The greatest songs are those that demand to be sung again. The reasons for wanting to do so can differ. It may be for the song’s great popularity among a particular set of people, who find self-identification in hearing it once again. It may be in the quality of the songwriting, whose subtleties compel the listener to absorb it repeatedly. Or it may be that there is a mystery, never resolved, that makes us listen once more in the vain hope of finding an answer this time around. Just such a song is ‘In the Pines‘.

My girl, my girl, don’t lie to me

Tell me where did you sleep last night?

In the pines, in the pines

Where the sun don’t ever shine

I would shiver the whole night through

The song’s roots lie in the 1870s with the coming together of two songs, or song clusters (i.e. variants), ‘In the Pines’ and ‘The Longest Train’. The first centred around a young woman being questioned about her disappearance. The second concerned a train wreck that ended in a decapitation (originally of a woman, later of a man). How the two songs came together is unclear, though it may have been trains that formed the link, one being about the longest train, the other containing the decapitation detail and the ‘pines’ refrain. This has led to incongruities in some of the recorded versions, which start with the girl telling us of her night in the pines, then trip us up with lines such as “The longest train I ever saw went down that Georgia line / The engine it stopped at a six-miles post, the cabin it never left town”. Where is the connection? It is a fragment of a memory, with the logic that only memory can provide.

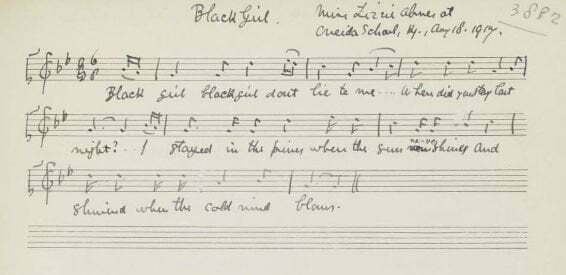

Whatever the synthesis, their half-fit helps give ‘In the Pines’ its peculiar quality. Effectively it remains two inter-related song clusters, some versions favouring the train narrative, some the girl being questioned, some mixing up the two. Versions have been recorded under the titles ‘Black Girl’, ‘What Did You Sleep Last Night?’, ‘In the Pines’, ‘The Longest Train’, ‘Lonesome Railroad’, ‘My Girl’, ‘Georgia Pines’ and several more. Musicologist Judith McCulloh, for her 1970 PhD, traced 160 variations of the song between 1917 (when it was documented by English folk song collectors Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles on a field trip through the Appalachians) and 1969. There is no definitive version; that too is a part of the mystery. What links most of them is some version of the ‘pines’ refrain, the oblique metaphor whose recollection is its own justification.

My girl, my girl, where will you go

I’m going where the cold wind blows

In the pines, in the pines where the sun don’t ever shine

I would shiver the whole night through

What actual stories might lie behind ‘In the Pines’ have been the subject of much debate. Some early versions reference ‘Joe Brown’s coal mine’, which McCulloh proposes is a reference to a mine-owning Georgia governor of that name in the 1870s. But the girl returning from the pines feels timeless. ‘In the Pines’ is enriched by the coming together of the eternal and the specific, as though each side were trying to make sense of the other.

The song is more folk ballad than blues. In the song’s classic form it adheres to standard traditional ballad practice, in which the listener is confronted by the story in media res, i.e. at its crisis point rather than from the start. A lot has happened before than opening question, “My girl, my girl, don’t lie to me / Tell me where did you sleep last night?” The ballad is a narrative of crisis and consequences. It also shares the ballads’ particular use of imagery. M.J.C. Hodgart, in The Ballads (1950), writes that their “imagery is of a peculiar kind … there are few original figures of speech; and the effect is usually symbolic rather than decorative”. This is exactly how ‘In the Pines’, in its classic form, functions. The scene is wholly internalised.

The opening question is a standard motif in many a blues song: a lover’s complaint at betrayal. But ‘In the Pines’ has an existential quality to it, partly sexual in origin, undoubtedly, one of transgression, loss and emptiness. The girl replies as though presenting a riddle (another standard ballad trope) but in doing so usually just says the same words over and over again: “In the pines, in the pines, where the sun don’t ever shine / I would shiver the whole night through”. It is the voice of trauma.

It is not clear who is asking the questions. The assumption at the start is that it is a lover, but the tone suggests just as much an anxious parent. Yet several versions of the song refer to the mother in a third person. A grandmother is referenced in the earliest commercially recorded version of the song (by Dock Walsh, in 1925). The relationship between singer and subject is never fully realised.

