This is the text of a talk I gave to a research event on newsreels at CIAC research centre, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, on 9 February 2017. I’ve also published it as a PDF, with footnotes instead of hyperlinks. In the original talk I ended with eight reasons for using newsreels to study history, but the number has now grown to ten.

It is unclear who it was who first said that newspapers form the rough draft of history. Though the words are often associated with Washington Post publisher Philip L. Graham in a speech he gave in 1963, he was only referring to an idea that had been around for some time. We can trace references to it back to the early 1900s, sometimes saying that newspapers formed the rough draft, sometimes more broadly referring to ‘news’ or ‘journalism’. What is certain, however, is that while the relationship between newspapers and the writing of history is commonly understood, the same cannot be said of newsreels. The aim of my talk is to ask why this is. What is the relationship between newsreels and history?

Newsreels, in case you needed reminding, were one of the major news media of the twentieth-century. They were shown in practically every cinema across the globe, occasionally in dedicated news cinemas of their own, but chiefly as part of the general cinema programme. In 1951, when newsreels were probably at their peak, it was estimated that there were 210 million spectators worldwide attending one of 100,000 cinemas every week, or one tenth of the global population. Almost all of them would have seen a newsreel.

But somehow the newsreel, as far as the history of news is concerned, has become the forgotten medium. It is difficult to find any general guide to news or journalism history that mentions it. There is a standard news media history timeline which goes from newspapers, to radio, to television to the Internet, and newsreels – a medium which existed for decades and influenced the worldview of hundreds of millions of people – are not there.

Of course, what is noticeable about that news media timeline is that none of the older media were superseded by the newer media. Radio did not kill off newspapers, television did not kill off radio, and despite the all-pervasiveness of the Internet we still have the news in newspapers, on radio and television. We have simply added to the richness and complexity of how we are informed about what is going on right now.

But the newsreels died. They were established in the 1910s, had passed their peak by end of the 1950s and had disappeared from most cinema screens across the globe by the 1970s. They had outrun their usefulness as a news medium. But what of their usefulness to history?

The importance of newsreels to the study of contemporary communications was recognised quite early on. In 1937 the American educator, Edgar Dale, an important figure in promoting the use of audiovisual media in education, wrote an article entitled ‘The Need for Study of the Newsreels‘ [link to subscription site]. Dale noted that there had been criticism of the newsreels in various journals, usually relating to political bias or for a tendency to favour unimportant stories or to ignore those that commentators deemed more important. But there had been no published study on how to approach the newsreels as a public phenomenon. To understand, and to find value in the newsreels, it was important first to define what they signified. Dale proposed three methods of approach.

First, a study of all the factors at works which led to the acceptance or rejection of stories for release in a newsreel, or the nature of the commentary that accompanied it. This would require knowledge of who owned the newsreels, their affiliation with industrial or political concerns, ‘a study of all forces impinging upon and influencing the production of the newsreel’.

Secondly, a careful study of the composition of newsreel content, classifying content by subject and measuring the treatment of subjects by length and the tone adopted by the commentary.

Thirdly, a study of the effect of the newsreels upon their viewers, in terms of ‘information, attitudes, emotions, and conduct’. Dale cites the example of the Payne Fund studies into the influence of cinema in general upon audiences, particularly children, which had attracted much interest from sociologists.

Dale then provides a rudimentary analysis of American newsreel subject matter, comparing 1931 to 1935, and concludes that while the newsreel was undoubtedly influencing the nature of American public opinion, concrete experimental evidence of that effect was still lacking.

There is much that can be criticised about Dale’s short paper. He says nothing about the number of cinemas, little about different kinds of audiences, and nothing about the cinema programme of which the newsreels formed only a part. He assumes that the longer a story was the greater influence it must have, which sometimes may have been so but never absolutely so. He views the audience as passive receptors, unquestioningly accepting all that is put before them – a dubious generalisation at best. He makes no comparison of the newsreels with other news media, saying nothing about a more complex model in which newsreels would be understood alongside other forms of information and diversion that collectively could influence an audience’s view of the world.

