It was back in 1992, when an envelope turned up on my desk at the BFI. It came from the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now EYE Filmmuseum), and contained a number of frame stills of very early films that they were preserving. They wanted help in identifying them.

They were marvellous, intriguing, baffling images. There were scenes from stage productions, travel shots from around the world, ships, trains journeying through spectacular landscapes, advertisements, unknown people smiling at you, waiting for the camera to start turning so they could start their act, war scenes (the Anglo-Boer War), royalty and once-celebrated celebrities. The images were remarkably sharp in detail. It was a lost world; it was a familiar world – and next to none of it was to be found in the film histories that were then available to us.

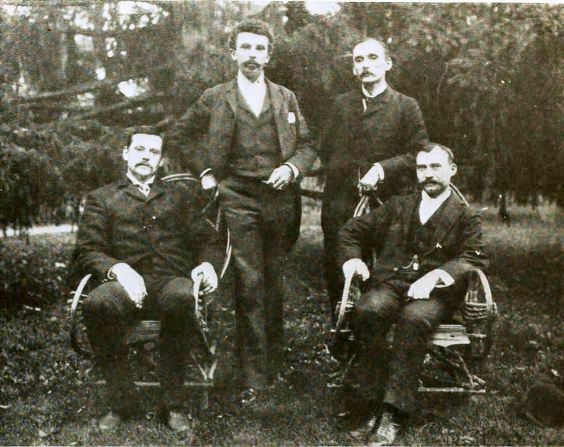

So began a remarkable adventure, uncovering a virtually lost part of early film history, whose rediscovery helped rewrote that history. The films dated from 1897 to 1903 and were made by members of the Mutoscope and Biograph Syndicate, a set of interconnected, international film companies which made film in 68mm format (some said 70mm, though strictly speaking it was 2¾ inches), four times the frame size of the standard 35mm that the cinema adopted after its introduction by Thomas Edison in 1893. Biograph was a name familiar to anyone who knew their film history, because it was the company for whom D.W. Griffith worked 1908-1914. It was known also that that company came out of the American Mutoscope Company, founded by the quartet of W.K-L. Dickson (British former employee of Edison), Herman Casler, Harry Marvin and Elias Koopman in 1895. The company was formed originally to exploit the Mutoscope peepshow device, which converted film into flick-cards, but it soon moved into film projection. The films were made in 68mm, but few had seen these films in anything other than 16mm reductions from indistinct paper print copies. What almost no one knew about at this time was the European side of the Mutoscope and Biograph business, and that is what we had to uncover.

The Dutch films had been discovered in cellar in 1948, collected originally by Dutch film pioneer Willy Mullens. They found their way to the Nederlands Filmmuseum in the 1960s, to be rediscovered in 1990 when the archive undertook an inventory of its holdings. At around the same time, the BFI’s National Film and Television Archive started looking at its own 68mm Biograph collection, which had been donated in 1969 by Dr Rolf Schultze of the Kodak Museum. Some attempts at copying these problematic films onto 35mm, with limited success (Biograph prints have no perforations, presenting a challenge to traditional film copying technologies). In the early 1990s the two archives worked together on copying the films onto 35mm, frame by frame, using devices specially constructed for the purpose. At the same time, a collection of American Biograph films on actual 68mm were revealed to be held by the Museum of Modern Art.

Even if we knew a little of the history, we knew next to nothing about the films themselves. So we started looking at them. As the 35mm reductions were produced by the NFTVA’s labs, each prosaically named ‘Schultze’ followed by a number, we screened them in our viewing theatre before a small audience of early film historians. What a thrill that was – I vividly remember what I think was the first of them, a shot of pelicans at London Zoo (Pelicans at the Zoo, 1898), which was startling in its clarity and high contrast. The films looked wonderful, but moved with peculiar slowness at usual silent film speed (Biograph films were filmed at anywhere between 30 and 40 frames per second, we discovered). Gradually we started to identify places, events and faces, and to match these to listings of the films found in newspapers, journals and to programmes in the archives of the Palace Theatre, showcase venue for Biograph films from 1897 to 1902, where it was regularly billed as being the ‘American Biograph’. We were greatly assisted in particular by Graeme Cruikshank, the Palace Theatre archivist, and theatre historian Barry Anthony, who went on to write a definitive history of British Biograph, with Richard Brown, entitled A Victorian Film Enterprise.

