Currently running at the Bruce Castle Museum in Haringey, north London, from April to July 2019, is a small exhibition on local film pioneer Robert Paul (1869-1943). Entitled Animatograph! How cinema was born in Haringey it traces the one small corner of the achievements of a man who, looking back on his life might have viewed in terms of achievement over a number of decades in the field of electrical engineering, but who is now chiefly remembered for a side activity that look up a dozen years of his life.

Paul was one of the people who launched the film business in this country. To be accurate, he was one of the two people who did, though he was the better businessman. He collaborated with a photographer who could help him make films, Birt Acres (they were brought together by a third party, Henry Short). Paul had discovered the new medium when two Greek businessmen, Demetrius Anastas Georgiades and George John Tragidis, approached him late in 1894 with a proposal to make copies of the Kinetoscope, a peepshow device for showing film which Thomas Edison had invented but had neglected to patent in Britain. Paul built the machines, then turned to film production to supply these machines for his own business benefit, working with Acres until the two fell out mid-1895. Each went on to achieve projected film with their respective machines early in 1896 (Paul’s was called the Animatograph). Acres soon slipped into obscurity, but Paul went on to become one of the leading lights of the early British industry until he quit the business in 1910.

it’s a story much romanticised in some quarters. To the outsider it is a somewhat mundane tale of business development – a new product, some early shenanigans, improved technology, some money made. Were it the tale of any one of the other electrical devices with which Paul was associated, such as the Unipivot galvanometer, then who would care bar a few historians of technology? But Paul’s machines made movies, and so became the engine of dreams.

The exhibition strikes an appropriate balance between the mundane and the magical. It mostly comprises illustrated panels on the stages of Paul’s film career, with some posters, objects and video projections. It transmits some of the thrill those who are dedicated to this period cannot fail to feel each time the story is told. It captures the peculiar pleasure one gets from seeing the roots of lofty cinema found among the unprepossessing streets of somewhere like Muswell Hill. The exhibition has been put together by Professor Ian Christie of Birkbeck, University of London, tireless film historian and film proselytiser, whose long-awaited book on Paul is to be published by Chicago University Press in November 2019.

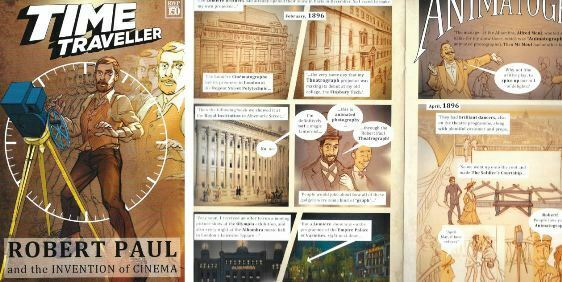

The highlight of the exhibition when I visited was a slim graphic novel, produced by Christie and comic artist ILYA, which tells the story in excited comic strip form. It is entitled Time Traveller: Robert Paul and the Invention of Cinema, the title coming from H.G. Wells, whose story The Time Machine inspired Paul to submit a patent application in 1895 in which the spectator would be transported through time and space by viewing films. Paul’s application has some practical ideas (it anticipates the Hale’s Tours of ten years later in which film was projected at the front of a mock-up, rocking rail carriage to give audiences a sense of virtual travel), but is chiefly interesting for its visionary flights of fancy:

After the starting of the mechanism, and a suitable period having elapsed, representing, say, a certain number of centuries, during which the platform may be in darkness, or in alternations of darkness and dim light, the mechanism may be slowed and a pause made at a given epoch, on which the scene upon the screen will come gradually into view of the spectators, increasing in size and distinctness from a small vista, until the figures, etc., may appear lifelike if desired.

The booklet, which pleasingly combines comic art with film stills, turns ordinary business into romance, north London small businessmen into heroes. All early film histories ought to look like this, was my reaction. It understands the thrill of a startled Victorian age stumbling across the modern.

But though we can dream of them as visionaries, they were very ordinary in reality. Several of the British film pioneers have been the subject of biographies recently, or have biographical studies in the works: Robert Paul, Charles Urban, Cecil Hepworth, Maurice Elvey, George Albert Smith, James Williamson, Arthur Cheetham, Wordsworth Donisthorpe. Few were remarkable, except that they were firsts. Donisthorpe was a political visionary, Urban a salesman of uncommon gifts, but most of them, and most of their peers, were ordinary folk, albeit with extraordinary dreams.

