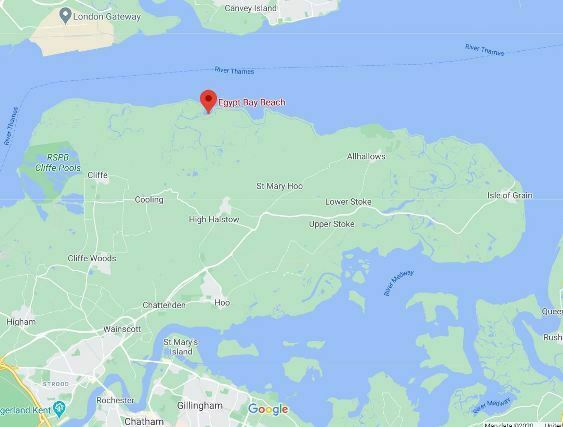

Some places have so little to tell about themselves, and that can be part of their appeal. Take Egypt Bay, for example. It’s a small bay on the northern coast of the Hoo Peninsula, that overlooked piece of land jutting out of the Kent mainland, caught between Essex and Sheppey. The River Thames flows by at its widest, in the act of turning into the sea.

The peninsula is a flat territory of reclaimed marshes, farmland, occasional villages and some light and heavy industry on its eastern fringe. Located in the middle of the populous south east of England, it is extraordinarily empty. It is a forgotten space, where few live and few travellers venture, lacking as it does apparently any significant features. There are some attractive spots – the High Halstow nature reserve in the centre, on the one high piece of land; the quaint village of Cliffe, with its charming pools, which only once you are close reveal by the smell that they are used to treat sewage; and the seemingly misplaced castle at Cooling (home once to Sir John Oldcastle, unwitting model for Falstaff, and now home to the musician Jools Holland), defending a land no one would ever think to invade.

The chief attraction of the place lies in its absences. It is a place for long walks through fields and along the almost featureless coastline. Here one walks simply because one has to walk.

If you go to the High Halstow Nature Reserve, having taken in the epic view across the Cooling Marshes to the west, follow the road and then path northwards for a couple of miles, past Decoy Farm, over a couple of gates that seem locked for no reason, up a rise in the land where a sea defence has been built, and there you are – at Egypt Bay.

The hardy few who make their way here, drawn by the exotic name, may be understandably disappointed. It’s a scrappy place. There is a small curve of shingle to the right-hand side of the bay, a mockery of a beach. Thereafter there are muddy pools, clumpy marshes and a hard sea wall on the western side. Some wading birds forage in the mud flats. Bits of plastic rubbish flutter in the breeze. Beyond, the Thames flows sluggishly by, while in the distance, on the Essex coast, lies London Gateway container terminal and Canvey Island. Who would want to travel here?

Well, I do. I am fond of Egypt Bay. I am fond of the thrilling, stark coastline walk to the east, with the Decoy Fleet (a saline waterway) running parallel to the coastline, and – on a clear day – glorious skyscapes to lift the heart and make the wanderer feel that there could be no better place to be.

Egypt Bay itself looks undistinguished, but if you do not want simply to sit there and contemplate nothingness, you can always wonder about the name. What brought such unwarranted exoticism here? Egypt Bay as a name dates back to the early 1800s at least (it turns up in newspaper references) and probably was established in the eighteenth-century, though no map of the area from that time that I can find names it. Undoubtedly its name derives from what was the nearby Egypt Marsh Farm (the exact location of which seems to be unknown), which will also have provided what was once the name for the marshland surrounding the bay, Egypt Saltings. This part of the peninsula was reclaimed around the 1630s, and maybe it was then that the term ‘Egypt’ was first used. It could have been a corruption of an owner’s name, or a reflection of some interest of theirs. Perhaps it was biblically inspired. We may never know. (There are extant former farm buildings named Egypt elsewhere in Kent – one at Hadlow, near Tonbridge, dating from the 16th century, another dating pre-1800 at Brenchley, near Tunbridge Wells.)

One should not think of a regular farm, however. A solitary building with overseer, with the owner safely back in the mainland towns of Chatham, Rochester or Strood is most likely. The Hoo marshlands were malarial. Few could live there, and the few obliged to work there would not have lived long. It was wretched territory, well into the nineteenth century, when the bay was a landing point for smugglers and in the 1860s a coastguard hulk was stationed offshore. Such a hulk may have been seen by Charles Dickens, who walked these lands and weaved them into Great Expectations (published 1860). A set of gravestones at St James’s church in Cooling is said to have inspired the opening scene of the novel; the bleak marshlands to the west of Egypt Bay were reworked as those over which Magwitch and Compeyson escaped; and a hulk at Egypt Bay itself could have represented that from which the men escaped, though Egypt Bay itself was never home to convict hulks (they were located next to St Mary’s Island, north of Chatham). Great drama can come even from the edge of nowhere.

