In the heart of the City of London, at the corner of Poultry and Queen Victoria Street, stands a striking modernist pink stone building. No. 1 Poultry Street is the youngest listed building in the country (it was granted grade II* status in 2016), but the site it occupies has a long history. Tucked around the back of the building a plaque tells us that here once stood St Benet Sherehog, a medieval church memorably named which stood for over 500 years before it was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, never to be rebuilt. Among those who were buried there, their graves now lost, were the poet Katherine Philips and her son Hector. He had died in 1655, having lived a mere forty days. Of his death she wrote, in one of her most memorable poems, ‘Orinda upon little Hector Philips’:

I did but see him, and he dis-appear’d,

I did but touch the Rose-bud and it fell;

A sorrow unforeseen and scarcely fear’d,

For ill can Mortals their afflictions spell.

She herself died young in 1664, aged 33, of smallpox, just two years before her place of burial was destroyed in the Fire. Yet probably she would not have been moved by such a turn of events. In ‘Wiston Vault’ she writes of the vanity of tombs and epitaphs:

Ah, false vain task of art! ah, poor weak man

Whose monument does more than’s merit can!

Who by his friends’ best care and love’s abused,

And in his very epitaph accused;

For did they not suspect his name would fall,

There would not need an epitaph at all.

For Philips, the things of the heart were of greater permanence than any man-built monument. This the theme and the ambition of her poetry.

Katherine Philips (1631-1664) is a case study in the fall and rise of posthumous reputations. In her day she was the ‘Matchless Orinda’. That was how her admiring peers referred to her, and what a splendid a title it is. ‘Orinda’ was the name that she gave to herself in her poetry, giving similar classical names to the family and friends to whom she frequently addressed her poems, among them ‘Antenor’ (her husband James Philips), ‘Rosania’ (her childhood friend Mary Aubrey) and especially ‘Lucasia’, the name given to Anne Owen, to whom nearly half her surviving verse was addressed. She was the daughter of Puritans, who then married a supporter of Cromwell, but whose political persuasions turned increasingly royalist. She was raised in London, but spent much of her adult life in Cardigan, Wales, her husband’s seat, where she chafed at her remote location and the poor society, while doing her best to rationalise her situation in verse (from ‘A Country Life’):

Opinion is the rate of things,

From hence our peace doth flow,

I have a better fate than kings,

Because I think it so.

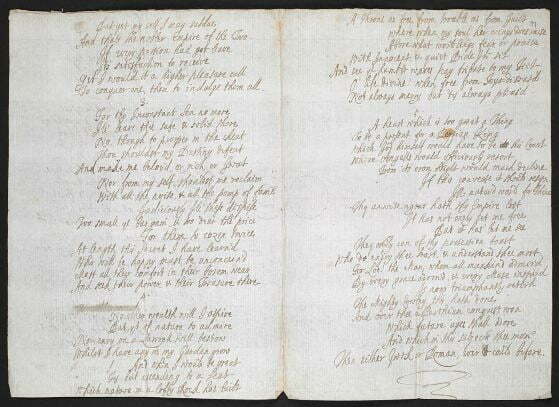

She responded by developing an intense communication through poetry, shared in manuscript form with friends and the literary cognoscenti of the time, augmented by letters which debated philosophical ideas. She became one of the most highly respected poets of her age, championed for her lyric gift and intellectual insight. She was praised in particular as a woman writer, whose work was distinctive because of her fresh insight (“We our old Title plead in vain; / Man may be Head, but Woman’s now the Brain” writes Abraham Cowley, in one of the many lavish commendatory verses written following her untimely death). It was a reputation gained almost entirely without publication, since she circulated her poems through manuscripts, which were read and shared by the intellectual few. Only in the last year of her life was a collection of her poems published (a few verses had been published in 1651), and that a pirated version to which she objected strongly (in public, at least). An official collected poems only appeared posthumously, in 1667. Samuel Pepys records reading it in his diary entry for 16 September of that year.

Thereafter, despite further championing by John Dryden and John Keats, her reputation faded. It revived to a degree following the publication, in 1905, of George Saintsbury’s Minor Poets of the Caroline Period, which reproduced the 1667 collection in its entirety. Her poems were thereafter to be found in anthologies, often of so-called minor or lesser poets, compiled by such diligent editors as Norman Ault (Seventeenth Century Lyrics), H.J. Massingham (Seventeenth Century English Verse), J.C. Squire (The Cambridge Book of Lesser Poets), or John and Constance Masefield, whose Lyrists of the Restoration was where I first came across her, transfixed in particular by the startling opening lines of ‘Parting with Lucasia’:

Well, we will do that rigid thing

Which makes spectators think we part;

Though absence hath for none a sting

But those who keep each other’s heart.

