Below is the text of a paper I gave recently at ‘Language Matters‘, the 5th Transfopress Encounter in Paris. Transfopress is an international network of archivists, librarians and scholars interested in the study of foreign language press. The subject of this conference was printed news in English abroad and foreign-language publishing in the English-speaking world. My talk, entitled ‘Newspaper data and news identity’ has been published on the British Library’s Newsroom blog, but I’m reproducing it here as well.

The British Library holds one of the world’s largest newspaper collections. It has some 60 million issues dating from the 1620s to the present day. The collection is fairly comprehensive from 1840, certainly so from 1869 when legal deposit was instituted, and publishers of British and Irish newspapers were required to send one copy of each issue to the Library. Issues from 1,400 current titles are added each week, along with a web news collection that archives over 2,000 news sites on a frequent basis, and a growing television and radio news collection.

Around two-thirds of the newspaper collection is British or Irish titles. Most overseas newspapers are now taken on only in electronic form or on microfilm, but we nevertheless have substantial holdings of overseas newspapers in English and other languages. This includes an extensive collection of newspapers from Commonwealth countries which were formerly received through colonial copyright deposit.

Our goal is to move from being a newspaper library to being a news library, reflecting the great changes taking place in the world of news today. In doing so we have had to ask questions about what the nature of news is. The definition we use is that news is information of current interest for a specific audience. Such a definition can be applied across different news media and suggests ways of linking them up, but also challenges the idea of what news is, since it can be applied more widely that that just those media we commonly identify as ‘news’. Anything can be thought of as contributing to ‘news’ if it helps inform our world. In particular, it draws attention to communities seeking out news that is meaningful to them, and asks how we should be expressing such audience identification in our catalogue.

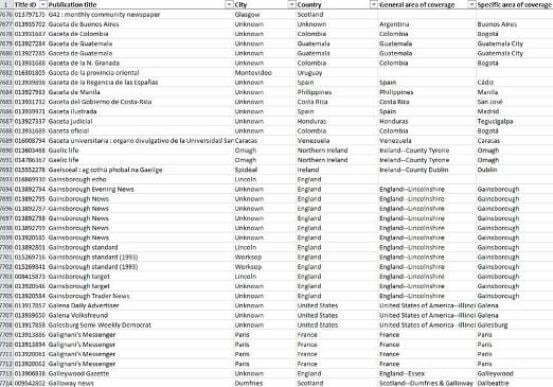

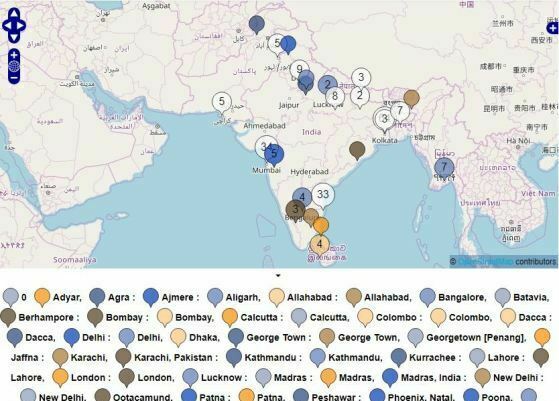

These issues have come to the fore in a project we have been undertaking, to produce a single title-level listing of all newspapers at the British Library (around 34,000 titles). Producing such a listing from a catalogue built up over many decades and from diverse collections has been challenging. It ought to be a simple case for a national library to produce a single listing of the newspapers that it holds, but in practice a significant number of newspapers have been classified as journals, or even books, on our system. Ensuring that we identify every newspaper as a newspaper has involved some prolonged research, in particular working with areas of the Library that cover particular geographical areas or communities.

For example, over the past year the News section in which I work has been working with our Asian & African department to identify Indian newspapers in the collection. Many of these had been classified as Journals on our catalogue, making discovery difficult for anyone looking for Indian newspapers without a specific title in mind. Multiple standards had been applied to the cataloguing of newspapers in the past, and there were additional problem particular to newspapers, such as changes of title and similarity of titles to other newspaper series. Previous investigations had indicated that we held some 214 Indian newspaper titles; in the end, 234 were identified by a research fellow, Junaid ul-Hassan. Each title was reclassified on our catalogue, the result being that what had previously been a buried newspaper collection has been opened up for researchers.

The Indian newspaper records each come with geographical codings, meaning that we can produce a map of their distribution, while research by Junaid into contemporary reference sources has given us a greater picture of what was published overall, from which we may judge how selective and representative our collection of Indian newspapers might be.

