I was spending two weeks in the Lake District, and I wanted to seek out one of the lakes I had not seen before, despite having visited the area many times. Ennerdale Water is one of the least known and least visited of the lakes, owing to its remote location to the west of the area, far from any main road. No public transport goes near the lake, so – having no other means of transportation available to me, and being based in the central town of Keswick – my only option was to walk.

It was too far off for me to walk there and back in a day, but getting there was just about manageable if I started from Buttermere, a peak or two on the other side of Keswick. Taking the bus to Buttermere village, I passed along the strip of land that separates Buttermere and its companion lake Crummock Water, turned left, then climbed up alongside Scale Beck, taking time to see the celebrated waterfall Scale Force, before heading west along a boggy pass between the peaks of Hen Comb and Starling Dodd.

It was midway on this journey, with bare peaks all around that I thought, I am in the middle of nowhere. There were no distinguishing features on any of the slopes about me. The path had disappeared into the wet, the sheep that had I had been coming across were all gone, and no birds sang. The silence was absolute. I looked on the map. There was no name for the place in which I found myself. I was nowhere. I had the most peculiar thought of simply lying down where I was and stopping, understanding that I would be never discovered. My corpse would just sink slowly into the bog, unmarked and unmapped.

The phrase ‘the middle of nowhere’ is an odd one. One cannot be on the edge of nowhere, because to be in such a place you would have to be aware of, or have sight of, somewhere. Nowhere either has no middle, or else middle is all that it has. It has to be an absence, like a vacuum. Nowhere is where the maps have failed, where the way in and the way out can no longer be made out. Nowhere exists to remind us that without place we are no one.

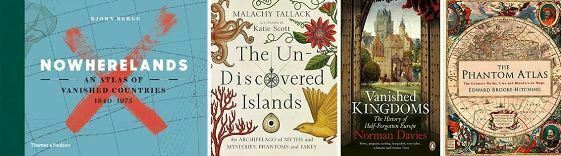

There seems to be a growing interest in places that do not exist, so are consequently nowhere, if publishing trends are something to go by. Bjørn Berge’s Nowherelands: An Atlas of Vanished Countries 1840-1975 is a gazetteer of places that exist once but are no more. The author has selected the places because, however small or however briefly in existence, they found time to issue stamps. This is also the idea behind Stuart Laycock’s Lost Countries: Exotic Tales from an Old Stamp Album. Both are fascinated by places whose historical outline vanished even though the geography remains. We define ourselves by lines, but what real meaning is there in a line?

This sort of thinking lies behind Norman Davies’ Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe, a weighty history of kingdoms, empires and republics that once were and are no more: Aragon, Burgundia, Galicia, Sabaudia, Tolosa and the CCCP, among many others, territories whose vanished status should remind us that all boundaries are arbitrary, time-limited, and ultimately imaginary. Everywhere that we think of as somewhere will one day be nowhere.

Some places never existed at all, and yet some of us believe in them, though we may struggle to locate them on any map. Malachy Tallack’s The Un-Discovered Islands: An Archipelago of Myths and Mysteries, Phantoms and Fakes is an entrancing account, enhanced by Katie Scott’s dreamy illustrations, of mythical places that one would have to sail forever before finding them: Thule, Lemuria, Hy Brasil, the Island of the Seven Cities, Atlantis. If Tallack’s book documents places of dreams and aspirations, Edward Brooke-Hitching’s The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps takes a harsher view. He traces a history of mendacity and delusions, from fake mountain ranges to fake peoples, all documented at the time in maps and atlases to a confer a reality on imaginary places with the hopes of pleasing kings or defrauding investors.

But one can treat this urge towards places that never were in a more kindly light. Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi’s classic reference work The Dictionary of Imaginary Places documents places found only in fictional works, from the Country of the Blind to Laputa, from Macondo to Oz, from Eldorado to Never-Never Land, each described with a geographical passion and seriousness.

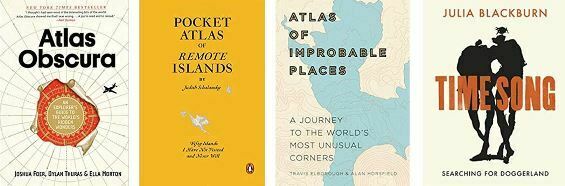

Indeed, our passion for places is unconstrained by geographical or historical reality. Books about ‘nowherelands’ are part of a publishing trend that provides guides to places that we can hardly believe exist now, and yet they do. Atlas Obscura: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders, a guide to fantastical destinations in remote locations, is probably the leading example, but there is also Travis Elborough and Alan Horsfield’s Atlas of Improbable Places: A Journey to the World’s Most Unusual Corners, or Alastair Bonnett’s Off the Map: Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands, Feral Places and What They Tell Us About the World.

Or there are those places whose geography was changed not by politics but by climate. Julia Blackburn’s recent Time Song: Searching for Doggerland is a lament for a land – that which once connected the east of England to mainland Europe, but which now lies under the sea, a true Atlantis. Other lands may become nowherelands through rising waters, and all too soon.

Such works, whether about places true or imaginary, discoverable or lost, appeal to the wishful traveller in us all. Judith Schalansky’s Pocket Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Not Visited and Never Will gets to the nub of it. The author takes us on a journey to remote places that she has no hope of seeing, except that the hope lies in the imagining. Unattainable places become places of fantasy, and imaginary travel of greater value – certainly of greater practicality – than the travel options open to the majority of us.

We want to be explorers, or to know that there remain places to be explored. The more we know of each corner of the globe, sighing at the pretensions of those who claim to be explorers in the mould of Livingstone, Shackleton, Thesiger or whoever, when every great challenge that the earth has presented now seems to have been met, the more we yearn for the unknown. We need the hope of discovery, the paradoxical assurance that we do not know everything. To know every corner is to lose imagination, even to lose hope. If we know everywhere, the reality may turn out to be that we are nowhere, for there will be no reason or purpose in looking. So we must keep on discovering, and keep on producing maps, whether real or imaginary, present or past.

I carried on with my journey. The isolation was accentuated all the more by the high, plain peaks all about me, shutting out any sight or sense of out an outside world. But I proceeded steadily up the slope at the end of the valley, following the line of a stream, passing by an isolated tarn, climbing still further, til I came to the lip of the land. There I was faced with the most extraordinary sight. Absence was replaced in an instant by the panorama of western Cumbria, with towns and roads and fields (some bright yellow with rapeseed) and beyond the sea, the sea. It was shocking and exhilarating, from being nowhere to seeing everywhere.

I came down the hillside. Progressively my destination came into view, Ennerdale Water, a beautiful lake, eerily quiet. It felt remote, but it was somewhere. I had made my discovery.