Lucifer (2014), directed by the Belgian filmmaker Gust van den Berghe, is a remarkable work of art. Loosely based on the 1654 Dutch play of the same title by Joost van den Vondel, it tells of the visitation of the Devil to a present-day Mexican village, bringing sin and sorrow in his wake, leading to the loss – or perhaps regaining – of paradise (the play is believed by some to have been an influence on Milton’s Paradise Lost). The film, which is the third in a trilogy of religious-themed works from the director, mixes the worldly with the otherworldly in an extraordinarily effective way. It is beautiful to look at and to listen to, hauntingly performed by local amateurs, and often deliciously funny.

Trailer for Lucifer (2014)

But what is most remarkable about the film is its circular frame. Until its final shot, showing a return to the everyday, the film’s screen shape is a circle. Abandoning over a century of rectangular film framing, Lucifer shows its world in the round. Everything is framed according to the demands of the circle, which includes not only how the images are composed, but how the performers are seen to interact, even the sound design. The technique has been named Tondoscope by the director (from the Renaissance term for a circular work of art), and at key points involved filming into a conical mirror to capture action in 360-degrees. The screengrabs below show the gathering of clouds over the Parícutin volcano, and the scenes where the devil leaves after having seduced Maria.

This is no gimmick. The aesthetic choice is designed to reflect a faith-based view of the world, in which that faith is all-encompassing. Specifically it reflects that holistic world picture which was fundamental to the 16th century’s understanding of itself (the Elizabethan World Picture, which I have written about before now) but which started to fall apart in the 17th (in which Vondel’s play was written). In such a world the cosmic overrides the earthly, as the assumed perfection of creation finds its logical expression in the perfect shape of a circle.

Gust van den Berghe cites examples from the history of art where the images is circular, including works by Bosch and Pieter Brueghel. He also references Dauguerrotype portraits and pre-cinema optical devices, such as the Praxinoscope and the magic lantern, whose images were frequently circular projections. He writes:

These magic lanterns hold the true legacy of pre-cinema in them, as they were used in variety theaters with live piano music and sing-alongs, right before they were replaced by silent films. As the first of all these registered and reproduced images came in a circular form, one might say that this is their native shape as they pass through any lens or aperture hole, based on the construction of the human eye. It is only when man applies a masking to it that they get a constrained quadrilateral geometrical figure, for example 1:1, 4:3, 16:9, 2,35:1…

Other circular images existed – images seen through microscopes and telescopes, kaleidoscopes. So there was a rational aesthetic choice and a clear pre-cinema history of circular images upon which to draw, but what about circular cinema? Has it always been the squares and rectangles of 1:1, 4:3, 16:9, 2,35:1 and so on?