I have been reading Charles Darwin’s Journal of Researches, originally published in 1839 as Journal and Remarks, and now better known as The Voyage of the Beagle. It’s Darwin’s account of a three-year expedition through South America, the Galapagos islands and Australasia, the experience of which helped develop his theories of evolution. (Intriguingly, the Beagle ended its days in the 1840s as a coastguard vessel, moored off the Essex coast on the other side of the Thames to Egypt Bay).

Darwin was a singularly accomplished writer, employing compelling prose to express precisely what he thought and saw. In doing so he made his readers sensitive to the unconsidered forces that govern things with the force of religious revelation. He analyses geological and animal phenomena with absolute precision, deducing the workings of time in even the most unpromising of landscapes. He saw something in everything. It is perhaps because of this extraordinary facility that he experienced a special delight in a landscape that offered nothing. In the middle of the bleak plains of Patagonia, he comes up with these words on such emptiness:

All was stillness and desolation. Yet in passing over these scenes, without one bright object near, an ill-defined but strong sense of pleasure is vividly excited. One asks how many ages the plain had thus lasted, and how many more it was doomed thus to continue.

To delight in such absence is a special gift, or rather to be able to articulate it so. I suspect, or at least hope, that there is something in all of us that treasures desolate places. They bring home to us the slow workings of time, and our helplessness in the face of this. And, yes, something within us finds this strangely pleasurable.

Egypt Bay is not an absolutely desolate place. It has its occasional visitors – hardy walkers, cyclists, occasional families lured by the false promise of a beach.

Pure desolation has a kind of magnificence about it. A place like Egypt Bay is more the product of neglect. It is a place of forgetfulness, beyond the edge of where we think about things. A purely desolate place would not have scraps of rubbish or the air of half-heartedness about it. A Roman urn was found here; for hundreds of years people have come to this edge of things and wondered how had they fallen into such insignificance.

Wandering along the sliver of a beach I spotted something in the fine shingle. It was a Costa coffee cup lid. One sees plenty of these discarded in all kinds of places, but this one was different. It had been weathered to grey. It looked like an old thing. It was half-buried in the shingle, in the process of being swallowed up by history, to be dug up again centuries later by some future archaeologist. Handling it with the greatest care, they will identify it and classify it. It will be given a label and placed in a museum.

The label will say that such coffee cup lids are common – we future museum visitors know this, we see so many of them, so hard to distinguish from those of Starbucks, Caffè Nero and those other classic artefacts of early twenty-first century times – but will draw our attention to its particular qualities. Look again, it will say. This coffee cup lid has so much to tell us. It is the perfect indicator of the throwaway society that created it. Its very existence reveals so much about the socio-economics of its time. We have found similar objects at sites across the globe, indicators of a common culture become part of local custom. This particular lid is unusual for having been found in an unfrequented corner of the country, where people had no reason to be. This makes it mysterious.

When so much has been lost from a civilisation that left little behind it except for those barely decipherable digital archives that survived the great crash, these precious objects connect a strange people to the everyday. From this we may try to understand them, in a limited way. How ironic, from what we can deduce of what can still be read of those digital archives, that they so regretted the plastic which they created in vast amounts then threw away, yet it is almost all that survives of them.

Think of one of those people, wandering alone on the fringes of a society, resting for a while at what was once a bay but long ago was reclaimed by the rising seas. They carried their cup with them to this far corner, from which we may reasonably infer the special significance of drink, cup and the lid that protected it. They left cup (we assume) and lid behind them, whether by accident or by local ritual whose purpose is now lost to us, we do not know. We can see them sitting on the shore, drink in hand, looking out to sea, perhaps dimly aware of their fate. Let us try hard to imagine them.

We call them the Lid People. They may have numbered in the millions. But we must move to the next room and the people of the mid-millennium. They have so much more to tell us.

Links:

- The Kent County Council database Exploring Kent’s Past has information on archaeological sites in the county, including the slim findings at Egypt Bay and records of Egypt Marshes Farm and the other Egypt farms

- English Heritage has published online research reports assessing the historic areas of the Hoo Peninsula. High Halstow, Hoo Peninsula, Kent, and St Mary Hoo, Hoo Peninsula, Kent, both by Joanna Smith and Jonathan Clarke, and a summary report Hoo Peninsula, Kent: Hoo Peninsula Historic Landscape Project, were helpful in aiding the historical side of this post

- JSBlog – Journal of a Southern Bookreader, written by Ray Givran, has a fine post on the 1951 novel by Howard Clewes, The Long Memory, which is set among the Thames marshes (it was turned into an excellent 1953 British film of the same title, directed by Robert Hamer). Clewes describes the Hoo marshes with care, including a ‘Morocco Bay’ (“a sad, forgotten place”) that is clearly Egypt Bay

Fascinating! Wonderful pics. Christine

The Hoo Peninsula is a gift for an average photographer. All those flat lands and vast skies. Here’s my Hoo photograph album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/33718942@N07/albums/72157715248822088

I had never heard of Egypt Bay. Thanks to your photos and eloquent description I now feel that I know it!

