On 18 February 1814 Lord Byron got up and read his morning newspaper, a fact that we know because he recorded the action later that day in his journal:

Got up – redde the Morning Post containing the battle of Buonaparte, the destruction of the Custom House, and a paragraph on me as long as my pedigree, and vituperative, as usual.

George Gordon Lord Byron, Leslie A. Marchand (ed.), Byron’s Letters and Journals, (London, 1974), 3, p. 242, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=2113, accessed: 16 July 2014

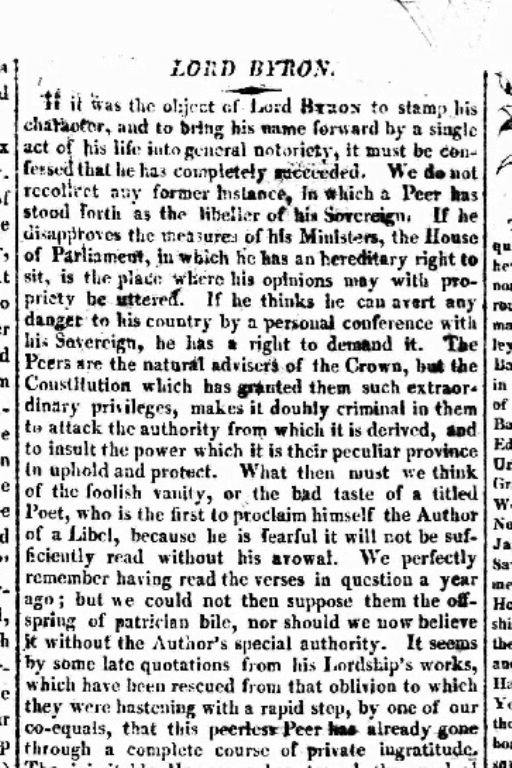

Sure enough, in the Morning Post for that date is a column attacking the poet, just as he would have read it:

The history of newspapers is usually written from the point of view of their producers, being a tale of owners, editors, writers, money and politics. What gets less attention is the history of newspapers viewed through its consumers. We are told about which classes bought which papers, we know about prices, and we know that newspapers in past centuries were read both privately and out loud to others. But of the readers and the actual experience of reading newspapers there is too little. How different sections of society have found their news, how they read it, understood, paid for it, shared it, and acted upon it, are hugely important, but many newspaper histories and reference books pay scant attention to those whose news it ultimately was (Andrew Pettegree’s recent The Invention of News is a notable exception). We have circulation figures and statistics, but it would be good to see people too.

So where to find out information on how people read newspapers in the past? A terrific resource is the Open University’s Reading Experience Database, from which the Lord Byron quote above comes. The Reading Experience Database (RED) is a project documenting the history of reading in Britain from 1450 to 1945 (there are allied databases tracing the history of reading in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands and New Zealand). The database contains some 30,000 records containing verbtatim texts taken from published and unpublished sources, including diaries, commonplace books, memoirs, sociological surveys, criminal court and prison records. Its aim is to document the “recorded engagement with a written or printed text – beyond the mere fact of possession”.

The fully-searchable database has been built up by both the project team and around 100 volunteers who have volunteered examples from their own reading and areas of interest (anyone can contribute if they wish). Each record gives the text that documents the reading experience, the date, country, time of day, place, type of experience (e.g. solitary or in company), the reader and their personal details, the type of text being read, and details of the source itself. Much of the evidence gathered relates to the reading of books, but there is also a substantial collection of testimony relating to reading newspapers.

Here, for example, is Thomas Carter, remembering his newspaper-reading and sharing habits in 1815:

Thus I became their [workmates] news-purveyor, ie. I every morning gave them an account of what I had just been reading in the yesterday’s newspaper. I read this at a coffee shop, where I took an early breakfast on my way to work. These shops were but just then becoming general… The shop I selected was near the bottom of Oxford Street. It was in the direct path by which I made my way to work… The papers I generally preferred to read were the “British Press”, the “Morning Chronicle”, and the “Statesman”. I usually contrived to run over the Parliamentary debates and the foreign news, together with the leading articles. …My shopmates were much pleased at the extent and variety of the intelligence which I was able to give them about public affairs, and they were the more pleased because I often told them about the contents of Mr. Cobbett’s “Political Register”, as they were warm admirers of that clever and very intelligible writer.

