If you visit the Lake District, there is one name in particular that is both omnipresent and yet almost completely invisible. There is much that promotes, celebrates or otherwise exploits the names of Wordsworth, Potter, Coleridge, Wainwright, but what of Rawnsley? What visitor to the Lakes knows of him. Yet go the central town of Keswick and you will see the Rawnsley centre, find a plaque on the path leading to Derwentwater commenorating the name, and at Crosthwaite church on the edge of town find a tomb and a memorial to the man, Hardwicke Rawnsley. Memorials exist elsewhere – there is a prominent plaque in Carlisle cathedral, where he was a canon, while his many books of Lakeland lore and poetry have whole shelves to themselves in the second-hand bookshops (while they have been long absent from the first-hand stores).

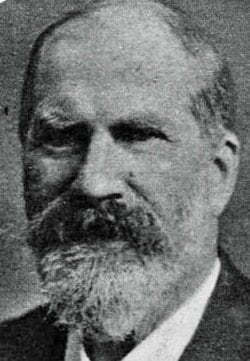

Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851-1920) was one of the most significant shapers of modern life in this country. Together with Olivia Hill and Robert Hunter, he founded the National Trust in 1895, for which body he was for many years its secretary and the driving force behind its early fundraising and land purchase successes. He started out as an ordinary vicar, posted to Wray church in Windermere in 1878, before moving to Crosthwaite near Keswick in 1883. Through prodigious energy, good connections and a passion for causes, he showed how one could make the most of being located on the fringes of a country through sheer force of personality.

It is thanks to Rawnsley and his National Trust colleagues that the nation has ownership of Brandlehow Wood, much of Borrowdale, Castlerigg stone circle, Friar’s Crag (where Rawnsley was instrumental in setting up a cross in memory of his university friend John Ruskin), Lords Island and other iconic Lake District locations. He purchased Greta Hall in Keswick, where Coleridge and Southey lived, and later Allan Bank in Grasmere, which was Wordsworth’s final home and became Rawnsley’s final home also. He left it to the National Trust. He made a particular impact through his campaigning zeal in halting the further encroachment of railway lines in the area (his first great success was preventing the building of a line between Buttermere and Keswick, in 1883). He could be pragmatic in the face of progress, however – having campaigned fiercely against the creation of the artificial lake Thirlmere as a reservoir (which involved the flooding a hamlet and several farms, as well as the swallowing up of the two small lakes that had been there previously), he stood down from the battle, attended the opening ceremony and praised where he felt praise was due.

I’ve long had an interest in Rawnsley for three reasons in particular. The first is his role is helping to preserve the Lake District as now have it, blending zeal with pragmatism. The second is poetry. Rawnsley was a phenomenally productive writer, writing guide books, tracts, Wordsworthiana and countless lobbying letters, but it is poetic output that stretches credibility. He is said to have composed over 30,000 sonnets. I don’t know how many were published, though he produced many volumes of poetry and submitted poems regularly to the newspapers, at a time when poems that provided comment on the issues of the day provided welcome copy, but 30,000 sounds beyond possibility. But Rawnsley somewhere said that he composed a poem or two almost every day, poetry being for him as way of collecting his thoughts. He wrote his first poems as a child, but if you just take his fifty years of adult life, multiply that by 365, and you have 18,250 days. A poem or two each day, just as mental exercise – he could have done it. It’s unlikely, and if so the vast majority went unpublished (he produced over forty books, but not all of them verse), but I think it’s just meant to be a big number, maybe indeed deduced from his writing habits.

Were they any good? Well, no. Those I have read are commonplace in thought and expression, invoking inspiration while seldom demonstrating it. They champion religion, country, empire, tradition and landscape. Many comment on recent events – his 1906 collection A Sonnet Chronicle, 1900-1906 has poems on the passing of the century, the deaths of Queen Victoria, Cecil Rhodes and Emile Zola, the coronation of Edward VII, the Delhi Durbar, entente cordiale, and the Russo-Japanese War. But there is occasionally some feeling there – here, for example, in ‘The Skiddaw Bonfire‘ (on witnessing a bonfire lit on top of Skiddaw mountain in the Lake District to mark the coronation of King Edward VII):

The Skiddaw Bonfire

0n the Evening of June 26th, 1902.