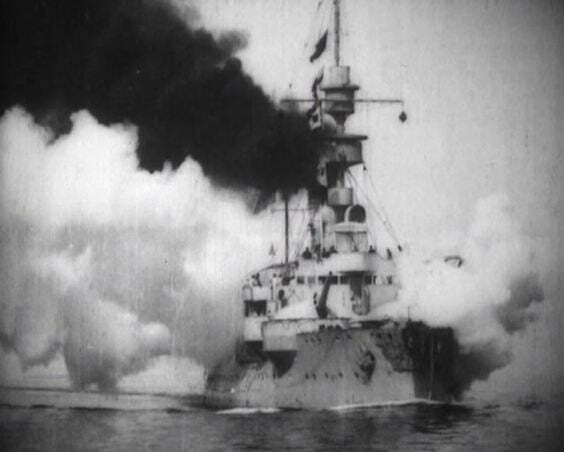

Complementary work went on in the Netherlands, and so around 300 films (200 at the NFM, 100 at the BFI) hitherto unknown were mostly named and dated: Afternoon Tea in the Gardens of Clarence House (1897), Antarctic Expedition – Sir Georges Newnes’ Farewell to Officers and Crew (1898), Duel to the Death (1898), Her Majesty the Queen Arriving at South Kensington on the Occasion of the Foundation of the Victoria and Albert Museum (1899), Battleship ‘Odin’ with All Her Guns in Action (1900), Battle of Spion Kop (1900), Lord Kitchener’s Arrival at Southampton (1902), Captain Deasy’s Daring Drive (1903). A whole world of the late Victorian era’s fascination with itself and where it was going unfolded before our eyes.

We started to screen them to the public. Selections were shown in 1995 at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna and the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy. At the start of 1996, I organised a series of Victorian film shows at the National Film Theatre, where we showed every film that we could get our hands on made around the world before 1901, include an entire show devoted to Biograph films. In 2000, the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone showed all of the European Biograph films then known and produced a special edition of its Griffithiana journal devoted entirely to Biograph, edited by myself and Mark van den Tempel, with essays from Paul Spehr (on his way to writing the biography of Biograph’s presiding filming genius, W.K-L. Dickson), Stephen Bottomore and Deac Rossell, amongst others.

King John (1899) – shown at far too slow a speed…

One of the British Biograph films reached a very wide audience indeed. Among the most exciting discoveries in the Dutch collection was King John, made in 1899 and the first ever Shakespeare film. Its discovery rewrote that corner of Shakespearean film history, culminating in part of the single-shot film featuring in a Shakespearean montage for the 1997 Academy Awards broadcast, viewed by hundreds of millions around the world. And it all began (for me) with a bunch of unidentified stills in an envelope.

But one thing was missing. Biograph films were made on 68mm film, but we were showing them as 35mm reductions, for sheer convenience. To get the real Biograph effect, the sheer astonishment experienced at the time of these larger-than-life images with that startling clarity, they needed to be shown as they were originally shown. More particularly, we knew that Biograph films were practically the same shape as IMAX, specifically IMAX turned on its side. The BFI was building an IMAX cinema at Waterloo, which opened in 1999. What a golden opportunity to show these films as they should be. If only someone could find the money…

It has taken a while, but nineteen years later Biograph has at last come home. Last night, at the London Film Festival, the BFI IMAX presented The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show, a programme of British Biograph films (together with other large format, 60mm films of the period made by Prestwich and Gaumont). They were digital restorations and not on IMAX film, but they were big – far bigger than they had ever been seen before (no Victorian theatre had a screen the size of the London IMAX). And they were astonishing.