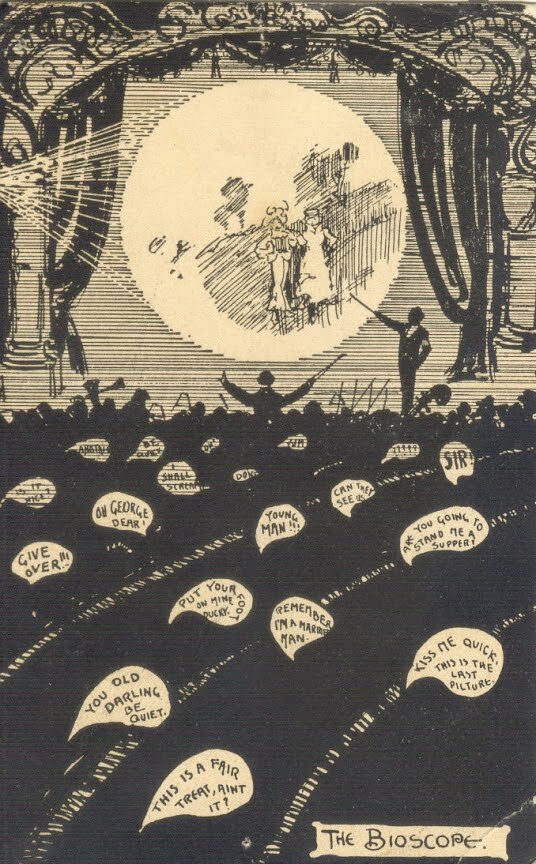

Well yes, but with a qualified no. In the first years of cinema there was confusion among some artists illustrating the phenomenon as to what they were actually seeing. Still thinking of how magic lantern projections often worked, on occasion some depicted film shows as though they also employed circular projection. The postcard above, from 1904, shows a Bioscope film show in a variety theatre, with a lecturer pointing out what was appearing on the screen, and the audience rather more interested in what they could get up to in the dark than the show. The projected film is shown as being round. Other such examples exist from cartoons and illustrations of the period. There were no circular film projections, but some imagined that they existed.

Animated gif of Wordsworth Donisthorpe’s circular images of Trafalgar Square in 1890, via Wikimedia Commons

W.K-L. Dickson’s Newark Athlete (1891) with its circular framing

But there might have been circular film projections, had things turned out differently. Some of the earliest film experiments, when successive image capture was being perfected but playback had yet to be worked out, featured round images. British inventor and political agitator Wordsworth Donisthorpe, very probably inspired by Kodak’s early (1888) circular snapshot picture format, took a proto-film of London’s Trafalgar Square in 1890, ten frames of which survive. W-K.L. Dickson, working in the Edison laboratories in early 1891 produced some strips of film with circular images, and Charles Francis Jenkins in July 1894 published some successive circular images with his Phantascope camera showing a man shot putting. The rules of how a film should look were not yet set, though soon enough Dickson’s use of a 4:3 frame on 35mm film would set an industry standard.

Circular projection could occur within the frame. With his mind still grounded to a degree in magic lantern practice, in 1898 the British filmmaker G.A. Smith made Santa Claus, in which a child in its bedroom sees Santa arriving on the roof of the house via a circular moving image in a corner of the frame. It is film in the round, albeit contained within a larger rectangle.

Thereafter film has, for the most part stayed horizontally rectangular. Vignettes and iris-out effects have been employed that change the screen image to a circle for a brief period, circular projections are used with the main screen shape for eye-catching effect (consider the Dr No title sequence, for example), and circular films have been used in some video installations, but until now – or at least as far I have been able to discover – there has been no attempt at a sustained piece of film shaped as a circle until 2014 and Lucifer.

But why are films (horizontally) rectangular? It seems an obvious aesthetic choice, but that is because we are familiar with it. Of course for film it is an inheritance from earlier artforms, ranging from paintings to poster to magic lantern projections. The screens that accommodated the new artform of cinema had been constructed to suit prior forms, which were in turn so shaped through long-held cultural conventions.

The rectangular picture dates back to Renaissance times. Edmund Burke Feldman, in his Varieties of Visual Experience, states:

The rectangular canvas is one of many possible shapes. But it dominates all others mainly because of the Renaissance convention that a picture is a window opened on the world and then painted by an artist. The convention has been so thoroughly absorbed by our culture that we are hardly aware of it, but it crops up in popular architecture as the “picture window”. The design of a wall around a scenic or pictorial opening is a strange reversal of history, because pictorial imagery has usually been subordinated to architecture – in mosaics, stained glass, murals, and large-scale tapestries. Painting tends to “obey” externally determined formats.

As with with paintings, so with the motion picture screen, though it is importance to note the change the the Renaissance brought about in the art object as a fixture in itself, rather than something to fill a space (as in those mosaics and murals). Art moved from wall to window. That window on the world (a concept introduced by Leon Baptista Alberti in his 1435 theoretical work De Pictura) generally presents the viewer with a horizon, with human figures placed within that picture, whose positioning creates the inherent dramatic interest. It usefully emulates how we comprehend what lies before us, how we scan the visual display for information. By such means do we understand where we are.

Film shape has therefore remained rectangular because of the art tradition that preceded it. The precise dimensions of those rectangles have changed, firstly because different interests wanted to promote a unique product, and then assorted widescreen variants to present film as a spectacular that could not be replicated on traditional television sets (it’s worth noting, by the way, that early television sets had curved or even entirely round screens because of how the cathode rays were bombarded at the screen, but the original image composition was rectangular – Academy ratio – so the viewer simply lost some of the full image). Nowadays such battles have settled down, and 16:9 is the aspect ratio of choice for home screens, and 1.85:1 in cinemas.

