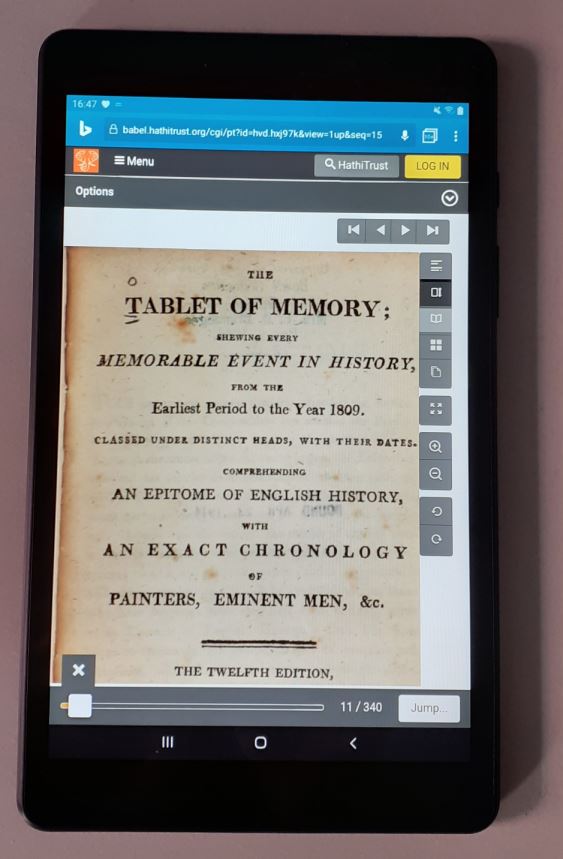

The oldest item in my book collection dates from 1809. It is small volume with 314 pages of minuscule type entitled The Tablet of Memory. The early nineteenth century being an age of grandiloquent book titles, its full name naturally fills most of a page:

The Tablet of Memory;

Shewing Every Memorable Event in History,

from the

Earliest Period to the Year 1809.

Classed under distinct heads, with their dates.

Comprehending

An Epitome of English History with an Exact Chronology

of Painters, Eminent Men, &c.

It is the twelfth edition (“with corrections, alterations, and improvements”), printed in London in 1809 by what is the longest publisher details I think that I have ever seen: “Printed for J. Johnson, J. Walker, Wilkie and Robinson, G. Robinson, Scatcherd and Letterman, Darton and Harvey, J. Brooker, Lackington, Allen and Co. Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, and J. Asperne”.

I can’t remember where I came across the book, only that it was modestly priced, and I was intrigued by its dense compilation of facts. It was clearly a popular title in its day. I’ve not been able to work out when the first edition was published, but it was probably in the late 1760s – the third edition was printed in 1774, the fourth in 1778, and editions kept roughly to that three-to-four year pattern thereafter. Its original printer and editor may have been Philip Luckombe, whose name is on the 8th to the 10th editions. He died in 1803. No editor is credited for the 1809 edition, but much of it remains Luckombe’s work. There were other ‘Tablet of Memory’ titles produced around the same time – The Tablet of Memory; or, the Historian’s Assistant (1773), Edward Cork’s Remembrancer; or, Tablet of Memory (1792), The Tablet of Memory; or, Historian’s Guide (edited in 1792 by the Rev. John Trusler, continued maybe to 1812), The New Tablet of Memory (a variant of Luckombe’s title, 1807 onwards), Mnemonika; or, The Tablet of Memory (1829), and others – but my title, seemingly anonymously compiled, was the market leader, the others opportunistic imitations. ‘The Tablet of Memory’ was not just a publication title, but a common phrase, denoting a particular kind of reference work and the assemblage of information.

The introduction to the 1809 Tablet of Memory boasts of the compendium’s great success. The editor, we are told, has selected information from “historians of the first rank, as well as the most authentic annalists”. Whether these historians and annalists were commissioned or merely copied is not divulged, though the latter seems most likely. The editor sets out the value of the compendium:

It will save the learned the trouble of turning over voluminous authors to refresh their memories; to the enquiring mind it will give information; and to the ignorant it will convey instruction. It will be a remembrance to those who have forgotten what they have read, and may serve as an Epitome of English History. Care has been taken to reconcile the groundless jars of annalists and historians, who often conceal truth, and mangle probability.

The book divides the essential knowledge that it promises into assorted categories, each ordered alphabetically or chronologically. The contents listing includes Remarkable Occurrences, Phenomena, &c.; Memorable Events; Accidents, Earthquakes, Famines, Fires, Frosts, Inundations, Storms, Tempests, &c.; Improvements, Inventions, Discoveries in Arts, &c.; Discoveries and settling of Countries; Kingdoms, States, Cities, Towns, &c. funded; and many short sections listing sovereigns, universities, companies, religions, laws and more, concluding with Battles, Sea Fights, Sieges, &c.

