my post accordingly.

These are some images from the film that were taken on St Helena:

Sentries outside Longwood House

Soldier above valley

Flags and soldiers outside Longwood House

The secret messenger speaks to sentries outside Longwood House

Napoleon’s original tomb on St Helena

I have now seen Jeniec Europy / L’Otage d l’Europe / The Hostage of Europe (1989), as the film has appeared on Daily Motion – part 1 https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6zdtkm and part 2 https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6zds5y, ripped from the Polish DVD. The dialogue is in French and English, though there is not too much of the latter as the English characters oblige Napoleon and his entourage by speaking French. There are Polish subtitles. The film is a talky psychodrama between Napoleon and Lowe, with no reference to the Balcombes. It was shot in Poland, Bulgaria, France and the USSR. It is stylishly constumed, and the exterior Longwood, where Napoleon stayed, is accurately portrayed. The film ends with Napoleon’s death and Lowe admitting defeat.

Here are some screengrabs:

Roland Blanche as Napoleon

Napoleon dying

Roland Blanche as Napoleon, Vernon Dobtcheff as Hudson Lowe (the smiles are misleading)

Longwood in the rain