The show was hosted by the BFI’s silent film curator, Bryony Dixon, who contextualised the films beforehand within a history of London performance and panoramic entertainments, before speaking throughout the films themselves in the manner of the film lecturers of old (many early film shows had someone explain to the audience what it was they were seeing). A lively band led by pianist John Sweeney provided the music. The films were broken up into themes, covering Victorian life, royalty and celebrities, military, the Anglo-Boer War, advertisements, comic sketches, theatre, train rides and so on. The films (there were 51 of them) found their natural space across the vast IMAX screen, inviting the viewer to examine every bit of enticing details, from the ostensible foreground subjects to the tiny bits of detail in the background – the passers-by and onlookers, unknowingly if marginally made immortal. The highlight, for me, was the concluding set of films of panoramic views taken from or showing moving trains. The world swirled round us with each curve of the track and the shifting landscape. We became immersed in the image, thrilled – just as the original audiences were thrilled – by the vicarious experience of motion.

One ends up agreeing with this hyperbolic review of a showing of the ‘American Biograph’ at the Palace Theatre in 1898, given in Punch (6 August 1898):

Then comes “The American Biograph.” Wonderful!! But, my eyes! my head!! and the whizzing and the whirling and twittering of nerves, and blinkings and winkings that it causes in not a few among the spectators, who could not be content with half the show, or even a third of it. It is a night-mare! There’s a rattling, and a shattering, and there are sparks, and there are showers of quivering snow-flakes always falling, and amidst these appear children fighting in bed, a house on fire, with inmates saved by the arrival of fire engines, which, at some interval, are followed by warships pitching about at sea, sailors running up riggings and disappearing into space, train at full speed coming directly at you, and never getting there, but jumping out of the picture into outer darkness where the audience is, and the, the train having vanished, all the country round takes it into its head to follow as hard as ever it can, rocks, mountains, trees, towns, gateways, castles, rivers, landscapes, bridges, platforms, telegraph-poles, all whirling and squirling and racing against one another, as if to see which will get to the audience first, and then, suddenly … all disappear into space!! Phew! We breathe again!! But, O heads! O brandies and sodas! O Whiskies and waters! Restoratives, quick! It is wonderful, most wonderful!

There is so much about Biograph that is instructive and engrossing. The history – particularly the economics of it – tells us so much about the aspirations that we held for moving images in their infancy and how they were viewed as a business. The technology employed fascinates the specialist. The European nature of the network of companies (UK, Netherlands, Italy, Germany, France, Belgium and more) shows how the film industry thought beyond borders while protecting its interests. The stories of the individual films and film series are rich in themselves – King John, the Alfred Dreyfus trial (filmed by the French Biograph company), the Anglo-Boer War films, the series made by Dickson of Pope Leo XIII (the BFI showed a film of the pontiff blessing the camera and by extension the audience of 1899 and ourselves today). Biograph shows how film was profoundly connected to the world that gave birth to it.

Most instructive is the experience of seeing the films on the big screen. They are not just big films, in every sense, but re-connect our jaded eyes with those of the original audience. The size and the detail encourage us to look deeply into the films, to read the action closely, to detect mini-narratives within the frame. We know that audiences of the time, for all kinds of early films, were that much more arrested than we tend to be now with small points of detail. They were wholly absorbed in foreground and background, attentive to every movement, spotting gestures, clothing, weather effects, interactions, people just being themselves, as they marvelled in the miracle of photographs that moved. They got so much out of what they saw. Biograph made big again makes us do the same. We look with new eyes, with old eyes.

Links:

- ‘How the Victorians first saw their world on film‘: BFI silent film curator Bryony Dixon writes about Biograph and other early large format films and their restoration

- I wrote about the Biograph films of Alfred Dreyfus and about Dickson’s films of the Anglo-Boer War on my Bioscope site

- Biographies of Dickson, Koopman, Casler, Marvin, Newnes and other associated with Biograph can be found on Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema

Update (April 1925)

The three hundred 68mm Biograph films held by the BFI, Eye Filmmuseum, MOMA and CNC have been added to the international UNESCO Memory of the World Register https://www.bfi.org.uk/news/bfi-68mm-films-added-unesco-international-memory-world-register.