Video essay on vertical video by Miriam Ross

But our windows on the world are changing. The rise of videos shot on mobile phones has led to the rise of vertical videos – portrait rather than landscape. First viewed as an amateurish error, these are now starting to be accepted as a viable aesthetic alternative. YouTube now allows for vertical video on its Android app and serious compositions are being produced with the ‘new’ ratio – see the thoughtful video essay above.

Video explaining the technical background to Lucifer. Note for example the comments of the sound designer (around 6:30) on how the absence of left and right speakers means that he has to place sounds differently, in depth, resulting in a totally new dimension; and the DOP speaking (at 7.45) about how there is less narrative to work with, because the eyes no longer scan the image from left to right but instead the story is cut up into separate elements

So why not round cinema? Gust van den Berghe’s thoughts on filming in Tondoscope shows how what was orginally a cosmological, historically informed aesthetic choice, brought about changes in how the pictures were composed and how we read these in projection:

What comes to mind, is that if Tondoscope had the means of having a solid or holographic nature, it would probably be a ball or a sphere. This, because at the same time it will yield a very naturalistic and unhindered look on a scene, and also portray this scene as an event that happens in a bubble. Every scene that takes place that way becomes a happening that has its individual importance in time and space. A personage finding itself in this circular frame is regarded as isolated and has his world to himself, and accordingly, if one would circularly frame more people together, for a moment, they share experiences or a world.

This results in the effect that when we film in Tondoscope, and there is a scene where multiple personages partake, whenever a single person is framed, this person ends up extra isolated from the group when these shots are combined or intercut with other shots containing more than one personage, who then share more with each other than that one. The inter-human relationships seem emphasized by circling them. In general, in Tondoscope, the circle emphasizes every emotional relation between the personages and throws out a direct line to the viewer.

Whether this is absolutely so, only the viewer can decide. There are distractions that come with the circular video. Although the image is shown in the round, it is still presented to us on horizontal rectangular screens, because that is how our cinemas and home screens are constructed. There is a large amount of extraneous black space for our eyes to manage. We see not only the circle but the void that surrounds it. Moreover, our eyes are trained to read cinema in landscape format. We yearn to scan the horizon. We may fight against what Lucifer forces us to see.

Yet I think Lucifer wins the battle. The skill involved in its production, and the alignment of subject matter and technique, make us look in a new way and understand. It arranges things differently, and we as viewers must appreciate that. Whether Lucifer is a one-off, or if there will be other circular videos, it is hard to say. Van den Berghe may have claimed the format for his own, but there is enough in that suggestion of a distinctive way of portraying inter-human relationships and a directness to the viewer to indicate that others may want to explore the possibilities. Artworks have long since broken out of their frames to find shapes determined by the imagination rather than by architecture. Films can follow. Our windows are changing.

I would encourage anyone to see Lucifer if they can. It has just had two screenings at the London Film Festival, and is currently available on the arthouse video house site and Smart TV app Mubi for the next two weeks or so.

Links:

- The official site for Lucifer has a trailer, slideshow, director’s note and credits – all of it circular, naturally

- What is Tondoscope explains the director’s thinking behind his aesthetic and technical choices

- There is a handy illustrated history of Tondo art at Spacial Anomaly

- There is more information and thinking on vertical video by Miriam Ross on her Cinema Lives Cinema Loves blog

- Update link: I’ve been told about Roundness, a delightful website devoted to all things round, which includes some examples of videos made in the round and videos projected onto turntables

I’ve updated this post to include mention of Wordsworth Donisthorpe, with thanks to Stephen Herbert having pointed out to me what is undoubtedly the very first Tondoscope film (plus the Kodak connection).

And the trend continues. Another circular feature film has been made, the Chinese film I Am Not Madame Bovary (2016), whose circular image was selected apparently in imitation of willow pattern plates and the like. The circular frame is used for rural scenes; city scenes are square-shaped (so say the reviews – I’ve not seen the film as yet)