Her husband, was a hard working man

Killed a mile and half from here

His head was found in a driving wheel

And his body has never been found

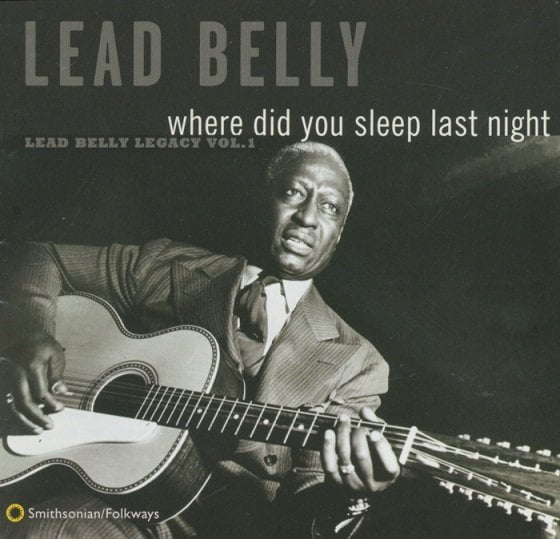

The essential complement to the song’s unsettling quality is the tune, as least that established by blues/folk singer Lead Belly in the 1930s, though the basic melody is there in Cecil Sharp’s 1917 transcription. According to folklorist Alan Lomax (reported by McCulloh), Lead Belly picked up the song from Sharp’s work, with some reference to Dock Walsh’s 1925 recording, cementing the musical idea in the process. In simple chordal form, it’s a standard E, B7 and A, followed a surprise G, which arrests the ear while accentuating the crisis. It is a falling sound, the minor quality of major chords revealed. The effect is compounded by a usual 3/4 waltz time beat, a rocking, lulling quality that echoes the question and response structure.

Another distinctive quality of the song is its cross-racial nature. One or other of its ur-versions may have derived from the white Appalachian community, but it was swiftly (or simultaneously) adopted by black singers, who presumably gave one of the variants the ‘Black girl’ phrase (it is there in the 1917 Sharp/Karpeles transcription from white singer Lizzie Abner). Lead Belly is said to have sung ‘Black girl’ for black audiences and ‘My girl’ for white. It’s a shape-shifting song, whose variations are an inevitable reflection of the societies that have adopted it. One could go so far as to say that its main variants reflect a divided society: white versus black, contented versus discontented, lonesome versus lost. Equally, however, one can see it as emblematic of a diverse society profoundly linked by a shared folk heritage. Folksong, of which ‘In the Pines’ is a pre-eminent example, is song owned by the folk, transmitted by word of mouth, rooted in common experience.

The most influential recordings have been those by Bill Monroe, Lead Belly and Nathan Abshire. Bluegrass pioneer Monroe, who first recorded ‘In the Pines’ in 1941, emphasises the train narrative through a theme of lost love, though the ‘in the pines’ lines remain. What has gone is the questioning of the girl. Lead Belly, who made several versions with that death-knell G, indelibly shaped the interrogative version of the song (the lyrics in this post come from his 1944 recording, entitled ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?’), most notably the anguished version recorded by Nirvana only a few months before singer Kurt Cobain’s death. A third, wildly different Cajun version, ‘Pine Groves Blues’, was initiated by a sensational 1949 recording made by Nathan Abshire. It nods to the key phrases but musically derives from a 1930s song ‘Le Blues de Petit Chien’ that has no connection with ‘In the Pines’. The exuberant results are the antithesis of the darkness trademarked by Lead Belly.

The history of ‘In the Pines’ is of a shedding of specificity in pursuit of mystery. Various versions have carved away the details to leave a song that seems as lost as its protagonist. The answer to its mystery lies in all that is left behind.

My girl, my girl, don’t you lie to me

Tell me where did you sleep last night

In the pines, in the pines where the sun don’t ever shine

I would shiver the whole night through

Some while ago now I explored excellence in guitar, bass, drums and singing. Having identified an unlikely quartet (Mike Oldfield, George ‘Fully’ Fullwood, Jaki Liebezeit and Sandy Denny), I wanted to find something for them to play. Having tried out some genres (blues, country, reggae) it is time to select songs for them to play. ‘In the Pines’ is the first; others will follow. Before doing so, they might like to consider some of the finest ways in which the song has been recorded. Then they should forget them all and produce something uniquely their own, of course.

So, as before, here is a top ten of personal favourites, followed by a Spotify playlist of these and more. It’s an odd thing to suggest listening to ten versions of the same song, but that’s the peculiar quality of ‘In the Pines’, with its unresolved question. All we can do is ask again, listen again, and listen again.

10. Fantastic Negrito, ‘In the Pines (Oakland)‘

Rootsy American singer-songwriter Fantastic Negrito (real name Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz) delivers a version fit for our times. It has the smart, knowing production of modern R&B, underpinned by a jackhammer beat and mournful humming to evoke traditional worksongs. This could be a song from 2016; it could be a song from 1870.

9. Vieux Farka Touré and Julia Easterlin, ‘In the Pines’

Here is one of the most intriguing and beguiling versions of ‘In the Pines’, courtesy of a collaboration between the great Malian singer and guitarist Vieux Farka Touré, and American singer Julia Easterlin, whose vocals are as much incantation as sung. Though the production is a little on the tricksy side, this is music freed from barriers that puts the song on a global stage.

