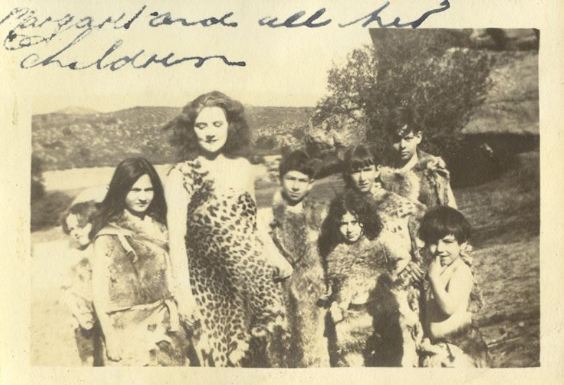

The first feature film that Buster Keaton directed, The Three Ages, is not perhaps as familiar as it should be. A comic history of love in prehistoric, Roman and modern times, it has Keaton fighting his rival, Wallace Beery, over a girl and winning her against the odds each time. Allegedly parodying Intolerance, it is really three sketches strung together rather than a true feature, but it is still highly amusing (especially in the Stone Age sequence) and boasts some breathtaking stunts. The actress playing the girl is Margaret Leahy, and it was her only film. While researching the history of a British newsreel, I came across the extraordinary events which led this Brixton shop girl to be Keaton’s co-star.

Film star competitions were a particular feature of the silent era; that is, competitions run by newspapers or film magazines for which the prize was to appear in pictures yourself. There were standard beauty competitions where the winner sometimes ended up with a film contract later, there were cinema beauty competitions where the contestants were filmed and then judged by the audience, but competitions that offered directly for the winner to become a film star were something special. In such competitions, newspapers, fan magazines and film companies exploited audience dreams of film stardom with promises of screen tests or parts in forthcoming films. The film companies found this useful publicity for forthcoming productions and may have even hoped to find some future star in this way.

In America, such contests were sufficiently common for them to be made the subject of at least two major feature films. In The Extra Girl (1923), Mabel Normand plays a competition winner who finds that her prize of a job in the movies actually means working in the wardrobe department; in Ella Cinders (1926), Colleen Moore is a down-trodden Cinderella figure who wins a competition and ends up in Hollywood. Both, needless to say, after some trials and tribulations, find themselves becoming true film stars. The dream for Cinderella could, in any case, sometimes come true. By far the best known winner of any film star competition is Clara Bow, who began her career with a bit part as the prize for winning a fan magazine beauty competition. Bow was blessed with a talent significantly lacking in most other film star competition winners, most of whom returned swiftly to obscurity.

In Britain film star competitions sprang up in the immediate post-war period. In 1919 the Sunday Express newspaper, in association with the Stoll Film Company, organised a nation-wide contest, won by Miss Tommy Sinclair, who it was said would be found a ‘suitable part in a Stoll production’, though if this were so it was only a bit part. In the same year a more widely publicised contest was organised by the Daily Mirror newspaper and the Samuelson film company, won by Miriam Sabbage, whose picture was featured prominently in advertising for the feature film in which she got third billing, The Bridal Chair. The trade paper The Bioscope in reviewing the film noted accurately that

it may be questioned whether, from a strictly artistic point of view, prize-winning beauty is in itself a sufficient qualification for the creation of a new film star, but there can be no doubt that it is a sound commercial proposition. Everyone will want to see the beautiful Miss Sabbage, and she will be found in ‘The Bridal Chair’ large as life.

Her on-screen career was to progress no further, but off-screen she did marry the cinematographer.

Pathé held a ‘Screen Beauty Competition’ in 1920, and in 1921 Gaumont organised a contest they called ‘The Golden Apple Challenge’, for which a reported 26,700 contestants entered for a prize of £500 and a promised film contract, with the most promising contestants featured in a ‘women-only’ serial set in a detective agency. Winifred Nelson, the eventual winner, did get to appear in minor roles in two Gaumont features. Stoll Film Studios returned to beauty competitions in 1925 with its ‘Starlings of the Screen’ contest. This was won by Sybil Rhoda, who appeared in three subsequent feature films, including a creditable performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s Downhill (1927). And at the end of the silent era, Molly Lamont became a minor star in British and American films for twenty years after winning a competition in 1930 in a South African newspaper.