Nevertheless, Dale sets out a practical plan for comprehending the phenomenon of the newsreels, based on forces that influenced production, an analysis of content, and an analysis of reception. It stands as a good model for the study of newsreels, even to this day. He does not talk about newsreels and history, because newsreels were then still actuality, but the method could be applied by the inquiring historian.

Dale’s call for a systematic study of the newsreels was not properly taken up until 1951 with the publication, by UNESCO, of Peter Bächlin and Maurice Muller-Strauss’s Newsreels Across the World. This exceptional survey understood the importance of the newsreels on a global scale. The authors stated in their introduction:

The news film … is a universal means of mass communication and one of the most powerful. Pictures can be understood by every spectator, who sees for himself the news events they portray. Hence the importance of news films in enabling men and women to acquire information, as they are entitled to do, and to participate in all the developments of their time. Hence also the importance of newsfilms as a potential aid – or threat – to understanding between men and between nations.

The survey considers the history and characteristics of film as a vehicle for news; the state of the world newsreel industry, both in production and distribution; the composition of newsreels, the economic and technical factors that drove them and their political and social implications; and their relationship to television news and film magazines. They undertook a detailed study of newsreels in five countries: France, Uruguay, Egypt, India and the United States, and provided a wealth of tables, graphics and illustrations, include a country-by-country survey of existing newsreel services.

For Portugal, for example, it reported that a country with a population of 8.4 million people had 431 cinemas offering a total number of 242,000 seats, catering for 19.9 million visits per year. The leading newsreel producers were Sociedade Portuguesa de Actualides Cinematograficas, producers of Jornal Portgues, and Poper Filme, which produced stories for the American Universal News. The primary sources for news films imported from abroad were Paramount, MGM, Fox and Universal in the USA, and Actualitiés Françaises and Eclair Journal in France. The average length per issue was 300 metres, the number of issues per year twenty-five. The average number of copies produced per issue was only four, nearly all cinemas showed a newsreel, and censorship was in place. Editions were exported to Spain, Brazil and the USA.

Newsreels Across the World is a testament to the huge extent of the newsreels, and so by logical consequence there great importance for the understanding of twentieth-century history. It shares Edgar Dale’s concerns about the influence the newsreels had, both in the presentation of the stories they showed, and the stories that they gave less attention to because of their emphasis on entertainment. It adds concerns about the lack of opportunity for the audience to react to what they had seen, or to provide feedback to the newsreel producers, in sharp contrast to the state of things with newspapers. The authors state:

It is undoubtedly true that the speed with which newsreel items follow one another scarcely gives the spectator time for reflection, Therein lies precisely the tremendous suggestive power of each item. In order to follow the picture, the spectator must concentrate his attention that all other reactions are thrust into the background. And, even if he has a critical mind, he has no means of comparing or verifying the information presented unless by chance he was an eye-witness of the event itself. It is impossible to verify a presentation at screening time. The film carries its own authority, representing events that have actually happened; all these factors add to the conviction with which newsreels speak.

Whether one agrees or not with this line of argument – it says nothing about whether the audience member came to the screening already informed about the news story, though this was often the case if they were a newspaper reader – it establishes a powerful case for the study of the newsreels. They demanded a critical right of reply.

The next paper of importance came at a time when newsreels were on the wane, and becoming a part of history. Sir Arthur Elton, a British documentary filmmaker, in 1955 wrote an essay entitled ‘The Film as Source Material for History‘ [link to subscription site]. This addresses the opportunity for using not just newsreels but any sort of actuality film, for a variety of historical purposes. Elton says relatively little about what those historical purposes might be; instead he sets out the different kinds of material that ought to be of importance to the historian, and some of the challenges involved in managing them. He stresses the existence of newsreel libraries, but is less than flattering about the newsreels themselves, saying:

For at least the first thirty years the content of the newsreels was determined mainly by the passing fads and fancies of the time. The reels were there to entertain, and serious topics were usually treated unseriously or avoided.

