There are some small out-of-the-way landing-places on the Thames and the Medway, where I do much of my summer idling. Running water is favourable to day-dreams, and a strong tidal river is the best of running water for mine.

I wish those words were mine. They fit so precisely with my thoughts and my location it feels almost as though I had written them. I idle by the Medway (occasionally the Thames as well); only it is never idling, for it is the flow of water, seemingly so slow that at times it appears not to be moving at all, yet remorselessly so beneath the surface, that by some process of osmosis gathers the flotsam of thoughts and leads them in a purposeful direction. Without day-dreams, we know nothing.

The words are by Charles Dickens, late of these parts, who died 150 years ago today. They come from ‘Chatham Dockyard’, one of the essays in The Uncommercial Traveller, a series published in Dickens’s newspaper All the Year Round over 1860, first brought together as a volume in 1861, with further series produced in 1863 and 1869, then collected in a volume which is the one we know today. To my mind it is among the finest of Dickens’s writings, certainly one to which I return always with the greatest pleasure. The series was initiated when Dickens was possibly at his peak as a writer (Great Expectations was published in serial form in All the Year Round at the same time). His eye and his pen were never more commanding that they were in 1860.

The Uncommercial Traveller is sort-of alter ego for Dickens. The inspiration for the name came from a talk Dickens gave to a meeting of the Society of Commercial Travellers’ Schools at the end of 1859. Commercial travellers, or travelling salesmen, were a distinctive product of the Victorian age; men (for they were usually men) who were the humble products of a rapidly changing consumer culture. The travelling and the selling meant too little reward for many (hence the Society, which had care of poor and orphaned children of salesmen). Dickens’s speech focussed on the philosophical side of the trade:

Gentlemen, we should remember tonight that we are all Travellers, and that every round we take converges nearer and nearer to our home; that all our little journeyings bring us together to one certain end; and that the good that we do, and the virtues that we show, and particularly the children that we rear, survive us through the long and unknown perspective of time.

Dickens’s Traveller became a journeyer though life and place, reporting on what he saw of how lives were lived, in places both celebrated and neglected, chiefly in London, but also Liverpool, France, Italy and the Medway towns. The papers are varied in style and quality. What is consistent about them is the voice of the ‘Uncommercial Traveller’ himself. It is not Dickens the novelist, or even the usual journalist in Dickens, but Dickens the conversationalist – half-talking to us as travelling companions, half-talking to himself. The mind ranges over past, present and future, gathering potential material for future novels, undoubtedly, but chiefly turning day-dreams into understanding.

‘Chatham Dockyard’ was part of the second series of The Uncommercial Traveller, published in the 29 August 1863 edition of All the Year Round. There are other essays in the volume that are personal favourites – ‘Two Views of a Cheap Theatre’, with its exhilarating account of a visit to Hoxton’s Britannia Theatre; ‘The City of the Absent’, with its musings on the unremarked people who rest for a while in London’s smaller churchyards; ‘Bound for the Great Salt Lake’, where he meets humble Britons entranced by the Church of Latter-Day Saints, about to sail from London to who knows what future for them in Utah (an ancestor of mine made just that journey). But ‘Chatham Dockyard’ and its geographical companion piece, ‘Dullborough Town’ (first published 30 June 1860) are two that I treasure in particular.

I live in Dullborough. It’s the unkind name Dickens gave to Rochester, his boyhood home, but he admits that it could be any place: “Most of us come from Dullborough who come from a country town”. It’s an essay with much that is strange about it. It is cast as though Dickens were returning to a place he had not seen since childhood, whereas in fact he revisited the town frequently, and by the time he wrote the piece he had been living for three years at Gad’s Hill, his house in nearby Higham. But the theme of the piece is change, which demands the conceit of childhood memory, and loss.

Dickens’s journey through Dullborough (it is one of the essays where the persona of ‘The Uncommercial Traveller’ is unavoidably that of Dickens himself) is one of muted disappointment. What he remember has gone; those he encounters have forgotten him, or have little interest him as an outsider. A greengrocer he remembered, still in the same place, the same trade, is sarcastic when Dickens tells him that he left the town when a child. Initially angry, Dickens calms down, observing that:

I was nothing to him: whereas he was the town, the cathedral, the bridge, the river, my childhood, and a large slice of my life, to me.