But minor parts in British feature films were no match for a starring role in a major Hollywood film, which is what was offered by the Daily Sketch newspaper in 1922, when they organised the grandest and most widely publicised film star competition of them all. The genesis of the idea came from the American company First National Pictures, with their two leading stars, the immensely popular Norma and Constance Talmadge. Joe Schenck, chairman of First National and Norma Talmadge’s husband, probably proposed the idea, but at the encouragement of Sir Edward Hulton, a British newspaper owner with interests in the cinema. Hulton ran a newsreel, the Topical Budget, and the film distributors Film Booking Offices (F.B.O., not to be confused with the American distributor of the same name), as well as the popular newspapers the Daily Sketch and the Evening Standard. F.B.O. handled major American features in Britain (e.g. Broken Blossoms, Blind Husbands), and the impetus for a competition to find a British film star probably came from Hulton’s contacts and interests, since the Talmadges might have welcomed, but hardly needed such a publicity stunt.

The competition was to find a British actress to play second lead in Norma Talmadge’s forthcoming film Within the Law. Beauty competitions would be organised on a regional basis, with entrants and winners featured regularly in the Daily Sketch and the Topical Budget. The final one hundred contestants would then be screen-tested and Norma and Constance Talmadge themselves would come to Stoll Film Studios (where the screen tests were to be made) and select the winner. First National would also have the latest Constance Talmadge film, East is West, on release that week. The winner would then be taken to Hollywood to appear in Within the Law, and would be groomed as a British film star. It was marvellous publicity for the Talmadges, First National and Hulton; the hapless British film industry would be only too happy to co-operate in creating such a ‘star’; and audiences would flock to Within the Law and any of the star’s subsequent films. Initially at least, it all went perfectly according to plan.

The competition was first announced in the Daily Sketch on 11 September 1922. A letter from Norma Talmadge announced that she was looking for a British film star:

Dear Sir – I have always said those who argue the British girls are not as good film actresses as American girls are wrong. I want to prove that I am right. Will you, with your splendid Daily Sketch, find for me a young girl in England, Ireland, or Scotland – a true, typical British girl, who would like to become a really great heroine of the films?

She was not looking for beauty necessarily, but for talent, an appetite for hard work and character. Hopeful unknowns (no established actresses were wanted) were to send in a photograph and a short description of themselves. Contestants were to apply to one of twenty-one districts nationwide; in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Newcastle, Blackpool, Manchester, Liverpool, York, Leeds, Nottingham, Birmingham, Cardiff, Bristol, Brighton, Norwich, Belfast, Dublin, and for London, Marble Arch, Whitechapel, Holloway, Lewisham and Clapham. Committees were to be set up for each centre, from which the one hundred finalists would be selected for the screen tests. The closing date was 22 October. Although the competition was planned on a grand scale, they must still have been overwhelmed by the response; 80,000 would-be British film stars entered.

Norma Talmadge’s Smilin’ Through was conveniently released at the same time, and for their side of the bargain the Americans certainly got a great deal with very little effort. The success of the promotion and competition owed everything to Hulton’s remarkable press campaign, which engrossed the whole country for two months. Every issue of the Daily Sketch featured photographs and details of the entrants, accounts of the deliberations of the regional committees (generally composed of the local mayor, mayoress and other dignitaries), and letters of advice from Norma Talmadge, detailing what she was looking for in her British film star, such as this:

A will to work, tireless energies, temperament, but a character that will prevent her from becoming spoiled by prosperity and success. Sufficient education to enable her to study and fathom the emotions of the characters she is called upon to portray. Ambition, but willingness to profit in the wisdom of others. Her eyes should be large and well shaped. Blue eyes are a detriment, but they may be ‘managed’ if all other features are good, and if the girl develops a strong personality. The nose should be straight. The lips should be well marked, but the mouth must not be too large. The lower part of the face must not be too heavy, or broad. Teeth are important – and must be regular and good. They show clearly, and in great detail, when the camera catches a smile. She should be under, rather than over, average weight; her ankles must be trim and her wrists neat. Her hands and feet not too large. She must have inherent grace of action – must know how or be capable of learning how, for example, to walk across the room properly in front of the camera. This may become a matter of teaching, but the girl without some inherent grace often finds it most difficult to learn.

