All we ever do is tell stories to one another.

Back in 1999 Sight and Sound magazine published a plot summary for the Blair Witch Project, as it does for all films released theatrically in the UK. Such plot summaries give the plain details of the plot of the film, as a matter of record, alongside the cast and credit details. Except that on this occasion they did not give the full plot summary. It ended with a row of dots, not giving away what happened when the heroine enters a basement with her camera. I found this really annoying, because of the lapse in standards for what was meant to be a source for future reference, and for how the magazine had kowtowed to the film’s publicity machine.

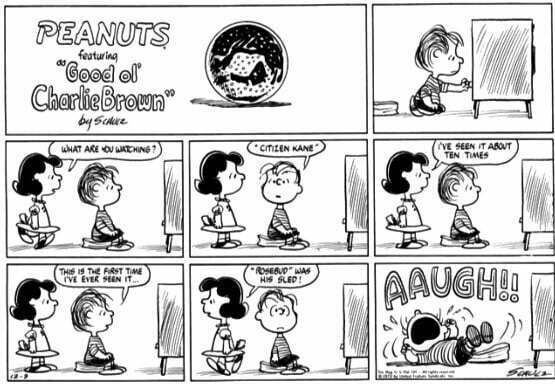

This lapse was – I think – a one-off, but it shows how certain films depend on attracting an audience through having some plot twist, or gimmick, which ostensibly becomes the chief reason for going to see it. “Don’t give away the ending – it’s the only one we have!” urged publicity for Hitchcock’s Psycho. The urge to know what happens next, and the sense of disappointment or even betrayal when some find out the answer before they have seen the film is powerful. The greatest crime a film reviewer can commit is to give away key plot details. Anyone writing about films online feels obliged to preface their comments with the warning that there are ‘spoilers’ ahead. And my question is, why does this matter?

In his 1927 book Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster sets out an understanding of how novels operate through seven such aspects: story, people, plot, fantasy, prophecy, pattern and rhythm. He begins with a now famous summary of different people’s view of the story:

Let us listen to three voices. If you ask one type of man, “What does a novel do?” he will reply placidly: “Well – I don’t know – it seems a funny sort of question to ask – a novel’s a novel – well, I don’t know – I suppose it kind of tells a story, so to speak.” He is quite good-tempered and vague, and probably driving a motor-bus at the same time and paying no more attention to literature than it merits. Another man, whom I visualize as on a golf-course, will be aggressive and brisk. He will reply: “What does a novel do? Why, tell a story, and I’ve no use for it if it didn’t. I like a story. You can take your art, you can take your literature, you can take your music, but give me a good story. And I like a story, mind, and my wife’s the same.” And a third man says in a sort of drooping regretful voice, “Yes – oh, dear, yes – the novel tells a story.” I respect and admire the first speaker. I detest and fear the second. And the third is myself.

Forster acknowledges that the story is the fundamental aspect without which the novel could not exist, defining it as “a narrative of events arranged in their time sequence” with but one merit, “that of making the audience want to know what happens next”. It is a primitive desire, he argues, the need to know what lies on the next page, the necessary structure on which the work of art is built, but not the art itself. There has to be a story for there to be meaning, but that is all. He differentiates story from plot, which he defines as “a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality.” He gives this example:

‘The king died and then the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’, is a plot.

This is useful, and seems reasonable. It shows us why, say, a detective novel may be considered a lower form of art, being driven entirely by the mechanics of what happens next, and tragic drama a higher form, where causality is all. But Forster then suffers an interesting lapse. Having earlier referenced the story-telling of prehistoric man and the means by why Scheherazade stays alive through story-telling because the sultan always want to know what happens next, he writes:

Consider the death of the queen. If it is in a story we say ‘and then?’ If it is in a plot we ask ‘why?’ That is the fundamental difference between these two aspects of the novel. A plot cannot be told to a gaping audience of cave men or to a tyrannical sultan or to their modern descendant the movie-public. They can only be kept awake by ‘and then – and then -‘ they can only supply curiosity. But a plot demands intelligence and memory also.