Thank you Linda. It’s probably as much a place of the imagination as it is a small spot on the map.

Interesting that you call this area ‘a place of the imagination’. I very much agree. I’m currently working on a PhD/novel based on my experience of walking the Hoo Peninsula – particularly the area from Gravesend to Cliffe. I loved your expression ‘it is a place of forgetfulness, beyond the edge of where we think about things’ as this is exactly why I am interested in writing about it, to explore this edge, as it were.

Curiously, I remember you from the BFI many years back. I worked in BFI Video (later DVD Publishing) with Erich for many years!

Hello Caroline, I do remember you, faintly (the memory is faint for so many things these days). How curious that the four people in these comments on a piece about Kentish geography should all be ex-BFI employees.

Anyway, I’m glad you like the piece, and the territory, which I visited again only the other day. Best of luck with the PhD/novel (an interesting combination). I’m rather struck by those words “it is a place of forgetfulness, beyond the edge of where we think about things” because I don’t remember writing them, and yet there they are. And they seem true.

Last night l slept at Egypt bay in the morning I took a dip in the water

My, that’s quite something. You certainly picked the right night for it, given this weather.

Fascinating. I have taken to cycling out along the Thames path between Cliffe Pools and Allhallows lately, the peace and quiet is the perfect antidote to all that has gone on lately and working from home. I am taking a camera with me to try and help identify some birds of prey I keep seeing, I know there are buzzard and kestrel but I am sure there is something else too.

I hadn’t spotted birds of prey there before now. Time to go back.

I loved reading this. Having been brought up on Sheppey, I found your writing most evocative of an area I remember; barren and fecund at the same time.

Another connection with Egypt Bay is that it is where Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. lost his life in September 1946 whilst test-piloting the experimental jet made by his father’s company and known unofficially as the Swallow. The wreckage was found in the bay and his body in Whitstable (apologies for this gruesome detail, but the distinctly separate locations tell their own important tale).

Thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed reading it. I like those words “barren and fecund”.

I only found out after writing the piece about the de Havilland connection and must explore it further (as I was brought up in Whitstable there would be extra resonance for me).

A piece I wrote earlier this year covers another connection of sorts, that of the filming of David Lean’s Great Expectations, though they filmed at the next door St Mary’s Bay, and don’t seem to have used Egypt Bay itself – https://lukemckernan.com/2022/01/12/pip-lean-and-cinderellla/.

And there’s this on Sheppey: https://lukemckernan.com/2019/04/16/scully-turner-and-sheerness/. What a rich area the North Kent coast is.

I’m glad you mentioned Howard Clewes’ novel ‘The Long Memory’. I first read this some thirty thirty years ago and it made a powerful impression on me then (as did the subsequent film) and I have re-read it several times since. Clewes; wonderfully evocative descriptive powers of the lonely marshland around ‘Morocco Bay’-in reality Egypt Bay- chime with my own experience when I followed much the same route as you describe to Egypt Bay. It is indeed a magic place where you can be at one with nature between sea and sky with nothing but the wind,the wading birds and the distant pasisasing the ships in the estuary and the whispering creeks and inlets of the marshes

.One can easily imagine Clewes’ wronged hero Philp Davidson taking refuge in the hulk of a Thames barge in the bay after serving a wrongful life sentence for murder and the dramatic denoument at the end of the novel which brings it full circle.

For Dickensian buffs like me the whole Hoo peninsula is worth exploring -particularly the places mentioned by Dickens in the opening and subsequent chapters of @great Expectations’ Dicken’s finest novel in my opinion..

I have yet to read Clewes’ novel and really must do.

Aside from the post on the filming of David Lean’s Great Expectations (mentioned in a comment above), I have written one other post on Dickens and the Hoo peninsula: Walking with Charles Dickens covers a walk to Cooling church (where ‘Pip’s graves’ can be found) and considers Dickens as walker

I grew up in Gravesend in the 1960s and 70s. One of our favourite walks was from Swigshole Cottage, where the RSPB warden lived, and where Sir Peter Scott nearly set up what he actually did at Slimbridge, across the marshes to Egypt and St Mary’s Bays. Here we saw white-fronted geese, (that had attracted Peter Scott), short eared owls, hares and lots of wading birds. A wonderful place in those days.

I now live in landlocked Wiltshire.

Thank you for this memory. I did not know about the near Peter Scott connection. I’ve walked from Swigshole to Egypt Bay several times. The route today is itself is somewhat plain (a wide, flat and overgrown track), but the marsh views to either side delight, and it is always a thrill to climb up the final slope and find the bay waiting there for you. Mostly sheep to be seen along the way, rabbits and the occasional stoat. RSPB Northward Hill is just to the west of there.

Wasn’t this where Jeffrey de Havilland junior was killed as a test pilot?

That’s correct, though I didn’t know it when I wrote the post.