Elton’s preference for ‘serious history’ overlooks the fact that a focus on fads and fancies can be very useful in understand the popular consciousness, and he does admit that there were some ‘notable exceptions’ which had treated serious news with the solemnity he preferred.

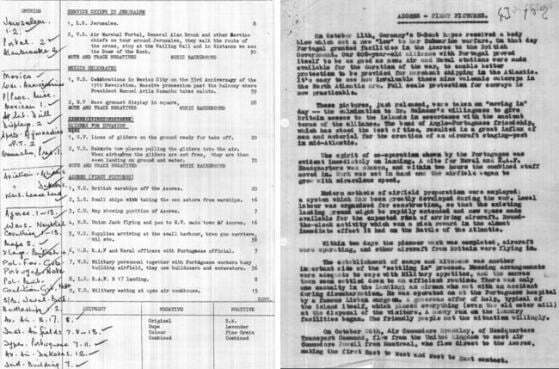

Elton’s paper sparked an interest in film as history in Britain, which led eventually to a particular focus on newsreels as a tool for historical investigation in that country. It was another filmmaker, the director Thorold Dickinson, who took things to a practical stage after he became Professor of Film in the 1960s at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. In 1969 Dickinson established the Slade Film History Register, a collection of documentation about film sources of use to historians. At the heart of the project was an attempt to build as comprehensive a collection of possible of newsreel issue sheets, the records of each issue put out by British newsreels from 1910 onwards, and to provide a classified index of these.

The Slade Film History Register answered a growing need. The BBC’s television series The Great War, broadcast in twenty-six parts in 1964, had had a massive impact, not least through its powerful use of actuality film to tell the story of the First World War. However, many questions started to be asked about the use of such footage, most notoriously the use of fiction film clips posing as actuality, and the editorial decision to flip some footage so that the Allies were always attacking from the left, the Central Powers from the right. Academics started to ask questions about how we should understand what was being projected to us, what its relationship was to historical truth. To the problems that the earlier studies had raised about the newsreels’ relationship with their audience were a new set of problems surrounding the re-use of newsreels for the presentation of history. The newsreels were now an important subject of study.

The Slade Film History Register assisted filmmakers, notably the team that produced ITV’s The World at War series, broadcast in twenty-six parts over 1973-74, on the Second Wold War. It supported university courses, and gave encouragement to a number of academics who became fascinated by how film, and particular newsreels, could serve the purposes of historiography. One of these academics, Nicholas Pronay, wrote two seminal essays in 1971 and 1972 on British newsreels in the 1930s, the first on ‘Audiences and Producers‘ [link to subscription site], the second on ‘Policies and Impact‘ [link to subscription site]. Pronay’s methodology does not differ greatly from that first proposed by Edgar Dale back in 1937, but he enriches it with depth of argument, rigour, extensive examples, and zeal. For Pronay, the newsreels are vital to the understanding of the social history of their times – not always to be trusted, but never to be ignored by anyone serious about understanding how ideas are formulated, communicated and shared. He places great emphasis on understanding the mechanics of newsreel production, and raises the challenge of understanding exactly what effect they had on audiences. He writes:

[T]hey are records of what the public was told about the events, the politicians and the policies of the day. It is as records of the media of public information, in the century of the common man, that they are of historical importance and utility. It is in the size, social composition and the attitudes of the audience of the newsreels that the strongest case for studying them is to be found.

The Slade Film History Register transferred to an educational body, the British Universities Film Council, in 1975. From there it flourished still further. The newsreel issues were published as a set of 275 microfiche in 1984, and I can remember as a young film archivist first coming across this extensive record of our past recorded on film and marvelling at the opportunities it promised. Three volumes of a Researcher’s Guide to British Newsreels were edited by James Ballantyne, between 1983 and 1993, and in 2000 the entire catalogue of 160,000 British newsreel stories from 1911 to 1979 was published first on CD-ROM and then as an online database, the British Universities Newsreel Database – now known as News on Screen.