Here dumb I stand who had so much to say,

Whose heart would be so warm, here stand I cold;

The lingering sun beneath the verge has rolled,

And the long, mellow twilight melts away.

I, who was meant so well to end the day

Of national triumph, sorrowful I hold

Dark commune with dark Skiddaw—fold on fold,

With plains unlit by diamond-bright inlay.

But, tho’ the great stars visit me in turn

To mock me in my grief, I have no shame,

I watch and wait for good that is to be;

The day will dawn whose night has need of me,

My heart shall yet with exultation burn,

And the King’s crowning call from flame to flame.

The only piece of Rawnsley poetry that is known today, and is in print, is that which was never published at the time – his version of his friend Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, which he adapted into verse, with her drawings, when she was seeking a publisher (“There were four little bunnies / no bunnies were sweeter / Mopsy and Cotton-tail,/ Flopsy and Peter”). Frederick Warne & Co. eventually agreed to publish, on one condition – that Potter’s original text was used, not Rawnsley’s.

But though his poetry was indifferent at best, all too often plain bad, that is not the point. His thoughts were sonnets. It shows an extraordinary cast of mind, one that had always to be composing, that appreciated the underlying rhythm of things.

The third reason for my interest in Rawnsley, and indeed why I first encountered him and wondered who this turbulent priest could be, was his campaign against the cinema. It was in 1913 that Rawnsley produced a pamphlet, The Child and the Cinematograph Show and the Picture Post-Card Evil, which immediately made him one of the leading voices critical of the new medium. It is probably not coincidental that 1913 was the year when the Keswick Alhambra Theatre Company was formed, for the purpose of exhibiting motion pictures in the town. The Alhambra cinema, Keswick’s first, opened in January 1914 – and continues to this day.

Rawnsley aimed his ire at the cinema’s facility for visualising the horrific, emphasizing the impact upon children:

There appears to be passing over the land a real craving for scenes of horror … It is not improbable that the cinematograph film has a good deal to answer for in this matter of the public demand for horror and sensation. On many of the hoardings near the cinematograph halls or pavilions, beneath the sensational programmes are written such words as “nerve-thrillers”, “eye-openers tonight”, and when we turn to these programmes we cannot help noticing that it is the horrible that draws. “Massacre; a terrible tragedy, 2000 feet”; “The Wheel of Destruction”; “The Motor Car Race: the car when going at prodigious speed overturns and buries its living occupants. Don’t miss this”. “Dante’s hell”, the Devil film, with a huge invitation beneath it, “Don’t miss this opportunity of seeing Satan – Satan and the Creator; Satan and the Saviour, 4000 feet in length”; all these are signs of a downgrade pandering to a sense of horror which is being fostered throughout the length and breadth of the land by the downgrade film.

I spoke to a boy, about twelve years old, who had attended a cinematograph show in a little country town a week or two ago, and he positively trembled as he reported what he had seen. He said, “I shall never go again. It was horrible”. I said, “What was horrible?” He said, “I saw a man cut his throat”.

As I write, a friend tells me that a week or two ago his neighbours, seeing pictures of Sarah Bernhardt advertised as the chief item in a cinematograph show, visited the hall with their little daughter. They found to their disgust the bulk of the entertainment was sensational horrors of such a character that in consequence they were obliged to sit up all night with the child, who constantly woke with screams and cries …

Nor is this sense of horror alone appealed to. Many of these films prove to be direct incentives to crime. Clever burglaries are exhibited before the eyes of mischievous boys, who at once have their attention called to the possibility of the “expert cracksman’s life”.