Despite such an intimidating list of requirements, the photographs flooded in. With most of them the poses bore strong resemblance to stars of the day, Mary Pickford and Norma Talmadge herself being favoured in particular. The anxious wrote in to the Daily Sketch with fears about their noses, eye colour, glasses and ankles. Some, of course, appealed to Norma Talmadge directly:

Dear Miss Talmadge – I read of your splendid offer in the Daily Sketch, and writing to ask you to help me. I have always been ambitious to become a kinema actress. Please, will you help me? If only you knew how I pine for a career! Oh, please help me.

I am a typical English girl, and if I am chosen I will work hard to be a credit to England and you, and also strive to surprise America.

My parents have told me that I may go with you if you would take me. They would trust me in your care.

Oh, Miss Talmadge, if you only knew my hoping, wishing, and longing you would not pass me by, I am sure.

My age is sixteen, and ever since I was ten years old the screen has been my hope. I am praying day and night for you to choose me. I am aware that it is selfish of me to ask of you an especial favour, but I know you will forgive. But, please, help me. Please, do help me.

Only Heaven and myself know of the ambitious hope with which I send this letter and my photograph.

On 2 October 1922 Hulton’s newsreel Topical Budget announced its part in the ‘Daily Sketch film star competition’, and over the following weeks filmed contestants in Brighton, Blackpool, Bournemouth, Bristol, Glasgow, Leeds, London, Manchester, Newcastle and Sunderland. Under titles such as ‘Thousands of British girls want to be a film star’ and ‘Who will be the new British film star?’, items in the newsreel would, typically, show a group of contestants posed together in a woodland setting, then filmed in close-up individually, slowly turning their heads and smiling. The Daily Sketch ran articles and featured photographs on those entrants who were lucky enough to appear in the newsreel. Chaos ensued when the Pavilion Cinema in London’s Shaftesbury Avenue conducted its own competition to select one of the cleverly named shortlist, the ‘Lovely Hundred’. Traffic was held up by the crowds, and the Topical Budget cameraman could only film the entrants by climbing onto the roof of a taxi. Subsequently they were all able to see themselves portrayed on the Pavilion screen. Other cinemas featured photographs of local contestants in their lobbies.

The competition grew as time went on. A Grand Committee was announced which would help narrow the final hundred down to twenty; its members would include Lord Ashfield, Lady Diana Cooper, Sir Gerald Du Maurier, Lionel Tennyson, theatre manager Seymour Hicks and film distributor Sir William Jury. It was then announced that, as an additional prize, five contestants would be invited to appear in Diana Cooper’s new feature film The Virgin Queen (the celebrated society beauty experimented with a short film career at this time). It also transpired that at least two current British film actresses had entered their names, or someone had entered their name for them, as Edith Bishop claimed rather weakly had happened to her. They were disqualified.

Norma and Constance Talmadge arrived at Dover on 7 November. By now the ‘Lovely Hundred’ had been selected and the photographs of all of them printed in the Daily Sketch. As had happened when Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford came to Britain in 1920, and Charlie Chaplin in 1921, the country went wild at the sight of Hollywood glamour. The Talmadges were mobbed by crowds on their arrival in London. But although most of the country had greeted the idea of the contest and a real British film star with enthusiasm, there were some dissenting voices. The Film Renter viewed the whole affair with some amusement, and having described the Talmadge’s arrival at Dover – nothing that their entourage included such figures as ‘Susie, the mulatto maid’ and Esmeralda, Norma Talmadge’s pet tortoise – the paper denounced the whole stunt as a ‘cheap circus affair’ and expressed surprise at Hollywood stooping so low:

It is astonishing to think that First National should have lent their name to such a stupid piece of buffoonery. Surely the day is past when stars need such cheap methods of publicity, and it is not fair to the Talmadge sisters or to Mr Schenck that they should have been made the victims of circumstances which have certainly made these genuine screen stars look on one or two occasions a little ridiculous.

