At the start of the current exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt, you are told that 25% of the people on the planet play video games. I am one of the 75%. I do not play video games; indeed, I do not think I have played a video game of any kind since Pong, in the mid-1970s. I have seen many a game being played by others, and briefly I have pushed the same buttons or waved the same joystick to see what the technology did, but only out of passing curiosity. There was no appeal, nor much understanding on my part as to what that appeal might be. So what was I, as a representative of the excluded 75%, to get out of an exhibition on video games?

Well, the simple answer is quite a lot. It’s an excellent exhibition: in its presentation, layout, understanding of its subject and appreciation of its audience. It makes particularly good use of space, with no wasted corners, and a keen sense of the dramatic – midway through the exhibition there is a grand coup de théâtre when you walk into a hall-like space with a huge display screen towering above you, the audience clinging to the edges of the room for the finest view. There is a startling use of a long screen showing up to five life-size interviewees against a background. Four are frozen at any one point, while one speaks (with subtitles). The debates were compelling, the viewers transfixed. There was so much active technology on display – invariably a nightmare for exhibition organisers, yet everything was working.

The exhibition’s theme is the design and culture of the contemporary videogame. So it’s not a history of the video game, and many of the most celebrated titles – i.e. the ones that even I have heard of – are absent: Halo, Grand Theft Auto, World of Warcraft, Tomb Raider. Instead it presents examples of cutting edge design and critical ideas, showing how the creative minds behind the phenomenon are continually challenging what they do. The more they establish themselves, the more they wish to break free, particularly beyond the confines of story. That was the exhibition’s primary theme for me: the compulsion towards yet the equal reaction against conformity, especially narrative conformity.

It helps to be accompanied by someone acquainted with this world, and I was fortunate in having a 16-year-old with me who knew not only every game but had a strong interest in design as well. It’s a world that excites the intelligence, if the intelligence is there to be excited.

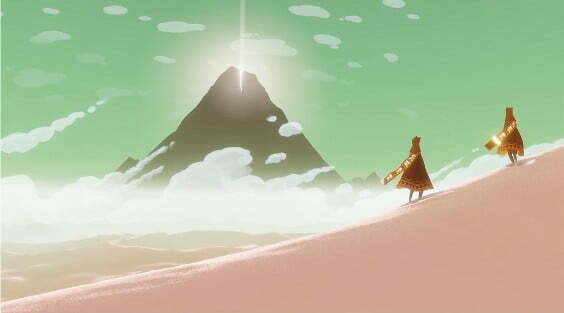

Not knowing my way around this landscape, I looked for reference points outside it. The dreamy landscapes of Journey, designed as an exploration of an endless landscape beyond the narrow confines of narrative, reminded me strongly of the space fantasy album covers designed by Roger Dean, de rigueur for any 1970s prog rock band. The storyboards looked comfortingly like those of a film, while the creators of the assorted games often identified films as reference points (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, Death of a Salesman, somewhat surprisingly).

Film comparisons seem the most pertinent. It’s not just the much-cherish cinematic qualities (to be called ‘cinematic’ in this world is a badge of honour). Video games share with film a universality that truly transcends borders. Film was the medium that succeeded everywhere, with the same product. There was, and remains, a particularity to that product, because it was American film that became pervasive, not films of any kind from any territory appealing to any audience. So it was, and remains, culturally idealist and culturally imperialist at the same time. Video games likewise are played by everyone (or 25% of us) and most of those playing are playing the same games, often with others across the world at the same time. And likewise there is domination of American companies and culture to some degree, but also of the English language. There’s a compelling section in the exhibition where we learn that you cannot code powerful games in Arabic. English is the very lifeblood of the video games industry.

It is an interesting exercise, trying to understand other people’s stories. Much of the problem I have had with video games is that the narratives seem so unsatisfying. Everything appears to be a quest or a shoot-em-up. It is relentlessly linear, wearingly narrow. Characterisation never rises above the crudely simple. Atmosphere is everything, human interaction is minimal. There is nothing to be learned from such stories. They are just games.

But of course such an argument ignores the major component of the narrative, which is the gamer. It is we who make the story. Traditionally stories present us with a credible world in which an adventure takes place and a lesson is learned. We may identify with one or more of the characters involved, but fundamentally we are witnesses. We encounter impossible worlds in which everything comes together and make sense (which is why they are impossible), for our entertainment and instruction. In video games we inhabit impossible worlds which only make sense because we are moving through them. It’s not really a shift from the passive to the active. Rather, it is a shift from the illusion of community (everyone shares in these stories, most visibly in a cinema) to the illusion of individuality. We move through worlds of our own choosing.

That must mean, ultimately, a fundamental shift in how stories operate for us. We escape into these worlds, but they are worlds from which there is no escape. We are constantly on guard, not simply because that monster is lurking around the corner, or because that sinister figure heading towards us is carrying a weapon, but because if we are not there then there is no story. It is pure solipsism. Without us, the world ceases to exist. Who can say what a psychic burden that may place on us in the long run?

I admired the skill and creativity on display at the V&A. I saw something of the video game’s appeal. But I think I am happier staying with the 75%.

Was there any mention of modern board games being presented as computer games? It’s a growing trend. It’s probably easier than taking all the cardboard pieces out of the box to setup the “real thing”. Some of my people like to practise their board games at home, online, but I think it misses the face-to-face/tactile touch.

Hi Nathan,

Not that I recall. That sounds like an interesting trend, but the exhibition does not attempt to cover all types of video game or the breadth of its history, instead focussing on questions of design (which is the V&A’s brief as a museum).

I do of course play chess online, or against machines. But chess is always different.

I’m another in the non-gaming fraternity. Very interesting article.

I feel after writing this that I ought to try one video game at least, to make my pronouncements a little more practical and not so utterly theoretical. I shall report back.

Many years ago I enjoyed text-based adventure games like Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It followed the events of the first book pretty closely. I was inspired to design a game based on Hamlet, but I didn’t past the scene with the ghost on the parapet. Infocom’s text-based games were the first programs I saw that were really good at parsing natural language.

The Hamlet game is one that I would have played!

I look forward to reading what you make of it.