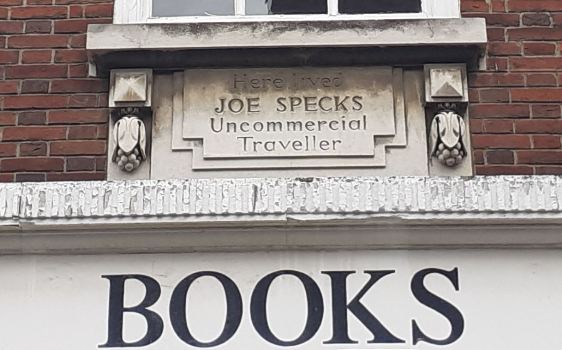

But then Dickens comes across an old school friend, now a doctor, Joe Specks. Specks initially does not recognise his childhood friend, but a shared anecdote brings them together, ending in a happy dinner that for Dickens helps resolve the “present to its past”. That meeting took place just across the road from where I live – there is a plaque on the wall to inform the passer-by that here lived Joe Specks (or supposedly so, since Specks is a made-up name, possibly based on a genuine friend of Dickens, though one must understand that some fictionalising has been exercised by the Uncommercial Traveller). So past and present are reconciled.

I set out from there for some travelling of my own. It was ‘Chatham Dockyard’ that I had in view, to my mind one of the best things Dickens ever wrote. It starts with Dickens in day-dreaming mode, wandering along the Medway riverside at Chatham, casting his eye over the shipping activity, the animals at pasture, the birdlife, in a disengaged frame of mind:

Watching these objects, I still am under no obligation to think about them, or even so much as see them, unless it perfectly suits my humour … Everything within range of the senses will, by the aid of the running water, lend itself to everything beyond that range, and work into a drowsy whole, not unlike a kind of tune, but for which there is no exact definition.

Engagement begins when he meets a boy near an old fort, who informs him of the history of every location and custom that surrounds them. The boy quite possibly was a real figure, but it is hard not to think that Dickens has encountered his phenomenally curious young self. The boy, whom he calls ‘the Spirit of the Fort’, wants to become an engineer, which focus inspires Dickens to seek out the Chatham dockyards.

The dockyards at Chatham were a prodigious sight. Home to the Royal Navy for 400 years, ships from Chatham went from wood to iron to steel, circumnavigated the globe countless times, and took part in conflicts from the Spanish Armada to Trafalgar to the Falklands War. Tens of thousands were employed there at its Victorian height. Given Britain’s global role as a naval power, nineteenth century Chatham was in some ways the hub of the world.

Dickens’s visit to the Yard shows us the industry, but also its paradoxical stillness. Industry first, though – Dickens steps into the middle of construction of the iron-clad Achilles, on which 1,200 men were working:

Ding, Clash, Dong, BANG, Boom, Rattle, Clash, BANG, Clink, BANG, Dong, BANG, Clatter, BANG BANG BANG!

He vividly describes a maelstrom of activity which contrives to be both documentary and hallucinatory in effect. He weaves in a surprising element of the natural into this vision of metal-driven industry, viewing the iron plates “as though they were so many leaves of trees”, later echoed when he enters an oar-making workshop and sees the wood shavings as butterflies. There is something natural in what might on first apprehension seem only alienating, nature interwoven with industry. This leads into the complementary sense of calm that Dickens detects, one bred of all parts of the colossal yet intricate business of constructing a ship.

All go methodically, quietly in a way, about their business, leading Dickens to identify this with “the retiring character of Yard”. He finds this in the Yard itself, in the workshops, in the business offices, in the transport cars hauling logs from place to place. Everywhere he sees

a staid pretence of having nothing worth mentioning to do, an avoidance of display, which I never saw out of England.

Dickens then binds all this together in a visit to the ropery, an essential part of the shipbuilding business, housed in a building over a thousand feet long. For Dickens, it provides a metaphor which draws not only the essay together but whole exercise in resolving past and present that is one of the underlying threads of The Uncommercial Traveller:

I am spun into a state of blissful indolence, wherein my rope of life seems to be so untwisted by the process as that I can see back to very early days indeed, when my bad dreams – they were frightful, though my more mature understanding has never made out why – were of an interminable sort of ropemaking, with long minute filaments for strands, which, when they were spun home together close to my eyes, occasioned screaming.

The rope of life, the filaments of time, connect Dickens the boy (who would have visited that very ropery) with Dickens the traveller, passing through places to connect past with present. It has been as much a psychological piece of reportage as a piece of journalism, connecting the stillness, or indolence, of the river scene with the industry that fed off the river’s location.

How different the Yard of today. Chatham Dockyard closed in 1984, triggering decades of decline across Chatham and the other Medway towns. The collapse of shipbuilding, the loss of ancillary industries, the shrinking of investment, the unemployment, all followed for a town whose purpose had gone.

