![David Jones, Human Being, 1931 [a self-portrait] © Trustees of the David Jones Estate](https://lukemckernan.com/wp-content/uploads/davidjones_humanbeing1931_0.jpg)

To Pallant House Gallery at the weekend, in Chichester – the first time I’ve been to this rather fine gallery made up of a Queen Anne house with modern extension. It’s primarily devoted to modern British art, with fine examples of Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson, David Bomberg, Ivon Hitchens, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Michael Andrews, Richard Hamilton et al, plus near neighbours Sean Scully and Jack Yeats. All very much my sort of thing, and I can warmly recommend the bookshop, not least for incorporating a significant second-hand section.

I was there to seen an exhibition by one of my favourite painters, David Jones. The exhibition is entitled Vision and Memory, and it runs until 21 February 2016. It is curious why Jones is not better known than he is, either as a painter or as poet. Perhaps it is hazardous being accomplished in more than one artform, since those who are troubled by such things don’t know where to put you, though it has never upset the reputations of William Blake, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, or Michelangelo for that matter.

But if you ask those who consider themselves well up on British twentieth-century literature it is surprising how few have heard of Jones, let alone read his great long poems In Parenthesis or The Anathemata, and still more startling that his art should be as little known as it is, since it is that much more approachable.

Jones is someone whose art is immediately recognisable and uniquely his own. It was conceived of by him, and has been copied by no one. His frequent subject was the mythological and spiritual made manifest in the real. His images, which are mostly watercolours, present seemingly simple scenes overlaid with historical and mythological references (Roman, British, Welsh, Norse) and Roman Catholic imagery in a manner that shows ideas in and out of the surface. Jones was someone who could not see a landscape without seeing the history that underpinned it, and saw life governed by the spiritual. The above painting, Vexilla Regis, once of his most noted works, exemplifies this. It brings together Christian (three trees = Christ’s crucifixion), Roman (the third tree is akin to a Roman column) and Norse (the holy tree Yggdrasil) in a highly complex concatenation of ideas which could could keep an art historian busy for years (and has done).

The beauty of Jones’ paintings is that these things matter and yet at same do not matter. You do not have to be a Roman Catholic apologist or a classical historian to get the most out of them. The import is in the visual, the palimpsestuous overlaying of ideas. The pleasure in viewing them need not be impaired by the need to interpret them. It is much the same as with his poetry, which is similarly allusive and richly informed by history and religion, yet can be read as journeys of a mysterious beauty, without need always to be checking the footnotes.

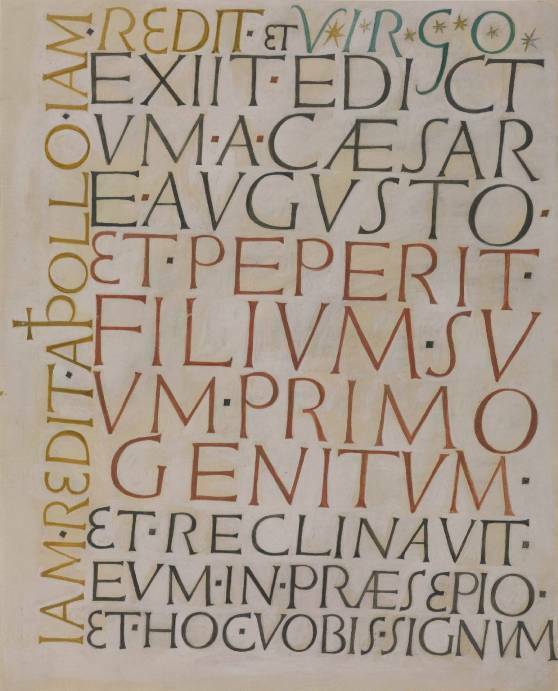

It is appropriate that perhaps Jones’ greatest work is his calligraphy, bringing the poet and artist together to create words as art. His Latin inscriptions and his book title page designs employ Anglo-Saxon and Roman lettering in a highly distinctive and appealing form. The look like writings uncovered from two thousand years ago, or else produced yesterday. Above is ‘Exiit Edictum’, a combination of lines from St Luke’s gospel and Virgil’s fourth Eclogue, both on the birth of Christ. It is not just the idiosyncratic arrangement and spacing of the letters, but the use of colour to highlight significant words that makes his inscriptions so haunting. You don’t have to know the language to have an understanding of them (though a little Latin may help). The primary appeal of his art is to the senses.

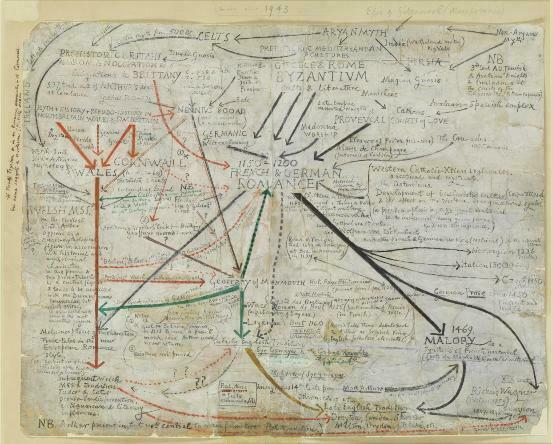

His subject overall is what the medievalists called ‘the matter of Britain’, which meant stories of Arthurian legend, as opposed to the matter of France (stories of Charlemagne) or the matter of Rome (classical stories). He drew on the French and Roman traditions, but his heart lay in British mythology, and particularly Wales (he was of Anglo-Welsh parentage, though he lived most of his life in London). Welsh history and mythology enraptured him. The soldiers of whom he writes in In Parenthesis are Londoners and Welshmen of 1916 but also Arthurian figures whose thoughts and actions float between time present and time past. He finds the heroic in everyman. The marvellous ‘Map of themes in the artist’s mind’ (also known as ‘Chart of sources for Arthurian legends’) shows the great interconnectedness of his thinking, drawing the lines of association between Malory, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Byzantium, Celtic myth, Welsh and Cornish tradition, and Christianity. You don’t need to understand it all, just to appreciate the vision of someone who thought that he could.

Not all of David Jones’ art is so consciously multi-layered, though even the simplest of landscape or portraits are rich in tantalising wisps of line, colour and decoration that suggest that other, inner life. Perhaps his standing in the worlds of art and poetry is not as high as it could be because his work is seen as difficult, catering only to the intellectual. All you have to do is attend an exhibition of his to discover that this is not true. It is beautiful and mysterious art that instantly captures the imagination. It does what art should do, which is to lead us beyond the surface of things. Do go if you can.

Links

- The ‘Vision and Memory’ exhibition at Pallant House Gallery runs until 21 February 2016. There is a complementary exhibition at the nearby Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft on his paintings and drawings of animals, which runs until 6 March 2016

- The essential book on David Jones is The Paintings of David Jones by Nicolete Gray

- Thomas Dilworth’s David Jones in the Great War is a fine account of Jones’ profoundly formative experience on the Western Front – to be read in conjunction with his great narrative poem about the war, In Parenthesis

- There’s a David Jones Society (whose website is in urgent need of updating) and a North American Society (whose site is marginally more up to date)

- There are two illuminating documentaries on David Jones on Daily Motion

One thought on “David Jones and the matter of Britain”