A significant number of our newspaper records still require better or more consistent geographical identifiers before we can say with confidence how many newspapers we have from different countries or parts of those countries, or before we can produce further maps such as we have for Indian newspapers. But what about diaspora newspapers? We have many newspapers past and present that have been published for and by different immigrant or ethnic communities within the UK. How does our catalogue reflect the existence of newspapers published by the different communities within the United Kingdom, be they identified by race, religion or particular political persuasion?

The short answer is that we cannot. There is no means of extracting information for the British Library catalogue that will identify all news published for immigrant or ethnic communities, whether in English or other languages. Our catalogue does not work that way. The newspaper titles are there, but but they are not classified in a form that would help us locate them. It is possible to identify some newspapers published in the United Kingdom by the language in which they were printed, which is one way of narrowing down diaspora newspapers, but it is an incomplete solution, since many will have been published in English.

The British Library catalogue primarily identifies a newspaper by its title, date range, place of publication and its geographical coverage. Traditionally, this has been enough. It is not the function of a research library to do the researcher’s work for them. We provide the basic list, comprehensively compiled and accurately described, and you must do the rest. You must know what it is that you are looking for.

But one can argue that such an ordering of the data is a form of suppressing identity. The catalogue becomes a political tool, creating conformity of identity through rules of description. Such an ordering reinforces the suppression of difference.

The function of the catalogue as something that replicates society’s power structures is well known. Catalogues and classification systems are never the value-free orderings of information that they advertise themselves as being, but are instead profoundly imbued with the values of the dominant society that maintains them.

There is an argument, therefore, that the newspaper catalogue could be doing more to identify different forms of newspaper by their audience and purpose, to counteract this impulse towards conformity.

Should this be a component of news cataloguing, and if so how should it be implemented, both for future news publications and retrospectively? How do we identify a news community, and how do we determine what their understanding of the news was, and from what sources they gained the fullest picture of the world in which they found themselves? As said, the definition of news we are employing is that news is information of current interest for a specific audience. This suggests that identification of audience should be playing a far greater part in how we catalogue newspapers than is currently the case. Cataloguing by nation and geographical area presupposes that all news is geographically determined, but this is not so. Those specific audiences may be determined by gender, age, special interest, belief, language or ethnicity. A community-led understanding of the news may be the necessary way forward – both in how we manage news collections today, and how we revisit the discoverability of our historical news archives.

One of the major growth areas for news in the UK is hyperlocal news. Hundreds of news websites, and in some cases newspapers, have been published independently on an amateur or semi-professional basis, that are aimed at small communities across the UK. Most of these hyperlocals are geographically based, as their name suggests, but they indicate the ways in which traditional structures for the production, ownership and identity of news are changing. they suggest that news is something that comes from us, however we choose to identify ourselves, rather than something that is decided for us. This is the logic of social media, where each of us selects the news world that is meaningful to them.

Another imperative is the direction in which digital libraries are going. As with some other national libraries, the British Library is now archiving its national portion of the Web, including newspaper websites and other news sites. The figures involved are overwhelming, with the number of pages being archived each now to be counted in the billions. Indeed, the amounts of published content coming in across all formats is growing at a rate beyond the comprehension of the ordinary researcher. When we curators at the Library give talks to people about what we are collecting you can see their eyes glaze over. There is too much to take in.

In such a world, there is a paradox. The more we acquire the harder it is to find the resource to make discovery through our catalogues practical, yet the greater the imperative must be to enhance discovery for those who do not need to discover everything, just something.

As collections grow exponentially, so does the need to contextualise them also grow. This cannot be managed by humans, at the rate things are going. It will need to come from algorithms, automated topic extraction, mapping tools and other forms of artificial intelligence. The future of cataloguing is automation, and in such a world it will be our job, as curators, to ensure that the machines address the right needs.

Those of us who manage news archives must rethink how we are managing them. When discoverability becomes overwhelming, and when traditional cataloguing structures hide records that do not conform, such as diaspora newspapers, then we must question what we are doing – and make changes. There will always be the single list of every title that we hold, because ultimately an archive is a collection of discrete objects, each identifiable by a title and a date. But we must think for whom the news has been shaped and published. We must produce discovery tools that bring to the fore different parts of the collection – a multi-faceted approach to replace the linear. We must be mindful of the identity of the news that we archive, without which it is not going to be news at all.