I headed the British Universities Newsreel Database from 2000 to 2007, during which time we added a great deal more to it, in particular 80,000 digitised documents, include shot lists and commentary scripts, 25,000 extra records for the magazines films that were produced alongside the newsreels, and links to the digitised films. The arrival of the Internet, and then of increasing bandwidth, meant that the British newsreel libraries, which were still active commercial concerns, started to appear online. Linking up our records to theirs was not always easy, but what emerged was the researcher’s dream – a consistent and almost comprehensive register of newsreel issues, accurately identified by release date, title, company , issue and story numbers, accompanied by key documents in digital form, and with the newsreels themselves instantly playable. What would have taken a very determined researcher months of hunting, at no little expense, could now be discovered at the click of a mouse in one place, immediately, wherever they might be, and for free.

But what happened to the academic study? If anything, over that same period things have gone into reverse. The more that resources have been made available online, the less has been the study, and appreciation of newsreels in that same period. The generation of academics who were first supported by the Slade Film History Register, such as Nicholas Pronay, Anthony Aldgate, Paul Smith and Arthur Marwick, were not succeeded by a generation of academics with anything like the same understanding or sense of urgency. There are researchers around the world today who are interested in the newsreels, as this event alone proves, but they often work in isolation, and in the face of some ignorance. I found it telling, for example, that a recent, fine article by R.W. Purdy, on Japanese wartime newsreels [link to subscription site], for the Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television, felt it necessary to spend two pages explaining to its readership what a newsreel was. How have things come to this?

Newsreels are everywhere. They are omnipresent on the Internet, and their footage is continually reused in historical television programmes. They inform our picture of the past as much as they informed audiences’ view of the present in their heyday. Take British Pathé, for example. This British newsreel library, representing sixty years of production, or 3,500 hours of film, was published for free online in 2002, part-paid for by lottery funding. The archive was then made available in its entirety on YouTube in 2014, where its most popular films have gained millions of views. British Pathé also did a blanket deal with the BBC, the result of which is that Pathé newsreels are continually used on BBC programmes when a quick illustration of the past is required. British Pathé has become, for many, how the twentieth-century past is seen.

Despite this ubiquity, there is a general ignorance about what the newsreels once were. The generation of academics who wrote with such urgency about newsreels in 1970s had grown up with them. They had experienced them in the cinemas, then seen them translated into archive footage on history programmes. They understood the history behind the history.

What was their advantage, however, should not be our excuse for neglecting the newsreels. It is the historian’s responsibility to comprehend, to answer questions with all of the materials relevant to a particular enquiry, not simply those materials with which they are most familiar. The newsreel is not always easy to understand. It is a film medium, and the majority of historians have been suspicious of film as a form of evidence, and uneasy when it comes to referencing it as part of an enquiry. Historians like to work with words, because words are what they use. Pictures ask too many questions, and are too elusive in their meanings.

The newsreel is a news medium, but one not quite like any other news medium, so that it fails to fit comfortably into the critical concepts that commonly apply to the news. The need for the newsreel to entertain first, its subservient position as part of a cinema programme, the dependency it had on other news media, particularly newspapers, to indicate full meaning, all require extra effort of comprehension.

So is the newsreel worth that extra effort? Absolutely it is. Newsreels are central to our understanding of the social history of the twentieth-century, because the cinema that they inhabited was central to people’s lives. That question of the audience, which Edgar Dale, then Bächlin and Muller-Strauss, and then Pronay raised, but never quite answered, is what makes the newsreels so compelling. They are a mystery that has not been properly answered as yet. Just how did the newsreels appeal to their different audiences? Were they seen as a phenomenon in isolation, or did audiences comprehend them as part of a nexus of news provision that incorporated newspapers, radio and television? Did the propagandist newsreels of the era have the influence on people’s thinking that their sponsors imagined that they did? What does it mean – as various polls at the time demonstrate – that the newsreels were popular? What is meant by popular news? What gap in people’s lives did the newsreels fill? Above all, what do we learn from the newsreels by understanding their audiences first?