The circus rolled on. The Talmadges lunched with the hundred at the Savoy, after which they all went to the fifth ‘Victory Ball’, where Lady Hulton gave a speech. The following day the process of filming the screen tests began at Stoll Film Studios, for which First National had brought their own cameramen. Norma Talmadge, it was said, saw to the make-up of each contestant and was reportedly engrossed in her task. The first screenings took place on 10 November, with more filming in the afternoon, followed by final screenings the following day. The Talmadge sisters, Schenck, other representatives of First National, film director Edward José, and members of the Grand Committee all sat and watched the one hundred screen tests at a viewing theatre in Oxford Street and whittled down the entrants to twenty-one. After repeated screenings, they had three finalists. Finally, and after much agonised debate, they had one.

On Tuesday 14 November the Daily Sketch had a full front page photograph of the winner. She was Margaret Leahy, an Irish girl aged twenty, who worked in London for a Brixton milliner, and lived in the Marble Arch area. ‘A perfect film face’, said Norma Talmadge, adding that she had ‘splendid eyes, a supple body, and convincing expressiveness … her features are so perfect, and her character so distinctive!’ She had had the greatest difficulty in choosing from her final three, and had almost decided to take the other two, Jean Jay and Irene Coney, to Hollywood as well (Jean Jay was indeed to appear in a few British film productions in the mid-1920s and to write scenarios). But ‘Bubbles’ Leahy it was, whose face immediately appeared in newspaper advertisements for shampoo and toothbrushes. Topical Budget showed Norma Talmadge presenting her with a bouquet, and her appearance at the Marble Arch Pavilion at the premiere of Constance Talmadge’s East Is West, where she made a speech to the audience and was introduced to the Duke of York (the future King George VI).

The Daily Sketch printed her life story, such as it was, and the details of her prize. She would first spend a week touring all the major cities of the country, then sail to America, being paid £100 a week and chaperoned by her mother (also called Margaret), when after suitable training she would appear as Aggie Lynch, second lead in Norma Talmadge’s new feature film, Within the Law. She would then be given her own starring production. She would be under Norma Talmadge’s special guidance, but if she showed a special talent for comedy would be looked after by Constance Talmadge (Constance’s specialism was light comedy, Norma being more of an ‘emotional’ actress).

So far the competition had been an outstanding success. The Talmadges were the toast of the town, East is West was going to be a huge success, the Daily Sketch and Topical Budget triumphed in the publicity, and Margaret Leahy was proving to be a very popular winner. She went on a rapid tour of the country where she was greeted everywhere by large and enthusiastic crowds. Having said goodbye to the Talmadges at Southampton, her hectic national tour took in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, Cardiff, Bristol, Brighton and Southampton. She reportedly collapsed three times during the week. On 25 November, having been wished farewell by crowds in London, who sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’ to her, she left for Hollywood on the Aquitania.

Everyone was anxious to know how she got on. Postcards of her were put on sale, and the Daily Sketch commissioned her to dictate a diary of her experiences (a secretary accompanied her throughout). These touching and observant dispatches show something of the character which Norma Talmadge presumably had seen in her. America knew all about the competition and was just as excited by her imminent arrival. It was said she was to be given the Freedom of New York, and D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin sent her telegrams of congratulations. She arrived on 3 December and lights from skyscrapers flashed out a Morse code message of welcome. Amongst the huge crowd on the quayside to greet her were the Talmadges, Marion Davies, Anita Stewart and Katherine Macdonald, while Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish were said to have sent representatives to meet her.

The following day she met her director, Frank Lloyd, and went for her first tests at the studios in New York. She was made to walk through a garden setting and tested under different lighting conditions. D.W. Griffith was there, looking on in the company of Joseph Schenck. ‘I wonder what he thought of me’, she wrote. Griffith probably exchanged words of concern with Schenck, because they swiftly realised they had a problem on their hands. Margaret Leahy, however attractive, and despite the screen test in Britain, could not act. ‘She could not even be coached in the mechanics of walking, standing and sitting down’, says Rudi Blesh, Keaton’s biographer. They may have hoped that further coaching would cure matters, but already a rumour was allowed to circulate that Miss Leahy would be the star of Buster Keaton’s new comedy. This may have been the starring role to follow her second lead, promised as part of her prize, or else Joe Schenck was already preparing for an alternative strategy.