This reveals a lazy prejudice against the supposedly unthinking film audience, and it also undermines his argument. The film audience (and the readers of novels) almost never pins its hopes on the primitive mechanics of the story alone. It consigns formulaic genre works to the lowest form of cinema art – the B-movie that is just there to fill up some time in the auditorium. The cinema audience demands plausibility, which is the coming together of character, atmosphere and incident. Plausibility is hand-maiden to causality.

‘And then?’ and ‘Why?’ are not separate conditions, but the inseparable key to how we follow narratives. The need to know what happens next drives the urge to turn the page or stick around for the next reel. But we need just as much to be convinced that it is worth doing so, which means ultimately that what we are being offered is grounded in truth. How that truth is expressed may often lie in the artistry that Forster champions, but the essential feature of that artistry must be plausibility – truth to nature, be that in character, situation, description, philosophy or whatever. It is what makes any story worth telling.

Yuval Harari lecturing on imagined realities

Human beings need stories; they define what we are. We need to eat and sleep and socialise, but so do all other animals. Only humans tell stories, and construct their idea of the world through stories. Yuval Noah Harari, in his book Sapiens argues that what has made humans unique and successful as a species is their propensity for imagining things collectively. Human lives are governed by imagined realities – let’s call them stories – by belief in concepts such as gods, religion, nations, money, limited liability companies and human rights, which do not objectively exist. They are believed in because to live we need to believe. The story, a construct which puts a shape to life, which says that there is a beginning, a middle and an end, and says that what holds this thread together is reason or a set of rules which can be predicted to a degree, is fundamental to humans’ collective sense of themselves. Without stories we have no idea where we are.

This point can be illustrated by the story of Victor of Aveyron, the feral child captured in 1800, who is the subject of Truffaut’s classic film L’enfant sauvage (1970). Aged around nine when he was caught after having lived wild in a forest for a number of years, he was cared for and closely observed by French medical student Jean Marc Gaspard Itard. Unable to speak, seemingly indifferent to any kind of human interaction, trapped in a world solely of his own understanding, Victor was – as the philosopher Etienne Bonnot de Condillac, a great influence on Itard, wrote of another feral child – living in a continual present:

Supposing in order to try every hypothesis, that he had likewise remembered the time when he lived in the forest, it would have been impossible for him to represent it to himself but by the perceptions which he would have recalled to mind. These perceptions could be very few; and as he had not remembrance of those which had preceded, followed, or interrupted them, he would never have recollected the succession of the parts of this time … In a word, the confused remembrance of his former state would have reduced him to the absurdity of imagining himself to have always existed, though he was as yet incapable of representing his pretended eternity to himself but as a moment.

Victor had no sense of history, because he had no sense of others by which to measure such a sense of self. Theories of the development of the mind of a child stress the importance of narratives as a means for children to create worlds through which they come to understand themselves and human nature. Victor, robbed of a childhood and the company that should nurture it, understood neither.

This helps show how stories define what it is to be human. Not just written stories, but gossip, news, information, instructions, plans, events, games, competitions, and all forms of socialization. We digest experience and relay it to others as stories, with a beginning, a middle, and end, and a lesson to be learned. Without stories we are just a wild thing, lost in a forest.

All of which brings us back to spoilers. When I first thought to write this post I was minded to defend the use of spoilers, saying that those who are upset when plot points are given away may have a limited appreciation of art. Why things happened the way they did was more important that the plain what, and it was the function of the film or the novel to demonstrate the why, with the story simply being the structural means to achieve this. That’s what E.M. Forster was arguing.

But now I’m not so sure. There is something about the anticipation of what happens next that is an important aspect of how we determine truth. It’s there in the suspense, followed by the satisfaction of understanding. Knowing the ‘how’ before we appreciate the ‘why’ diminishes the latter. The two can only work together. Spoilers rob us of experience. I can’t promise that I won’t give away plot details in future writings, because to do so can look a bit too much like playing the filmmaker’s (or novelist’s) game for them. But I will try to understand the annoyance a little more.

Links:

- On feral children, see Michael Newton’s Savage Girls and Wild Boys (2002)

- On narrative and children’s development, see David Wood, How Children Think and Learn (second edition) (1998)