These were common arguments, as society’s guardians reacted with alarm and not a little incomprehension to a medium that was proving so popular with children. It was fear not of the horrific but of the unknown, and so the uncontainable. That such alarm was not universally shared is revealed in this passage, where Rawnsley is worried that officialdom is not always viewing the cinema with the same degree of alarm that he felt.

The worst of it all is, that neither the police nor the agents of the cinematograph firms who are sent out as exhibitors, are sufficiently educated to know what is horrible and what is not. Thus, for example, when the mayor was appealed to in a town where the most terrible exhibition of the horrors of hell and the tortures of the damned were being visibly enacted as illustrations in gross caricature of Dante’s Inferno, he in turn appealed to the police to visit the cinematograph hall and report. The officer who was well up in the legal aspect of the case and was probably on the look-out for a criminally indecent film as a thing to be objected to, reported to the mayor that he could see nothing objectionable in this horrible Hell film, and therefore had not thought it necessary to speak to the exhibitor.

There other interesting fears expressed when it comes to religion. In this passage Rawnsley is complaining, not unreasonably given his profession, over the commercialisation of the divine (the film to which he is referring appears to be is Sidney Olcott’s 1912 feature, From the Manager to the Cross, which was filmed in Palestine), but comes close to to recognising that film can render the supposedly mysterious as absurd.

It is not only the sensational, cruel, or crime film that is sowing seeds of corruption among the people. The film manufacturers have invaded the most holy mysteries of our religious faith. There can be no question that in suitable surroundings, and with specially reverent treatment, pictures from the life of our Lord may be impressive and educational, but the idea of exploiting the life of our Lord as a commercial speculation, and the getting of a troupe of actors to go out to Palestine and pose in situ as His disciples, and as impersonators of the scenes described in the Gospels, is in itself abhorrent; and the quickness of motion needed by the film takes away reverence and imparts a sense of what is artificial, and sometimes almost comic.

However, having made this strong intervention in the debate around cinema and society, though he followed it up with some letters to the national newspapers, Rawnsley seems to have been silent on the topic thereafter. Perhaps the formation of the British Board of Film Censors in 1912 dulled his impact. Perhaps it was simply that he was getting old, or had taken on too many campaigns. He was a Victorian, from an age when people listened to vicars with time on their hands, but cinema was of another age. It was so much easier to block a railway line than to block what went on in someone’s head.

Were Rawnsley around today, there would be plenty to occupy him. Current controversies in the Lake District include plans to introduce zip wire entertainments and houseboats on Grasmere. One senses him spinning with fury in his Crosthwaite grave. The best thing about him was that he was not a nostalgist fighting against any change to the Eden that was the Lake District – so not like William Wordsworth, for instance, who became apoplectic simply over the new taste for painting the outside walls of houses white. Rawnsley wanted preservation, not prevention – at least as far as landscape and buildings were concerned. It is the recognition of the need to balance change with the saving of that which would be of greatest value to the public, that was his great bequest to the National Trust.

One can even imagine him campaigning to ensure the Alhambra’s survival.

Links:

- There is a very good website, Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851-1920), produced by his great-granddaughter Rosalind Rawnsley, which though still under construction, is full of rich and interesting detail based on good understanding and fresh research

- Hunter Davies’s article for The Independent, ‘Rawnsley! Thou shouldst be living at this hour‘, is an engaging summary of Rawnsley’s life and passions (“his interests and campaigns expanded to a national level, and many of them now seem astoundingly modern: against pollution in streams; pro- organic farming; up with pure milk; down with white bread”)

- The Child and the Cinematograph Show, as published in The Hibbert Journal, vol. xi. (1912-1913), is available on the Internet Archive

- There’s a history of the Alhambra in Keswick on its website. It has been in continuous operation for over 100 years, and does not look like it has changed much (a successful 2019 crowdfunded restoration brought back much of the original colour scheme – see this lovely promotional video https://vimeo.com/361599390). It is my favourite cinema.