After seeing the sights of New York, Margaret Leahy and her mother travelled with the Talmadges and company by train to Los Angeles. Norma Talmadge appears to have been remarkably attentive to her throughout, partly no doubt because her reputation might depend on it, but also it seems out of genuine concern for her British protégé. Crowds bearing banners greeted her on her arrival in Los Angeles, and Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin came to meet her. Soon she was in the studio, with Frank Lloyd trying to turn her into an actress. Her diary ingenuously describes her doing a scene fifteen times. ‘They have taken thousands and thousands of feet of film of me’, she wrote, ‘Mr Lloyd says he is very proud of me’. Work was then halted until after Christmas.

As Blesh recounts, Frank Lloyd told Schenck that nothing could be done with her; either she went or he did. Clearly she could not be allowed to ruin the film or jeopardise the Talmadge name. Yet equally clearly there would be the likelihood of legal action if they sent her back without having appeared in anything at all, quite apart from the embarrassment that would occur following all the interest aroused on both sides of the Atlantic.

The solution was at hand. Buster Keaton was married to Natalie Talmadge. She was overshadowed by her famous sisters, being simply a secretary at First National. Keaton, having made a number of comedy shorts and appeared in one feature film, The Saphead (1920), was about to direct his own, The Three Ages. Dominated personally and professionally by the Talmadge clan, Keaton was in no position to object when Joe Schenck told him that Margaret Leahy would star opposite him in his new film, because ‘comic leading ladies don’t have to act’. It was also pointed out to him that British interest in Leahy would guarantee him success in that country. The part of Aggie Lynch in Within the Law went to American actress Eileen Percy.

In her first diary entry for 1923, Leahy told Britain the good news:

Thursday. Tonight, as I write, I am really crying. It seems unbelievable. My telephone bell rang this morning, and the maid said it was New York calling me. It was Mr. Schenck – the first time he has telephoned to me. He talked a moment about little things, and then he said, ‘Now, then, Miss Leahy, I am going to tell you something that will surprise you’. And then I learned that I am to be made a star right away. That they think they can trust me with the biggest prize of the year. To play the lead in the big Buster Keaton super-production that all the film fans in America are eagerly waiting for. It really doesn’t seem true – but it is. On the signs and in the printing it is to say, ‘Mr. Joseph Schenck presents – Margaret Leahy!’ Think of it! It is all due to Norma. The secret thing – she didn’t tell me a word. But she and Mr. Lloyd, it seems, have been so pleased with me and my film tests that they have decided it would not be necessary for me to play the second part in ‘Within the Law’ at all. That I can take a star’s part right away – with some training of course. Buster Keaton is the most popular comedian in America after Charlie Chaplin. He is to do a great super picture, which is to be one of the biggest productions of the year in America. Every actress in America has been begging for this opportunity – to star with Buster Keaton in this big new film. And Mr. Schenck, the producer, at last decided that I should be The one. ‘I am going to show England what we think of its Daily Sketch girl’, Mr. Schenck said. Of course, I cannot write any more now.

Reading between the lines of some of her dispatches, she was clearly afraid of rejection, and relieved not to have been sent home a failure. However, she was still being given the full star treatment by Hollywood, chatting to people she could previously only have dreamt about, and being interviewed by fan magazines. She was given the Freedom of San Francisco. People wrote to her requesting beauty tips. She was reported to have received two hundred proposals of marriage. This was also the time of the great scandal over the death of the drug-addicted Wallace Reid. Leahy mentions meeting Will Hays and the climate of worry that existed, and the several references to how well she was being chaperoned were clearly insisted upon to let Britain know that all was well.