There are such riches within. One recognises the familiar, but what entrances are those names, discoveries and calamities now long forgotten, but reckoned worthy of remembrance in 1809:

Swearing, the vice of, introduced, 1072

Dedications to books introduced to get money, 1600

Straw used for the king’s bed, 1234

Ale invented, 1404, B.C.; Ale-booths set up in England, 728, and laws passed for their regulation

Burning alive on account of religious principles, the first was Sir William Sawtree, Feb. 19, 1401

Andover, Lord, killed while delivering his fowling-piece to the servant, Jan. 8, 1791

Mechanical Arts in Britain in greater perfection than in Gaul, 298

Scaffold, a, built for spectators to see Lord Lovat beheaded fell down, and several persons killed, and a great number maimed, 1747

Sampson pulled down the temple of Dagon, and destroyed 3000 Philistines, 1117 before Christ

English parents forbidden by law from selling their children out of the kingdom, 1000

Tea-dealers obliged to have sign-boards painted, 1779

Knitting stockings invented in Spain about 1550

Column of fire appeared in the air at Rome, 30 days, 390

Urine – the inhabitants of London and Westminster, &c., commanded by proclamation to keep all their urine, throughout the year, for making salt-petre, 1626

Anchors invented, 587

Artichokes first planted in England, 1487

Lightning, a flash of, penetrated the theatre at Venice, during the representation; 600 people were in the house, several of whom were killed; it put out the candles; melted a lady’s gold watch-case; the jewels in the ears of others, which were compositions, and split several diamonds, Aug. 1769

Lanterns invented by King Alfred, 890

Powell, a lawyer, walked from London to York and back again in six days, Nov. 27, 1773; above 402 miles; again June 20, 1788, when aged 57

Books in the present form were invented by Attalus King of Pergamus, 887

Bosia, the village of, at Piedmont, near Turin, suddenly sunk, together with above 200 of its inhabitants, April 8, 1679

Candle-light first introduced into churches, 274

Abstinence, remarkable instance of, in Ann Moor of Tutbury, Staffordshire, who has lived 20 months without food, Nov. 1808

Promotheus struck fire from flints, about 1715 before Christ; he being the first person, is said to have stolen it from Heaven

Stops in literature introduced, 1520; the colon, 1580; semicolon, 1599

Treason requiring two witnesses, 1552

This is a rich mix of the historical and the mythical, the weighty and the inconsequential. It is from a time when Bishop Ussher’s literal reading of the Bible, in which the Creation was confidently dated at 4044 B.C. (an occurrence curiously omitted from The Tablet of Memory‘s section on ‘Memorable Events’). It betrays a determination to pinpoint everything to a year, because every phenomenon must have had a starting point. It is decidedly shaky when it comes to historical accuracy, with wrong dates, attributions and interpretations throughout. No sources are given, of course. What is presented as fact becomes its own justification.

Not all of the entries are so pithy. There are long sections on Conspiracies, Fires, Frosts, Inundations, Massacres, Riots, Storms, and a singularly upsetting one on Jews, which takes every fanciful record of atrocities perpetrated by Jews, and the rather more credible atrocities perpetrated against them, that the editor could find. One sees a world continually visited by calamities, as part of the natural order of things, and because a tablet of memory must record the extraordinary, never the ordinary, to which dates seldom apply. Here is the entry on Plagues:

Plague—the whole world visited by one, 767 before Christ; in Rome, when 10,000 persons died in a day, 78; in England, 762; in Chichester, when a 4,000 died, 1772; in Canterbury, 788; in Scotland, which swept away 40,000 inhabitants, 954; in England, 1025, 1247, and 1847; in England, when 50,000 died in London, 1500 in Leicester, &c.; in Germany, which cut off 90,000 people, 1848; in Paris and London very dread ful, 1867; again 1879; in London, which killed 30,000 per sons, 1407; again, when more were destroyed than in 15 years’ war before, 1477; again, when 30,000 died in London, 1499; again, 1548; again 1594; which carried off in London a fourth part of its inhabitants, 1604; at Constantinople, when 200,000 persons died, 1611; at London, when 35,417 died, 1625 and 1631; at Lyons, in Prance, died 60,000, 1632; again at London, which destroyed 68,000 persons, in 1565; at Messina, Feb. 1743; at Algiers, 1755; in Persia, when 80,000 persons perished at Bassorah, 1773; at Smyrna, that carried off about 20,000 inhabitants, 1724; and at Tunis, 32,000, 1724; in the Levant, 1726; at Alexandria, Sumyrna, &c. 1791; in Egypt, in 1792, where near 800,000 died; the yellow fever destroyed 2000 at Philadelphia, in 1793; on the coast of Africa, particularly at Barbary, 3000 died daily; at Fez, 247,000 died, in June, 1799; 1200 died at Morocco, in 1800, in one day; in Spain and at Gibraltar, where great numbers died in 1804 and 1805.

Plagues, ten of Egypt, 1404 before Christ.

There is usually disdain expressed towards the reduction of history to dates, or the mere assemblage of facts (or pseudo-facts) over an understanding of the past as being formed by complex forces. Dates are for pubs and TV quizzes. They cannot confer understanding.