Thomas Carter, Memoirs of a Working Man, (London, 1845), p. 186, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=7619, accessed: 16 July 2014

This comes from Carter’s Memoirs of a Working Man (1845) and is a relatively rare example of working class testimony. Memoirs, journals and accounts in newspapers themselves were generally the preserve of the wealthier classes in the 17th to 17th centuries, so Carter’s account of how he read and the re-transmitted intelligence from a range of newspaper to his work colleagues is precious. However, the RED’s advanced search options allows one to refine searches by social type (servant, labourer, clergy, gentry, clerk / tradesman, professional, royalty / aristocracy), so here is a servant in an 1839 trial revealing his newspaper reading habits while giving evidence:

On Saturday morning, the 26th of January, I was reading in the newspaper of the loss of Mr. Platt’s plate, in Russellsquare – I went up to my master, and pointed it out to him; and, in consequence of his directions, I went down to the pantry to bring up the spare plate, and found it was gone – I suspected the prisoner, and gave information to the police.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, 27 April 2009), 4 Feb 1839, Trial of William Smith (t18390204-682), http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=24962, accessed: 16 July 2014

Nineteenth-century newspapers were read not only for news of public affairs, but for social affairs and gossip. On 24 October 1808 Jane Austen wrote from Southampton to her sister Cassandra:

On the subject of matrimony, I must notice a wedding in the Salisbury paper, which has amused me very much, Dr Phillot to Lady Frances St Lawrence.

Jane Austen, Deirdre Le Faye (ed.), Jane Austen’s Letters, (Oxford, 1995), p. 151, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=10383, accessed: 16 July 2014

From the previous century, here is James Boswell recalling how he was obliged to read out from the newspaper to Samuel Johnson, under the latter’s strict instructions:

“The London Chronicle”, which was the only newspaper he constantly took in, being brought, the office of reading it aloud was assigned to me. I was diverted by his impatience. He made me pass over so many parts of it, that my task was very easy. He would not suffer one of the petitions to the King about the Middlesex election to be read.

James Boswell, R.C. Chapman (ed.), Life of Johnson, (Oxford, 1980), p. 424, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=21084, accessed: 16 July 2014

From a later period, here is Harriet Martineau in a letter dated 1 March 1866, while residing in the Lake District, noting comments made about Matthew Arnold in the press:

Of course you have seen the squib on him in the “Examiner” (“Mr Sampson”). I saw it in a Liverpool paper. One sees him in almost every newspaper now. “D. News” rapped his knuckles a month since… and I see the “Times” did it yesterday.

Harriet Martineau, Elisabeth Sanders Arbuckle (ed.), Harriet Martineau’s Letters to Fanny Wedgwood, (Stanford, 1983), p. 266, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/record_details.php?id=9211, accessed: 16 July 2014

Here we see, as with Thomas Carter, how common it was to gain intelligence from a range of newspapers, as well as how the national titles were diffused across the country.

We gain from such accounts an idea of how newspapers were read, who read them, what information they expected to gain from them, how they analysed such information, and how they passed on such information. We see newspapers as a habit, and how they operated as part of the daily round. We see how public knowledge was communicated and how people understood their place in the life of the nation. We see the importance of newspapers as something experienced – which is crucial to understanding their function and history.

The Reading Experience Database is an excellent resource: clear, rigorous and easy to use. It is limited to actual evidence of newspaper reading. It does not include fictional accounts, which can be just as revealing of how newspapers were received. It is of course limited by what documentation is available and what its project team and host of volunteers have been able to find. It is selective evidence. Such accounts do not usually record how a newspaper was read, how it was handled, even how much time was spent in reading it. We do not see the visual relation of the reader to the newspaper. For that you need paintings or photographs. Which might be another project, at another time.

Post originally published on the British Library’s The Newsroom blog on 17 July 2014 and reproduced here verbatim