Work began on The Three Ages. Her diary faithfully describes her efforts and failures, how she had to be taught to walk in a studied manner and not to move too quickly, how she ruined some scenes, and of Keaton’s patience with her. Her observations, though very much from the point-of-view of a star-struck cinema fan who had never considered how films were made before, offer some interesting details of Keaton’s working methods:

It is only preliminary work that we have done so far. Mr. Keaton is not quite sure yet about several points in the picture. It is to be a super comedy, and several of the scenes and incidents are tried out before they are actually taken – that is, we do certain scenes two or three ways before the camera, then we see them run off in the little projection room, and Mr. Keaton finds things wrong with them or gets better ideas, and then we do them over again. When these difficult points are cleared up we will start again, and work the picture right through. There is a scene in which there is a fire – a whole house seems to be burned down, and we have burned it down three times now, and still Mr. Keaton is not satisfied. Of course they do not really burn down an entire house. They build just the front of it. They build it at night, working all night, and then we burn it down in the day time. Mr. Keaton says if he can’t get the house to burn down properly he will cut it out of the picture after all.

Margaret Leahy appears from her photographs to have been a little less than ethereal figure, and certainly Norma Talmadge thought so, as Leahy reveals in this entertaining passage:

I have one very important thing to do. It is on my mind day and night. Norma told me in England I would have to take off ten pounds. She watched me all the time and broke me away from eating any sort of candy or sweets, and as soon as we came out here she made me start in earnest to ‘reduce’. Think of me ‘reducing’ – but I find there is hardly a star here who isn’t always ‘reducing’. We are all so afraid of becoming too heavy. ‘Ten pounds off, Margaret’ is what Norma even sings out to me when we pass each other in our cars. And ‘ten pounds off’ it must be if I starve to death.

In this section from her diaries, where she notes again Keaton’s habit of improvisation on set, she refers to a director, who is clearly Eddie Cline, Keaton’s credited co-director on the picture. We hear of two directors at work, one calling from beside the camera, the other the star on the set, changing gags and other business as he sees fit, while the cameras continue to roll:

Working with Buster Keaton one has to keep one’s wits. We rehearse a scene and then the director calls, ‘All ready. On the set (that is to say on the stage before the camera). Shoot!’ Then we start the scene just as we have rehearsed it. But Mr. Keaton may have a sudden idea right in the midst of the scene and will start doing something entirely different from what we had rehearsed. If I can ‘follow’ him, or understand instantly what he is doing and what I should do – then everything is all right. But if I am surprised the least bit and ‘caught napping’, then the scene is spoiled. The director shouts ‘Off’ and the camera stops and we start over again.

I went through one whole day splendidly. Mr. Keaton changed every scene right in the middle of it. For example, in one scene we had rehearsed for him to go slowly out of the door, hat in hand, and turn at the door to wave good-bye to me. I was to stand very straight and solemn – angry with him and indignant. Not noticing him at all as he left. Then, just as he pushed up his hat and started to go out of the door he changed his mind. He threw his hat down and came over to me and grabbed me in his arms and kissed me. I hadn’t the least idea he was going to do any such thing. I heard him coming up behind me, but didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t know what to do – what he had in mind. So I ‘took a chance’, as they say here, and just picked up a vase that was on the table and smashed it on the floor – to show how angry I was. The director shouted: ‘Good girl – hold it – hold it. Get out, Buster, quick – hold it, Margaret, till he’s gone – just that way – there you are – Off’.

I almost fainted with suppressed excitement when the director finished with that ‘Off’, which meant the camera stopped and I could sit down. ‘Whatever did you do that for?’ I asked Mr. Keaton. ‘Oh, just had a notion to change the ‘business’, he said, ‘and you got away with it splendidly’. But another day I hashed every scene we did because he changed so much and I could not catch on quick enough. But he expects this.

Her last diary entry was published in the Daily Sketch on 24 February 1923. Work proceeded on the film, with Keaton seeing any number of good scenes ruined and much re-shooting taking place, although he treated her with kindness and tolerance throughout. On 11 June she returned to Britain for the film’s premiere, the first major American feature to be premiered in Britain (it was not shown in the USA until September). Enthusiasm for the new British film star had not waned, and again large crowds greeted her on her arrival at Liverpool, though strangely the Topical Budget newsreel did not cover her return at all. She then went on to Paris, apparently to film some scenes for her next picture, before arriving in London at Victoria station on June 22nd. But she was worried about how her work would be received. She told journalists: ‘Please tell everyone ‘The Three Ages’ is my first picture. It is my beginning. I hope I shall improve in my pictures’.