But despite the anthologies, she remained almost invisible. A biography appeared in 1931, The Matchless Orinda, by Philip Webster Souers, but though he investigated her life and works in depth and sympathetically, he stated her reputation was not, and now could never be, what it once had been: “she is merely a minor poet of the seventeenth century, whose glory has departed”. My revered Penguin Companion to English Literature (1971), through which I found so much to explore and cherish, had no entry on her at all.

But with a growth of interest in women’s literary heritage, driven by an imperative to rebalance the traditional understanding of our literary inheritance, her name came into the ascendant once more. Germaine Greer’s 1989 Kissing the Rod: An Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Women’s Verse did much to excite interest in her work. Now, though much of what is written about her is in highly academic, specialist texts, she is once more revered by the cognoscenti. No volume of her poetry is currently available, but a new edition of her poems and plays is in preparation (Greer’s Stump Cross Books published a three-volume set of her writings in 1990/92, but all are out of print). She has the character, insight, euphony and relevance to guarantee her wide appeal. She could be once again be as revered, and understood, as she was when alive.

So, what is so special about Katherine Philips?

Obviously, there is her unusual status as a female writer in the seventeenth century; once a figure of curiosity, now a key figure in a feminist revision of literary history. There were very few women writers (in Britain or elsewhere) at the time, simply through a general lack of education and opportunity. Philips was not the first British woman to write poetry or to be published, but she was arguably the first prominent such figure (poet and prose writer Margaret Cavendish published before her, and yes, Queen Elizabeth wrote poetry, but she became prominent for other reasons). She broke through in part through exceptional intellectual ability (a brilliant child, she is said to have read the whole of the Bible by the age of four). There must also have been a degree of family support, but chiefly she wrote because she had to write. Philips thought and communicated poetically. Her poems are conversations carried on by other means, often responding to events personal or political. She lived at a time when manuscript poems were often circulated and read with close attention for content and style. She was accepted and admired in her time for so eloquently expressing herself in the modes of the time.

Here, for example, are the opening stanzas of ‘Friendship in Emblem, or the Seal, to my Dearest Lucasia’:

The hearts thus intermixed speak

A love that no bold shock can break;

For joyn’d and growing both in one,

Neither can be disturb’d alone.That means a mutual Knowledge too;

For what is’t either heart can do,

Which by its panting Centinel

It does not the other tell?That Friendship Hearts so much refines,

It nothing but it self designs:

The hearts are free from lower ends,

For each point to the other tends.

In its ingenuity of argument combined with an elegant elusiveness, this owes much to the metaphysical poets (Philips admired Donne, was Marvell’s contemporary, and knew Cowley and Vaughan). In the way that it plays with the image of an emblem as visual metaphor it turns the idea of friendship into something abstract yet at the same time deeply felt. It quickens the senses even as the versification beguiles.

Friendship was her great poetic theme. She cultivated the idea of a society of friendship, and expressed an intensity of feeling towards her women friends that has led to inevitable speculation about her sexuality. It is only speculation, much of it based on an interpretation of language and emotion that would have been seen quite differently in the seventeenth century. Reading her biography, one does sense that the target of much of her poetry, Anne Owen (‘Lucasia’), was on occasion somewhat taken aback by the strength of Philips’ expression of friendship, as in the raw opening to ‘Orinda to Lucasia parting, October, 1661, at London’, written in a fit of despair at the news that Owen was moving to Ireland to marry:

Adieu, dear Object of my Love’s excess,

And with thee all my hopes of happiness,

With the same fervent and unchanged heart

Which did its whole self once to thee impart,

(and which, though fortune has so sorely bruis’d,

Would suffer more, to be from this excus’d)

I to resign thy dear converse submit,

Since I can neither keep, nor merit it.

Thou hast too long to me confined been,

Who ruin am without, passion within.

Concise expressions that memorably marry thought and feeling such as that last line are found throughout Philips’ poetry. Her concept of friendship was highly conceptualised. She wrote frequently of the intermingling of souls, viewing friendship as a mystical goal, expressed through elegantly contrived metaphor. The idealist poet was tied to drab, remote Cardigan, but in her mind she could reach for Arcadia, through verse and female friendship. In the beautifully constructed ‘Content, to My Dearest Lucasia’, she lists, describes and rejects all forms of contentment, save that of content in its ideal form, which is friendship:

… Then, my Lucasia, we who have

Whatever Love can give or crave,

With scorn or pity can survey

The Trifles which the most betray.

With innocence and perfect friendship fir’d,

By Virtue join’d, and by our Choice retir’d;Whose Mirrors are the Crystal Brooks

Or else each other’s Hearts and Looks,

Who cannot wish for other things,

Than Privacy and Friendship brings,

Whose thoughts and persons chang’d and mixt are one

Enjoy Content, or else the World has none.