8. The Browns, ‘In the Pines’

The Browns were an American vocal trio who sang close harmony country pop for a conservative 1950s audience. They might be the last people you would expect to tackle the darker side of ‘In the Pines’, but this version is eerie. Distinguished by an off-kilter piano figure and hushed vocals, it make little sense as narrative (it is a classic example of the narrative mismatch of girl in the pines and the railroad themes) but succeeds entirely as the evocation of a dream. It is the version of the song David Lynch would choose.

7. Wanda Davis, ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?’

American soul singer Wanda Davis, active in the late 60s and 70s, released just one 45 (now highly collectable) before retiring. Forty years later she was persuaded to come into the studio again and produce this spooky, soulful version of the folk standard. It sounds exactly like a lost Northern soul classic, at once pastiche and absolutely the genuine article.

6. Bill Monroe, ‘In the Pines’

This is the classic rendition of the ‘longest train’ variant, recorded in 1941 by Bill ‘Father of Bluegrass’ Monroe. It is sweet and mournful, with scarcely a trace of darkness, even though the most of the key elements are there (there’s no mention of decapitation) and a bleak addition of its own: “I asked my captain for the time of day / He said he throwed his watch away”. It’s the train whistle ‘woo-woos’ of the harmonies that show us where this variant is heading.

5. Odetta, ‘In the Pines’

This gracious version, from a 2001 album of Lead Belly covers (the last studio album Odetta made), is quite unlike any other in the canon. It is piano-led, gentle in tone, and filled with understanding. Maybe it finds the voice of both the mother and the girl. Certainly it takes the song in a new direction, making you treasure it anew.

4. The Kossoy Sisters, ‘In the Pines’

The Kossoy Sisters (identical twins Irene Saletan and Ellen Christenson) are an American folk duo, whose 1956 album Bowling Green is a particularly fine collection of close-harmony renditions of traditional folksongs (it includes the version of ‘I’ll Fly Away’ that features so sweetly in the Coen brothers’ film O Brother Where Art Thou). Their interpretation of ‘In the Pines’ gets the tone just right: understated, haunting, unsettling for some reason that the listener cannot quite identify yet cannot ignore.

3. Nathan Abshire, ‘Pine Grove Blues’

The Cajun version of ‘In the Pines’ really is a different song, for all that it uses the same question (‘i’Hé, négresse! ayoù toi t’as partir hier au soir, ma négresse?’ / ‘Hey, black woman! Where did you go last night, my black woman?’). The words are merely there as a trigger for the musical accompaniment, which is just plain glorious (especially so when the fiddle solo kicks in). Nathan Abshire was a Louisiana accordionist who revitalised the Cajun genre in the 1940s. ‘Pine Grove Blues’ was his signature recording.

2. The Four Pennies, ‘Black Girl’

The Four Pennies were a short-lived pop group from Blackburn who failed to capitalise on the 1960s British beat boom. Their version of ‘In the Pines’, quite boldly entitled ‘Black Girl’, reached number 20 in the British charts. It sounds initially as though it is going to be only moderately interesting. But then the energy builds, the drums hammer loudly, and the raw music rises to match the song’s great potential. It’s a strange, exhilarating rendition. Had Nirvana been around in 1964, this is what they might have sounded like.

1. Lead Belly, ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?

Huddie Ledbetter (1888-1949), known as Leadbelly, and now more usually as Lead Belly, recorded the song a number of times. The 1944 version is probably the definitive one. Accompanied by his chopping, twelve-string guitar and a second voice responding to his words, it has a calm majesty about it that no other rendition can match. It has the voice of one who has seen, understood, and moved on. Maybe only Lead Belly truly understood the question and what was there in the pines.

Need to hear more? Here’s a list of many, though certainly not all, of the recordings available on Spotify. They range from the 1920s to the 2010s, with an emphasis on variety and distinctive quality: all of those mentioned above, plus Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, the Triffids, Gene Clark, Marianne Faithfull, the Grateful Dead, Joan Baez, Link Wray, Sir Douglas Quintet and many more. I’ll keeping adding to the list, and would welcome suggestions.

Links:

- The Wikipedia page on ‘In the Pines‘ is well-written and informative. Among printed sources Norm Cohen, Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in American Folk Song (University of Illinois Press, 2000) is very useful, not least for distilling information from Judith McCulloh’s unpublished PhD. Also good is the section on the song in Mary-Anne Constantine, Fragments and Meaning in Traditional Song: From the Blues to the Baltic (Oxford University Press, 2003)

- There’s an interesting article on Slate, ‘The Haunting Power of “In The Pines”‘, which traces the history and popularity of the song, centred on the version by Nirvana

- Ultimate Guitar has the chords for the Lead Belly version

- Lyrics to some of the commercial versions of the song can be found on sites such as Genius and MetroLyrics. The Cajun French lyrics to ‘Pine Groves Blues’ (with English translation) can be found on Cajun Lyrics

- ‘In the Pines’ is one of five songs imaginatively realised in graphic artist Erik Kriek’s 2018 collection In the Pines: 5 Murder Ballads

Such a great song, and so many great covers. Thanks for the detailed review!

Thank you. I still can’t work whether it’s one song or any number of songs that just happen to sound alike.