The Historic Dockyard Chatham is now a tourist site, or was until the present lockdown brought, with bitter irony, a second (albeit temporary) closure of a hubbub of industry. Here one could tour the refurbished old buildings, board ships, see lifeboats and submarines, experience all the kinds of audio-visual explanations that the modern heritage explorer demands, and yes visit the ropery, whose outputs are echoed in the rope-themed attractions in the nearby children’s playground.

All is now empty and silent. The vast sheds, the machine shops, the pristine office buildings, the craft, afloat and lined up for display along the wharves. The thread has gone. Or not quite entirely, for one shipbuilding shed remains open for business, Turks Shipyard, an undercover dry dock keeping history alive.

Chatham is adjacent to Rochester. My travelling took me from Rochester high street, down the long connecting road between the two towns where no business ever seems to thrive, following the curve of the river away from the down-at-heel centre of Chatham to its northern reaches. Pausing for a while to visit the pleasing grounds of disused St Mary’s Church, with its neglected gravestones (some going back to the early eighteenth-century) and grand views over the bends of the river, I headed over the hill and down along a road severely lined on either side by high brick walls, til I came to the deserted Dockyard.

Beyond, to the right, is a complementary part of the attempted regeneration of this area, a retail centre bristling with shops, cafés, and entertainments, a monumental cinema among them. Here once stood the improbable Dickens World, which boasted a Great Expectations water ride, Fagin’s play area, an interactive Dotheboys schoolhouse, and gifts to be bought from the Old Curiosity Shoppe. A natural location for a time-travelling Dickens to have investigated, but a gift for any ironist, it closed in 2016.

A few figures mill about. Some queue outside the Co-op. Life, as everywhere, is on hold, though at the point of release. Unlockingdown.

Heading further north I pass by the marina, over which stands two huge residential towers. The water is filled with new boats. Here is the prosperity that is returning to Chatham. It is to be found at the edges, not in its sadly rundown centre. There is money here, drawn to the river views and a world beyond.

Further north and we come to St Mary’s Island, linked by narrow causeways to the mainland, a key part of the Chatham development area. Here is money again. Hugging the line of the river are rows of handsome weather-boarded houses, made tall to catch the best views, with a well-manicured esplanade. Dotted along the way are small coils of stone rope, tying the traveller to the dockyard, extending the metaphor.

The views across the river at this point are tremendous. To the south there is Rochester, its cathedral peeking out above the curves of the Medway, its adjacent castle viewable above a clump of trees on a nearer spit of land, proving the strategic value of its location. Opposite is the Hoo Peninsula, with its long wooded foreshore, pretty Upnor Castle, followed by lines of houses, ships and trees along the shoreline going north, then in the distance a nub of concentrated shipping gathered around Hoo Marina Park.

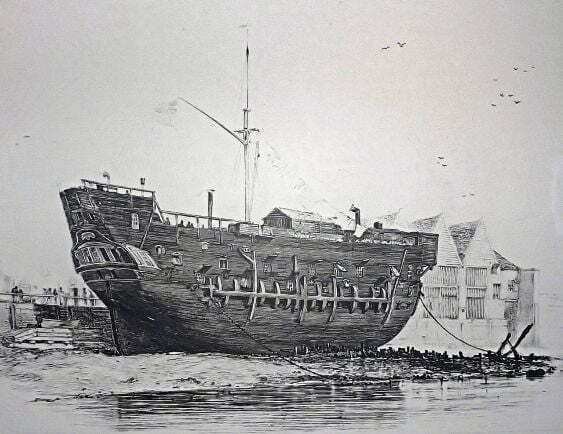

All is idyllic, a re-generator’s dream. But the past here was brutal. The Medway at St Mary’s Island was the location for the prison-ship hulks that were the epitome of human misery, from which Abel Magwitch escapes in Dickens’s Great Expectations. The Medway hulks were closed down around 1860, the year of The Uncommercial Traveller, but Dickens the child undoubtedly saw them, and it is through the eyes of the child Pip that we experience what he feels on encountering the terrifying Magwitch. As in all prison systems, the more dreadfully the condemned are incarcerated, the more dreadful do we feel they must be, to justify in our minds the nature of their punishment. It is the only way we can live with ourselves.

There is a vivid account of what life was life as a prisoner on one of the hulks (though not a Medway hulk) in the memoirs of former convict James Hardy Vaux:

I had now a new scene of misery to contemplate; and, of all the shocking scenes I had ever beheld, this was the most distressing. There were confined in this floating dungeon nearly six hundred men, most of them double-ironed; and the reader may conceive the horrible effects arising from the continual rattling of chains, the filth and vermin naturally produced by such a crowd of miserable inhabitants, the oaths and execrations constantly heard among them; and above all, from the shocking necessity of associating and communicating more or less with so depraved a set of beings.