The Wells story that is most appropriate for such humble visionaries is not The Time Machine but The History of Mr Polly. Polly, the lower middle-class draper’s assistant who pursues uncertain dreams, is certain only in his need to escape from where he has found himself. The early British film business was populated by Mr Pollys, who sensed that they had stumbled upon the path to something remarkable, but never really got beyond moving from one shop to another, while those elsewhere (chiefly in America) thought in terms of giant stores and franchises. Wells, who knew something of film (it seems that he met Paul in 1895), might have made something interesting of such dreams, frustrated no doubt by the stubborn annoyances of misbehaving technology and mercurial audiences – there was a rather charming ATV series made in 1980, Flickers, with Bob Hoskins as an early film exhibitor with social pretensions, which captures something of the Wellsian spirit. But when Wells finally wrote a cinema novel, The King Who Was a King, in 1929, it was singularly lacking in charm or understanding of the medium. I do not recommend it to you.

Paul, and his fellow film pioneers, all have their stories that are well worth telling. Few would be the worthy subject of a biography if they did not have that pioneer status to their name, but it is there, and as the film medium continues to change (Time Traveller starts with children looking at their phones when H.G. Wells steps out of the past to greet them) we revisit its roots and see new analogies, new evidence, and new ways of looking at old evidence. Paul will always be reinventing his invention.

Nevertheless, the Mr Polly label remains. In another part of Bruce Castle Museum (a rambling, pleasing, former 16th century manor house) there is a room with an exhibition about another group of inter-connected people. Its subject is black Georgians – some of the notable black British citizens of the eighteenth century whose names came to prominence at the time when protests were growing against the slave industry. The names are starting to become familiar – Olaudah Equiano, Ignatius Sancho, Phillis Wheatley (an American poet who visited and was published in Britain), Dido Belle, and most surprisingly James Townsend, eighteenth century resident at Bruce Castle and a Lord Mayor of London, who – probably unknown to him – had black ancestry, his grandmother being the daughter of an African woman and a white soldier in the Dutch West India Company. The exhibition is little more than some small portraits and panels on their lives, but they have the thrill of true romance. In each life we see the fight for human dignity and a society in which all must belong equally. We see a British history re-invented into something more honest.

Most led greatly constrained lives, by necessity, but what lives nonetheless. In just a few lines of description we see character, determination, belief, people entrapped by their times yet forcing their way out to a new understanding. They speak to our age, true time travellers all. We must have film history, and there is much about the British pioneers that is engrossing and valuable. But it does not compare.

Links:

- There is information on both exhibitions at the Bruce Castle Museum section of the Haringey Council website

- There is more information on Robert Paul at Ian Christie’s Paul’s Animatograph Works website, with an illuminating post on the influence that Paul may have had on Wells

- I wrote about Ignatius Sancho and other black Britons of his time in an earlier post on this site

Well of course I’m more than somewhat biased, in several ways, but what a pleasure to read an informed, judicious review of one’s efforts to promote interest in Robert Paul. Luke’s playing down of the drama is a not unreasonable corrective to my enthusiasm for the era and its characters. Except, i would draw tge reader’s – and hopefully visitor’s – attention to two salient points not noted by Luke.

The first is Paul’s extraordinary prescription for ‘riveting’ cinema, published as a trade ad in October 1898 – which he apparently delivered, even if almost all the films are lost. And the second is Wells’ own realisation of cinema’s like future importance in the now little read When the Sleeper Wakes (initially 1898, but which he kept revising), where screen images latge and small get their due.

Did that awareness come from meeting Paul in late ’95, after The Time Machine had appeared? We’ll never know, but it remains a fascinating field of speculation…

Ian,

I’ll look again at that 1898 trade ad (I definitely want to visit the exhibition again). I refer to your investigations into ‘When the Sleeper Wakes’ in the links to the post.

Congratulations on a great show which is going to delight and interest people.

Luke

It sounds like a wonderful exhibit and I liked your comment about the book: “All early film histories ought to look like this.” I agree. I can think of several people who stories would make good graphic novels. I’m also happy you mentioned Flickers. I saw it on US television and found that it matched up well with the memoirs I had read about early movies.