E.H. Carr, in his book What is History? defines history as being “an unending dialogue between the present and the past”. Carr defines history in a variety of ways, seeking a balance between objectivity and selectivity, but that relationship between past and present is vital. History is the present’s interpretation of the past. It changes as we change. For the newsreels, this means that they must have a relationship with the present, they must be meaningful and useful to us. It is not enough simply to know when a newsreel was filmed, when it was released, by whom, at what length, and so on. The newsreels must strike us as being indispensible, because they add depth to the enquiries that are important to us today.

So, why use the newsreels for the study of history? I have come up with ten main reasons. They do not cover every possible use, of course, but I hope they are helpful nonetheless.

1. Because they were there

The newsreels recorded actuality, in all its simplicity and complexity, and we can never go back in time to capture those scenes, and that outlook, again.

2. Because they influenced, and were meaningful

The newsreels had a profound influence on the outlook of millions, expanding their sense of the world, establishing lessons whose implications we have yet fully to fathom.

3. Because they are key to understanding what was popular and understood

The newsreels fed off a popular sensibility. They were at their most successful when they expressed what audiences understood, and watching them again helps us recover the world of that audience.

4. Because they can either confirm or counteract the evidence of the word

Newsreels can provide evidence of what happened or what was communicated, sometimes where written sources fail to do so.

5. Because they are an indivisible part of how news was transmitted

The newsreels did not exist in isolation – they were a part of a complex system of news provision that is a characteristic of the modern era.

6. Because they can be reused to portray the past

Newsreels are a tool for the history filmmaker, marvellous for what they chose to film, exasperating for what they decided to leave out.

7. Because they are reused to portray the past

Their re-use in history programmes and online, usually with little context, and all too often presented as depicting something that they did not depict, demands scrutiny in the name of historical truth. We are being lulled into accepting the newsreel archive at face value.

8. Because the presence of the newsreels changed the news

Before the newsreels arrived, the only form of news available was newspapers. The arrival of newsreels in 1910 introduced variety and choice, triggering the multi-media, multi-platform news world that we enjoy today.

9. Because their relationship to the truth is particularly relevant

In a world of post-truth and alternative facts, the newsreels’ own selective approach to the truth provides a useful lesson from the past.

10. Because they remind us of the elusiveness of the past

Nothing like the newsreels will ever be made again. Banal and outrageous, straightforward and mystifying, they demand answers that we may never be able fully to provide.

But that does not mean that we should not keep on trying. Newsreels are as much the rough draft of history as are newspapers. They must always have something in them that we recognise, that makes us want to find out more.

Links:

- Peter Bächlin and Maurice Muller-Strauss’s Newsreels Across the World is available in its English edition in PDF form from UNESCO

- For a history of the Slade Film History Register and its successor newsreel research resources, see Nicholas Hiley and Luke McKernan, ‘Reconstructing the news: British newsreel documentation and the British Universities Newsreel Project‘, Film History, Volume 13, pp. 185–199 (2001)

- The News on Screen database, which comes with extensive background information on British newsreels, is available from Learning on Screen (previously known as the British Universities Film & Video Council)

- Some online newsreel libraries include British Pathé, British Movietone News, Gaumont Pathé Archives (France) [requires registration], Deutsche Wocheschau (Germany) [no longer open to new logins], Archivio Storico (Italy), Australian Screen, Universal Newsreels (Internet Archive) (USA).

Luke- Excellent essay on Newsreels. I found it most interesting. As someone who has used them in research quite a lot, it is interesting to note the different color and textures of the subject matter and the story they were working to tell. Sometimes it is just an actual “Stand Alone” event but at other times it turns out to be part of a much larger picture. In these cases it takes much more commitment on our part to get to the essence of the story. They tend to be our last real tangent part of “living breathing history”

Hi Buckey, glad you like it. Perhaps an eleventh reason might be “Because the newsreels are so much more varied and richer than their critics would have you believe”.