Eye-witnesses recorded the heat and the smell as being unbearable. Hundreds of men were crammed into a deckspace too low in which to stand. Kept in irons, unable to move and barely able to breathe, fed rotting food that was barely enough to keep them alive, the convicts readily succumbed to every kind of sickness. Cholera, typhus and smallpox were endemic. Deaths were frequent, the bodies buried on the island or in the nearby marshes, such as the notorious Deadman’s Island, where human remains have been found as recent as 2016.

The logic is that the lowest must be treated in the lowest way; so it was that the guards were especially brutal. Vaux recalled:

These guards are most commonly of the lowest class of human beings; wretches devoid of all feeling; ignorant in the ex treme, brutal by nature, and rendered tyrannical and cruel by the consciousness of the power they possess …

Humanity likewise disappeared among the convicts themselves, for all that some had been friends in the outside world. Vaux documents the degredation in every sense:

I soon met with many of my old Botany Bay acquaintances, who were all eager to offer me their friendship and services, that is, with a view to rob me of what little I had; for in this place there is no other motive or subject for ingenuity. All former friendships or connexions are dissolved, and a man here will rob his best, benefactor, or even mess-mate, of an article worth one halfpenny … If I were to attempt a full description of the miseries endured in these ships, I could fill a volume; but I shall sum up all by stating, that besides robbery from each other, which is as common as cursing and swearing, I witnessed among the prisoners themselves, during the twelvemonth I remained with them, one deliberate murder, for which the perpetrator was executed at Maidstone, and one suicide; and that unnatural crimes are openly committed.

The hulk system was established in 1776, initially holding prisoners from the American revolutionary war. Decommissioned ships were turned into floating prisons, moored offshore in harbours. Often they were used as staging posts before convicts, such as Magwitch and Vaux, were transported to Australia. The convicts were regularly taken off-ship, if they had the strength to do so, to labour on shore (still in chains). Much of St Mary’s Island’s infrastructure was built in this way. One such project was a land-based prison on the island, designed to replace the hulks. St Mary’s Prison opened in 1856 and was the scene of major riot in 1861. 350 prisoners were involved, eventually taking control over the prison, destroying the interior. 700 troops prevented a mass escape and put down the riot. The ringleaders were identified and bloody mass floggings ensued, taking up the course of a day.

What happened to that vicious world? Its focus moved elsewhere, to other lands. The brutality became the stuff of fiction, history magazines, museum displays, and the informative display boards along the St Mary’s Island esplanade that seek to remind us of the unthinkable. Now all is still and gentle. St Mary’s Island is haven of riverwalks, cycle paths and pleasing houses. It seems the epitome of neighbourhood. People, coming back to life, stroll by in twos, pointing out the views to each other. A jogger, limbs thick with the tattoos that once would have been the pride of a convict, lopes into the distance.

At the top of the island is a splendid statue, by Sam Holland, entitled ‘The Mariners’. A man and woman at either side of the base lean backwards, gripping ropes from the ropery to haul up the sails, the very expression of strength, industry and community. The river flows beyond.

There is a stillness to St Mary’s Island that Dickens would recognise. It is a place where bad dreams have been overlaid by prosperity, but still those long minute filaments stretch back into time. They make our perceptions nervous. We could be a rope thread’s width away from all that is hateful in ourselves.

‘Chatham Dockyard’ is about the calm in the eye of the storm. The roar of industry is offset by the quiet business of labour. The bad dreams of the past are lost to blissful indolence. It complements Dickens’ other great work of that time, Great Expectations, in connecting the past with the present, the child with the adult. Pip finds in Magwitch not the terrible vision of his childhood, but the father-figure he never knew. Humanity had survived through the hulks. We turn things for the better, in time.

Links:

- Text of The Uncommercial Traveller can be found in the issues of All the Year Round via Dickens Journals Online, including ‘Chatham Dockyard‘

- What survives of Dickens World can be found on the website archived on the Internet Archive

- The Historic Dockyard Chatham provides details of all the attractions that will return, in time

- The is a fine website on the history and craft of ropemaking produced by Master Ropemakers of Chatham

- The text of The Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux is available on Hathi Trust

- There is a good account of a day on the hulks written by Anna McKay, on the University of Leicester’s Carceral Archipelago blog. Interestingly it argues for a slim positive side to life on the hulks (“After all, prisoners were provided with three meals a day. They mastered trades and learnt to read and write. When released, they were even given a little money.”)

- Wikipedia has a concise history of St Mary’s Island and its re-development