There are exciting changes happening in how we use newspapers to study the past. After decades in which the use of newspapers in research meant leafing through volumes or scrolling through microfilms, digitisation made millions of newspapers more readily searchable and far more widely available. But now that digitisation that taken us to the next stage in development, which is using the data generated by the digitisation process to look at history on a grand scale. We are moving into the era of big data newspaper studies.

Big data newspaper studies have come about through a combination of large-scale digital resources and a growth in analysis tools. Most will be aware of OCR (optical character recognition), the mechanism by which archival texts can be converted into machine-readable texts by converting what a computer sees as an image (i.e. the arrangement of letters on a page) and matches these to letters that it knows. It is an imperfect science, because OCR can struggle to work with older forms of types and deteriorating page originals, but levels of accuracy continue to improve as new OCR software is developed, and the results are generally satisfactory – that is, most of the time a researcher will find what they are looking for, if it is there to be found.

But added to this are software tools that can extract further sense from the raw data set that generated by OCR. The field of what is called Natural Language Processing, by which computer come to understand human text and speech, includes the extraction of keywords, or named entities, and the matching of these to controlled lists of terms (such as DBpedia), further mapped to geographic areas and time periods, which enables researchers to undertake controlled, thematic analysis of large historical datasets. Our archive of words yields patterns of behaviour with much to tell about our past selves.

This is the theme of a major project undertaken by the Intelligent Systems Laboratory at the university of Bristol, led by Professor Nello Cristianini. As described in their paper ‘Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals‘, the project worked on a corpus of newspapers digitised from the British Library’s collection by family history company Findmypast for the British Newspaper Archive website. The figures involved are huge. The project analysed 28.6 billion words from 35.9 million articles contained in 120 UK regional newspapers over the period 1800-1950, which they calculate forms 14% or all regional newspapers published in the UK over the period.

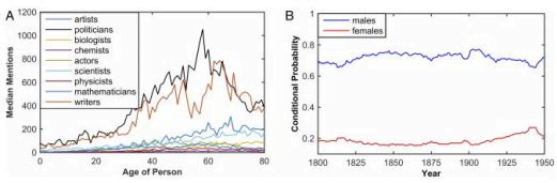

The project then used this study to explore changes in culture and society, determined by changes in the language. It looks at changes in values, political interests, the rise of ‘Britishness’ as a concept, the spread of technological innovations, the adoption of new communications technologies (the telegraph, telephone, radio, television etc), changing discussion of the economy, and social changes such as mentions of men and women, the growth in human interest news and the rising importance of popular culture. It is the stuff of multi-volume histories of the past, boiled down to eye-catching graphs.

This does not mean that we thrown away those multi-volume histories, however, The researchers are at pains to point out that such data analysis is an inexact science, with many caveats needed to explain how the entities have been arrived at and with what degree of caution they should be treated. The data derived from such tools can only work where it is supported by traditional studies, to gain the richer understanding of what happened. The machines may have taken the natural language of humans and converted it into data, but the results need to be converted back into human language to offer real understanding.

So it is that some of the results of the project yield results that may seem obvious. We could have guessed beforehand that the newspaper archive would show an increase in discussion of popular culture subjects, that politicians are more likely to achieve notoriety within their lifetimes than scientists, or that there was a rise in coverage of the Labour Party from the 1920s onwards. But the analyses reinforce through data what we have previously inferred through study, while discoveries such as the term ‘British’ overtaking the term ‘English’ at the end of the 19th century, or the decline in terms associated with ”Victorian values – such as ‘duty’, ‘courage’ and ‘endurance’ – call for new studies to explore these things further.

The project is at pains to point out the importance of using newspaper archives. Previously we have had big data analyses of millions of historical books, most familiar through the Google Ngram Viewer. This has caused controversy among some scholars, because of the unevenness of coverage of topics in books, and the limitations of merely counting words and making them searchable again. Opening up newspaper archives for comparable analysis widens the amount of content available, arguably with greater reliability overall, and now with tools to make analysis that much more scientific. The use of controlled terms will also enable the analysis across different datasets – so, books and newspapers, but also other news forms, as subtitle extraction and speech-to-text technologies now start to make our television and radio archives available for similar and shared analytical studies. Our big data is only going to get bigger.

There are limitations to this use of newspaper archives. The quality of OCR varies not only according to the original newspaper, but according to the microfilm where this has been used instead of print. Digitisation is quicker and cheaper this way than digitising from print, but older microfilm can be photographically poor, leading to inferior OCR (though there are promising tools appearing for improving poor OCR). The British Newspaper Archive is made up mostly of UK regional newspapers, because the main nationals have often been digitised by their current owners and are available separately. How different was the discourse in newspapers based in London from those around the rest of the country? That has to be the subject of another major study.

The British Library has been engaged in its own big data analyses of newspaper archives. BL Labs is an initiative designed to support and inspire the public use of the British Library’s digital collections and data in exciting and innovative ways. It has facilitated several studies of British historical topics through the digital newspaper archive. These include Bob Nicholson of Edge Hill University’s study of jokes in Victorian newspapers, with the concept of the Victorian Meme Machine (automatically matching jokes to an archive of contemporary images); Katrina Navickas of the University of Hertfordshire’s mapping of nineteenth century protest; and Hannah-Rose Murray of University of Nottingham’s tracing of black abolitionists in 19th century Britain. A major user of our newspaper data is M.H. Beals of Loughborough University, who is researching how ideas travel across the historical news media, creating new insights through understanding newspaper archives as structured data.

Such projects are just the start. The availability of large-scale newspaper archives in digital form, and the data derived from such archives, enables us both to seek answers to traditional questions more quickly, and to start asking new kinds of questions. The latter is the great challenge that newspaper data offers. We need to come up with new questions, because the technology enables us to do so, and because it may question what we previously thought that we knew. As the data from their archives comes more readily available, and more easily usable by the non-data specialist, so we will find that we have only just started to read the newspapers. We are going to find that they have much more yet to tell us.

Links:

- All of the regional newspapers used in the University of Bristol project are available at www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk (subscription site, free to use at British Library locations)

- The paper ‘Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals‘ is freely available in PDF format from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (PNAS)

- Secondary data from the project, in the form of yearly n-grams and entities, is freely available to download from http://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/dobuvuu00mh51q773bo8ybkdz

- A book by Paul Gooding on the issues surrounding the digitisation and use of newspaper archives, Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age, is to be published shortly by Routledge

This post was originally published on the British Library’s The Newsroom blog on 11 January 2017 and is reproduced here verbatim (with a few typos corrected)