She wrote on public affairs as well, in particular the return of the monarchy following the Civil War and Protectorate, though her royalist sympathies clashed with her husband’s parliamentary role and could have put him in danger, before Charles II’s return. One poem in particular, ‘Upon the Double Murder of King Charles I’, set tongues wagging, leading to the worried tone of ‘To Antenor, on a Paper of Mine which J. Jones Threatens to Publish to Prejudice Him’ (Antenor is her husband, J. Jones the puritan cleric Jenkin Jones):

Must then my crimes become his scandal too?

Why, sure the devil hath not much to do.

The weakness of the other charge is clear,

Which such a trifle must bring up the rear.

It is remarkable the degree to which Philips would express her private thoughts for sharing as manuscript poems. Of course, they were for sharing among friends, but there is an unguarded quality to them that is surprising to find written down and distributed. She could not help but speak her thoughts, only half-protected by the formalities of verse. However, though she could be unguarded, she was also subtle. Souers, her biographer, speculates that the royalist enthusiasm of her post-Restoration verse could have been intended to protect her husband, who had been Cromwell’s man, through expressions of loyalty. If so, the stratagem worked, as James Philips survived to serve as MP for Cardigan in the Cavalier parliament (though political machinations caused him to lose his seat within a year).

There is dull stuff among her poetry, with some formulaic panegyrics, while some discussions of events are little more than chit-chat. That must be inevitable when poetry has become, to a degree, how you speak. The best of it, however, charms and elevates, filled as it is with the clear-cut cadences and rhythm that so distinguish the best poetry of her era. Few poems from her century are so gently crafted, so astutely expressed, as ‘To my Excellent Lucasia, on our Friendship’, given here in full:

I did not live until this time

Crown’d my felicity,

When I could say without a crime,

I am not thine, but Thee.This carcass breath’d, and walkt, and slept,

So that the World believ’d

There was a soul the motions kept;

But they were all deceiv’d.For as a watch by art is wound

To motion, such was mine:

But never had Orinda found

A soul till she found thine;Which now inspires, cures and supplies,

And guides my darkened breast:

For thou art all that I can prize,

My Joy, my life, my Rest.No bridegroom’s nor crown-conqueror’s mirth

To mine compar’d can be:

They have but pieces of this Earth,

I’ve all the World in thee.Then let our flames still light and shine,

And no false fear control,

As innocent as our design,

Immortal as our soul.

Katherine Philips was once a minor poet, but we no longer have such things in our literary histories. The old hierarchies have gone, freeing matters up to permit multiple viewpoints and fresh perspectives. She is anyone’s equal, and should be. Yet there is part of me that regrets the loss of those ‘minor’ and ‘lesser’ labels. They pointed to history’s modest corners, to people whose charm lay in part that they had been overlooked. Philips quite liked the idea of being overlooked, or claimed as much:

That private shade, wherein my Muse was bred,

She always hop’d might hide her humble head …

Those lines open what was her last poem, ‘To his Grace Gilbert, Lord Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, July [sic] 10, 1664’ (she died on June 22, so the month must be a misprint). Lesser poets speak not to the crowd but to us alone. We find them in musty volumes, long neglected on the shelves, discoveries to cherish as our own. They are tucked around the back of things, most comfortable in their modesty.

So do read Katherine Philips; but also keep her to yourself.

This is the third in an occasional series of posts on favourite poets of mine

Links:

- The best-available volume for discovering Philips’ poetry is Sarah C.E. Ross and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann (eds.), Women Poets of the English Civil War (Manchester University Press, 2018), which has a good selection of her poetry with helpful background history and notes

- Germaine Greer’s Slip-shod Sibyls: Recognition, Rejection and the Woman Poet (Viking, 1995) has an illuminating chapter on the differences between the manuscript and printed versions of Phillips’ poetry, questioning where the poet’s authentic voice lies. For example, the original printed version of ‘Orinda upon little Hector Philips’ (quoted at the start of this post) has the line ‘I did but pluck the Rose-bud and it fell’. In manuscript it reads, ‘I did but touch the rosebud and it fell’, which I have preferred. All the difference in the world

- A 1770 edition of Philips’ poetry, plays and translations can be found on the Internet Archive; George Saintsbury’s Minor Poets of the Caroline Period vol. 1 with poems and songs from the plays is available on Hathi Trust, as is Philip Webster Souers’ biography The Matchless Orinda

- The British Library’s Discovering Literature site has a short biography of Katherine Philips and an essay ‘Print and perception: The literary careers of Margaret Cavendish and Katherine Philips‘ by Tamara Tubb

- There is a listing of her extant manuscripts on the Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts 1450-1700

- And she has a Twitter account. Of course.