It was the day after the United Kingdom left the European Union (for the time being), and I went to London’s centre for Italian art, the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art. The Estorick is one of the most pleasing art galleries in the city; small, to be sure, but greatly charming, and always big enough for an adventure. It is based in a beautiful Georgian house off Canonbury Square in Islington. Previously it was known as Northampton Lodge, and was for a time the offices of the architect Colin St John Wilson. It was within these walls that he designed the British Library, my workplace. So I feel that I have just that extra degree of affinity with the place.

In 1994 it was acquired by the Eric and Salome Estorick Foundation as a home for the couple’s collection of Italian modern art. When you visit, you are very much aware of its genteel domestic past. The corridors are narrow, the bends in the stairs tight, the rooms are still very much rooms. It is, in a deep sense, a home for art.

The gallery stretches over three floors with six gallery rooms. The ground floor shows changing exhibitions, with the upper floors tending to display fixed treasures from the collection. The Futurists, those artists who followed Filippo Marinetti in embracing dynamism and the machine age, wrote lots of manifestos, and became (some of them) attracted rather too much to Fascism, feature strongly.

It was one of the Futurists that I came to see, though I knew nothing of him beforehand. Tullio Crali (1910-2000) was was late in joining the movement, being younger than the first wave and not joining up until 1929, but he became one if its most ardent adherents. He specialised in ‘Aeropittura‘, a peculiar enthusiasm of the Futurists – paintings which celebrated aeroplane as a symbol of all that the movement was about. In Crali’s case this meant works that veered from the dazzlingly multi-layered (he was especially good at portraying complex cockpit views of the land and sky) to near-kitsch. He carried on the cause of Futurism after Marinetti’s death in 1944, virtually single-handed, continuing to produce paintings in what was now an old style, adamant that Futurism and its aesthetic were timeless.

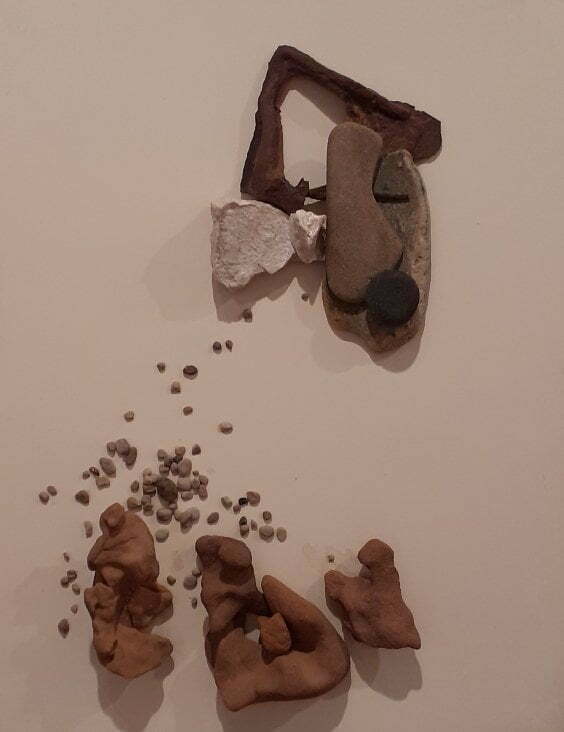

But what struck me were not his bold paintings of air, speed and machinery, but his works with stone. On an upper gallery, across one wall, there are some truly startling examples of what Crali dubbed ‘Sassintesi‘ (stone syntheses). They instantly strike one with the shock of originality.

In 1959 Crali discovered working with natural materials, specifically rocks and stones, with the occasional iron. Naturally he wrote a manifesto about it. He argued that this was a new art form, not just in its materiality, but in how its creation occurred through a combination of chance and selection:The results have some affinity with collages, but collages work because they find new meaning in the reassembly of discarded man-made objects. Sassintesi aim to reveal the overlooked interrelationships between natural things.

Sassintesi should not be confused with painting or sculpture. It is another language, different to these in both substance and expression. Matter is added to colour and form, playing a dominant and decisive role. Like the two other elements, matter has its own sympathies and antipathies – its own harmonies and clashes – which must be intuited and evaluated. Here, however, colour, form and matter are not created by the artist, who instead discovers them in the pieces that he seeks, selects, combines and organises in the manner that most closely conforms to his conception, like a director.

Despite Crali’s claims, his Sassintesi look every bit as studied in their final form as any other kind of artwork that starts with raw materials (sketches, daubs, a raw rock from which a sculpture will emerge). Instead it is their superficial similarity to other artforms that gives them their revolutionary power.

What is so striking about them is that the found material are arranged on canvasses and hung vertically. One is familiar with artworks using found media that arrange them on a flat surface, or where they were found naturally, or those mixed media works that bland natural materials with paint to create something peculiarly organic in tone. But Crali’s Sassintesi are stuck starkly to a canvas, looking like a painting and looking nothing like a painting at the same time. Their strength lies in how they challenge ideas of how art is composed and portrayed. They defy our expectations as they defy gravity.

They are singularly beautiful. They are distinguished by great judgment on the artist’s part, who makes sparing arrangements particularly telling. The limited palette of greys and browns contributes as much to the harmony as does the combination of ragged and smooth objects. They tell no stories (some come with titles – ‘Aerolandscape’, ‘Future Fossil of the Mechanical Civilisation’, ‘Return from the Crusades’ – which might have been better ignored). Or rather they suggest that pure matter can so arrange itself to reveal the nature of things, which the artist may intuit if never entirely understand. They may be saying simply that ultimately all art fails, because we fail.

What I also found compelling was their arrangement across a wall. Artworks only exist in context; they have to be shown somewhere. They are as much a product of their arrangement as their creation. And there is something powerful about a wall given over to make a statement. It fully occupies the eye, mimicking the horizon. The wall is a canvas in itself, with found objects that the curator will seek, select, combine and organise in the manner that most closely conforms to their conception.

Art cannot fail. It frames everything.

Links:

- ‘Tullio Crali: A Futurist Life‘ continues at the Estorick until 11 April 2020

- There is a Tullio Crali website, www.tulliocrali.com (in Italian), with striking displays of his artworks, including a section on Sassintesi