Excitement was as high as when she first won the contest. She made a speech on the 2LO radio service, and then the charity premiere took place on her home ground, at Marble Arch, on 25 June. Princess Alice attended. Leahy, as courageous and honest as ever, gave a rather sad little speech before the show:

Your Royal Highness, my lords, ladies and gentlemen. I cannot say anything except to thank you from the bottom of my heart for coming tonight to see poor little me, for I am after all, just a Brixton shop girl. You will see to-night my first picture. I am very unhappy now as I look around me. I am very afraid you will think I have not been worthy of you. But I shall work very hard to be better and better as my career goes on, and then, someday, I hope you will greet me here and say I have done well. Then I shall never be unhappy again.

The audience cheered when she first appeared on the and warmly applauded the film. It was well made and funny, and as Joe Schenck had guessed, the film was a success, with many people in Britain going to see it purely on the strength of ‘that nice English girl who won the contest’. But Leahy was being honest with herself. She is not very good in the film, though thanks to Keaton’s hard work she is in no way bad. She is wooden, certainly, but makes some attempt at a performance, and looks attractive enough for Keaton’s character’s efforts to seem justified. Knowing all that she had been through to get there, the first shots of her, seated alone on a rock in Stone Age dress, looking slightly apprehensive but prepared to do her best, have for us now a special poignancy.

The Three Ages was Margaret Leahy’s first and last film. There do appear to have been attempts to find her another vehicle (with all that publicity it would have been a waste not to), with rumours of a British-French co-production and the filming in Paris. She was made one the Wampas Baby Stars for 1923, the annual list of thirteen potential female film stars chosen by Hollywood publicity and advertising executives. Eleanor Boardman, Evelyn Brent and Laura La Plante were future stars chosen that year alongside her.

But such plans came to nothing, and it appears that Leahy herself decided against a film career. After a short tour promoting the film, she returned to America, declaring that it was nice to see England again but she missed the California skies. What acting qualities Norma Talmadge first saw in her it is hard to determine. But what is incredible is the enthusiasm aroused in Britain for this ready made film star. What a sad picture it all makes of the national inferiority complex and the dream of Hollywood. Did they really believe that she would be turned into a film star, with a series of films devised to suit her talents? Even the Americans seem to have been taken in by their own magic for a while.

Cinderella did not return to her rags, she went back to California, eventually married and settled down. We know little of her subsequent life, except (as Marion Meade recounts) that she became an interior decorator at Bullock’s department store, and that sadly she came to loathe the movie business and burnt all her scrapbooks, before apparently taking her own life in Los Angeles on 17 February 1967. But something does remain – the newsreels, the newspaper diary, The Three Ages itself, and the touching, revealing story of how a Brixton shop girl did manage, for a brief while, to achieve the dream that eluded millions like her, and win her way to stardom.

Note

This post is based on the records of the Topical Film Company (producers of Topical Budget), held by the British Film Institute; the film trade papers The Bioscope, Kinematograph Weekly and Film Renter; the Daily Sketch newspaper; Rudi Blesh, Keaton (London: Secker & Warburg, 1967) and Marion Meade’s Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase (New York: HarperCollins, 1995). Since this was first written for the busterkeaton.org site in 2000 a collection of photographs from Leahy’s time in America in the early 1920s and an album of newspaper cuttings made by a relative of hers have come to light. These are now held by Learning on Screen in London (https://learningonscreen.ac.uk), to whom thanks are due for permission to reproduce some of the above photographs. The essay was rewritten for The Keaton Chronicle, vol. 19 issue 3, Summer 2011, but disappeared from busterkeaton.org after a site redesign in 2018. I have therefore reproduced the 2000 text here, with a revised selection of images. It is too good a story to be lost.

A poignant story indeed, with many resonances. Well worth rescuing and putting forth again. Thanks Luke!

Thank you Ian. An old story, which I first came across thirty years ago. I could find out so much more were I to research it all over again, but I rather like it as it is. The resonances have only grown over the years.