Something in all of us yearns for the sea.

I am travelling on a train. I don’t know when exactly; it might be the late 1980s or early 1990s. The train has come from London and is heading along the north Kent coast. I am headed for Whitstable, to see family. It is summertime, and the train is filled with families on a day trip to a beach anywhere along the coast. The children are frustrated. They have been travelling for an hour or so, and all that can be seen out of the windows is featureless fields broken up by the occasional nondescript town. Buckets and spades and picnic baskets rest on the seats, lost of purpose.

Then there is change. Land and trainline dovetail together dramatically, rushing towards a single point. We swoop to the left as the land flattens and the town nears. Houses appear, and a coastline announces itself suddenly, thrillingly. The children leap up and call out, ‘The sea! The sea!’ Between the pebbled beaches and the cloud-scudded sky, there is the vast stretch of water, filling the vacancy, lifting all young hopes. I feel elated with them and for them. And somehow, in the memory, the tide is always in, because we need it to be. The sea, the sea.

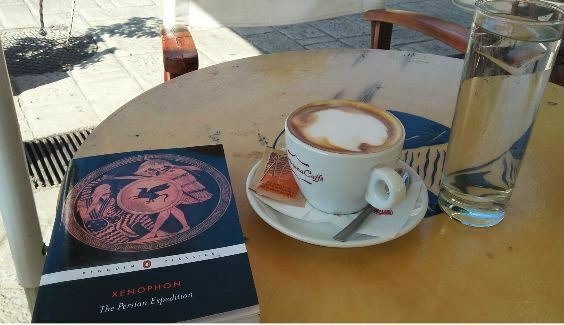

It is February 2019. I am seated at a café in Old Corinth, at the north-eastern tip of the Greek Peloponnese. Modern Corinth is on the coast, but the old city is three miles inland, to the south-west. It is off-season, but the weather is clement. The crowds are few. I have visited the ruins, criss-crossing every wall and path in the search for comprehension, photographing every angle for the memory.

At the café, with my coffee and glass of water, I read from my Penguin copy of Xenophon‘s The Persian Expedition, known as Anabasis to the scholars. The Greek soldier-turned-historian lived here and may have written his history here, the unsurpassed account of a troop of Greek mercenaries (the Ten Thousand) who in 401 B.C. chose the losing side when they signed up to fight for the Persian Cyrus against the armies of Artaxerxes II, whom he wished to usurp. Captured after the Battle of Cunaxa, with Cyrus dead and their leaders betrayed and executed, the Ten Thousand escaped. One of the greatest of all adventures now unfolded.

Deep in what is now Iraq, they had to head north through challenging terrain to the coast of the Black Sea, before veering left and back to Greece, a journey of some 1,000 miles. Xenophon was one of their new leaders. Harassed by the pursuing Persians, often desperate for food, beset by bitter winter weather, they were forced repeatedly to do battle with hostile peoples of alien customs and mysterious languages, many of whom we know only through Xenophon’s account. It was a phantasmagorical journey worthy of Homeric myth, only every step was true. One senses the frail forces of civilisation (albeit in the form of mercenaries whose motives had been less than noble), beset on every side by barbarianism, by peoples set only for extinction. In some strange sense, our survival owes itself to theirs.

At what is believed to be Trabzon (now part of Turkey) they reach the Black Sea. The passage was once the favourite of every Classics teacher, thrilling generations of schoolchildren for whom Ancient Greek history formed the backbone of political, cultural and military understanding. Here is the passage, in H.G. Dakyns’s translation:

No sooner had the men in front ascended it and caught sight of the sea than a great cry arose, and Xenophon, in the rearguard, catching the sound of it, conjectured that another set of enemies must surely be attacking in front; for they were followed by the inhabitants of the country, which was all aflame … But as the shout became louder and nearer, and those who from time to time came up, began racing at the top of their speed towards the shouters, and the shouting continually recommenced with yet greater volume as the numbers increased, Xenophon settled in his mind that something extraordinary must have happened, so he mounted his horse, and taking with him Lycius and the cavalry, he galloped to the rescue. Presently they could hear the soldiers shouting and passing on the joyful word, “The sea! the sea!”

In Greek the great shout they gave was ‘Thalatta! Thalatta!’ – ‘Θάλαττα! θάλαττα’. The sea meant a destination, self-determination, the end of hopelessness, life itself. Xenophon tells us that the Greek had tears in their eyes.

It is towards the end of June 2020. I must see the sea. A virus has stricken the land, and for the past three months we have been largely confined to our homes. The lockdown, as it is called, is starting to come to an end, by instruction or because it is breaking down anyway. We need to be somewhere else. I have not seen the sea in a long while. It promises release. I think of the children on that Whitstable train, of Xenophon’s men wildly uplifted by hope. I have the script before me.

Being obedient, I do not travel anywhere by train, since my journey is not necessary – at least not in the prosaic sense of things. So I walk. I walk from Rochester northwards over the eastern side of the Hoo peninsula, a flatland area with fields like prairies, empty roads, infrequent villages, and heavy industry to the edges (the Isle of Grain forms the north-eastern tip of the land). It is startling to walk through such emptiness, so near to the crowded towns of the Kent coast. But there is a sense of sadness too, because it will not be so empty for long for long – the building plans have been made, homes must be found, it is a canvas waiting for the painter.

It takes five hours to get to Allhallows-on-sea. There is an old village inland, Hoo All Hallows, but Allhallows-on-sea is the fateful product of a dream of holidayers who would be happy to come to this desolate corner if only a train line was laid. The line was laid in 1932. Nobody came. The line closed in 1961. The war put paid to the hopes of a holiday resort to rival anything in Europe. Today, a caravan park greets the hardy visitor with a poster announcing, more in surprise than in boastfulness, “750 caravan owners – we must be doing something right’.

I weave my way through the caravans, down the grassy slope, to the coastline. The sea is not there.

Seas come with tides, but one can hardy imagine one quite so dramatic as that at Allhallows. The sea – for it is out there – must be some two miles distant. A featureless flatness spreads in every direction. The absence of any feature is stunning to contemplate. Here is being and nothingness.

There is shingle and there are groynes. There are a few gulls. I can see the sea was here once. A few families are sitting on the pebbles, with their backs to the emptiness. Some figures stand picturesquely on the distant mudflats, as though positioned on instruction for a Turner painting. There are a couple of container ships far out in the distance. Beyond is Canvey Island, the Essex resort that became all that Allhallows did not. Here is where the Thames meets with the sea, and the oceans, and the waters that ultimately all connect with one another.

I cannot say ‘The sea, the sea’, though I urgently want to do so. I could stay for three or four hours and witness the tides come surging back, but I must go back. The long walk home awaits. Another time I will return, because I love the desolation of these places. They strip away all illusions. The revelation that beneath the promising, hope-giving waters lies such emptiness must make a philosopher of anyone.

These are the choices – we can sail away to somewhere, or we can contemplate the endless plain.

Links:

- There’s a Flickr album of my walk from Rochester to Allhallows. It’s fine country

.