Yet I have always cherished such publications. For many years, before the Internet brought such information to us at the touch of a button, I returned again and again to such cast-iron reference sources as Neville Williams’ Chronology of the Modern World, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, The Guinness Book of Answers and the annual volumes of Whittaker’s Almanack. Such works, far more reliable than The Tablet of Memory, of course, were not just a quick reference source but an encouragement to discovery – each entry opened up a world. They also gave you a sense of their times, of what was important, and what – through omission – had been marginalised. They were profoundly determined by the ideologies of their times, but that was what could be so illuminating about them. To recognise gaps in, say, the history of women or ethnic minorities, was an encouragement to fill in those gaps. Equally, I used Whittaker’s Almanack religiously when starting my first proper research project, on early newsreels, because of its unerring sense of what was viewed as significant in each year. They helped me understand news history from the perspective of the times, not merely from the perspective of mine.

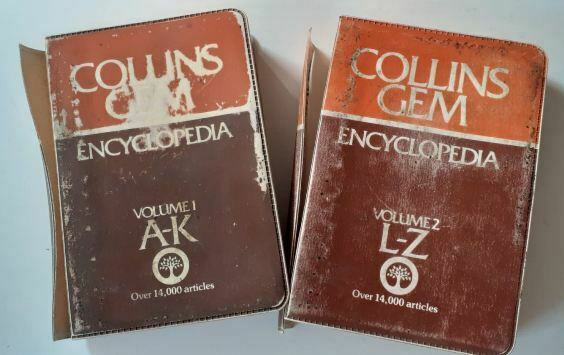

Most valued among these reference works was my own ‘tablet of memory’, the Collins Gem Encyclopedia (first published 1979), with 14,000 articles crammed into two volumes smaller than my hand. The volumes, which I still have, show how fervently and regularly they were used, with their battered covers, loose spines, and page edges stained deep-brown with finger grime.

At a time when I needed to soak up all the knowledge that I could, the Collins Gem was my friend. Time and again it offered a concise summary of names, events and phenomena that steered me forward. And I’m still using it – only the other day I needed a clear summary of the Crimean War (to help me write one of my own). All of the war histories I had to hand, Wikipedia and other online sources failed me. Collins had this:

Crimean War (1853-6), conflict between Russia and Britain, France and Turkey. General cause was Anglo-Russian dispute, esp. over control of Dardanelles. Pretext was Russian-French quarrel over guardianship of Palestinian holy places. Turkey’s rejection of Russian territ. demands prompted latter’s occupation of Moldavia and Walachia. Turkey declared war (1853), France and Britain joined (1854), Sardinia (1855). Main campaign, centring on siege of SEVASTOPOL, in Crimea, was marked by futile gallantry (eg charge of the Light Brigade at battle of BALAKLAVA) and heavy casualties; hospital work by FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE. Settlement at Congress of Paris checked Russian influence in SE Europe.

What more could you want? Plus those capitalised cross-references directing you to look further. Later you could read the histories, but for now you had what you needed to know, and knew where to go. Dates and summaries create maps for the mind.

Key also to the success of that encyclopedia was its size. It was human-sized; it matched the size of your hand. It could be easily carried, it could fit in anywhere, it used up no space at all. It became a part of you. This is, of course, what is fundamental to the success of the book – it can be held in a hand (palm and three fingers to keep it steady, thumb and little finger to hold down the pages on either side). Of course there are books that are too large to held held in the hand (including many reference books). There is something about this that diminishes their value as books. They have the information but they do not have the human connection.

This was evidently part of The Tablet of Memory‘s great success. It belonged to the hand, any hand (“from the throne to the homely cot”, as the book’s preface has it). Knowledge could be in the hands of anyone. Its size affirmed its democratic purpose.

Today, I have a different tablet of memory. It is electronic, it comes with apps, it links me to a world of knowledge – as ideologically constrained as ever was the case in 1809, yet infinitely more various in application. It too is hand-sized, or thereabouts. It too makes me knowledgeable, not simply in what it enables me to discover but in its size. As with my smartphone, it is a hand-borne extension of thought, and so an extension of myself. Those who decry an age when everyone is on their phones, apparently missing the world around them, not only fail to understand phones, but fail to understand books, or any means of the transference of knowledge. They fit into ourselves, and through that recognition and trust we learn from them. The Tablet of Memory now runs into a infinite number of editions, but the measure remains the same.

Links:

- The twelfth (1809) edition of The Tablet of Memory, original held by Harvard University, is available on the HathiTrust Digital Library

I have a copy of the third edition 1774 of the Tablet of Memory

It’s good to know of other copies out there. Does your edition give the name of a printer?

Thank you for your article! I just came across one of these books- from 1807 which is the 11th edition. It says it was printed by E. Hemsted, Great New Street, Fetter Lane.

Thank you – one day I must produce a list of all the editions and who printed them, as an appendix to this piece.