I’ve been thinking about news lately. At the British Library we’ve just piloted a television and radio news service, called Broadcast News, which has selected news broadcasts from May 2010 onwards taken from seventeen channels available on Freeview and Freesat. But the service can’t just stand alone. It has to join up with other news media. We hold the UK’s newspaper library, we’re on the verge of archiving UK web space, and we have radio news archives. How to join these all up – but, first of all, why?

It’s important to step back and ask what news is. This is a question that has intrigued me for many years, since I first started researching cinema newsreels twenty years or more ago. Many have defined news in differing ways, but the starting point from me was this description provided by Nicholas Pronay, saying why two films from 1895 qualified as news, one the Lumière brothers’ film of delegates at a photographic conference on 10 June 1895, and from the same month Birt Acres’ film of the opening of the Kiel canal:

These two films, in their separate ways, are indeed the archetypes of the newsfilm. They set out to interest a specific audience by reporting an event which had news value not because of the inherent pictorial interest of the subject, but because the audience was already interested, had already been conditioned to be interested in it. Pictures of soberly dressed Frenchmen disembarking from an ordinary riverboat on a very ordinary promenade were not intrinsically fascinating even to the average Frenchman. But if the audience was composed of people already interested in photography and if they were told that the pictures showed the arrival of leading French photographers at their annual conference, then these unexciting pictures would be invested with a significance, by the mind of the audience itself.

Nicholas Pronay, ‘Newsreels: The Illusion of Actuality’, from Paul Smith (ed.) The Historian and Film (1976)

This enticing definition cried out for simplification, so I had go in my first book, a history of a newsreel:

A newsfilm can be defined as an actuality item of current interest for a specific audience.

Topical Budget: The Great British News Film (1992)

By ‘actuality’ I meant a film depicting actual events, and deliberately did not attempt to measure the news value of actuality, prefeering to trust in the audience’s understanding of what was news to it, rather than the perception of a journalist or film producer. Over the years I’ve produced assorted variations on this when introducing the subject of newsreels, until I came up with this definition for a talk given at a Spanish conference last year, which discussed early newsreels but sought to locate them within a wider field of news production:

There are three factors that define news as news: from whom it comes, when it is delivered, and the audience to whom it is delivered. News is not an absolute – it is selected, described and published in a particular form by an identifiable producer, for we need to know from whom it comes to assess what sort of news it is. Then it has to be current, as far as possible of the day, because yesterday’s news is news no longer. The history of all modern news media is one of speed, wanting to get the intelligence about what has happened to a public as soon as possible. And then the audience is crucial to the definition of news, because what is news to one person is not necessarily going to be news to another. They have to be interested in it as news for it to be recognised as news.

‘Links in the chain: early newsreels and newspapers’ in Angel Quintana and Jordi Pons (eds.), The Construction of News in Early Cinema (2012)

On first sight this seems merely to be a wordier reiteration of the pithy one-liner from 1992. But there are differences, or refinements. I’m now stressing the importance of the producer, and of the day. I was struck particularly by the former while going down an escalator at St Pancras railway station and seeing an electronic screen delivering news headlines. Something about it bothered me, then I realised what it was. It didn’t tell me who had produced these headlines. There was no credited author, no means for me to judge the trustworthiness or bias of the body delivering such news. I felt disoriented – even offended. I may baulk at the blatant bias of some news providers, but at least I know where they are coming from and can adjust my understanding accordingly. Here I felt that, without that identifiable producer, it wasn’t news.

Also important is that notion of the day. My interest in news has always been not just its history but in how it can be listed and discovered. I have managed a database of newsreels in my time, and in doing so thought a lot about how you could connect different newsreels together by what was issued on a particular day, so that you would get a larger picture of what the news agenda was. News cannot be held by one medium. Here’s what I wrote about this in another recent essay:

Consider how one reads the news today. One may hear the radio news in the morning, or catch breakfast television. A journey into work might mean a newspaper, to be read in a variety of ways according to time available or personal interest – one can, of course, read a newspaper and consciously avoid anything that might be described as ‘news’. Gradually one pulls together a composite picture of what one wants the news to be, seeking out confirmation through headlines, web pages, RSS feeds, mobile phones and podcasts, according to one’s degree of media literacy. We make the news what we want it to be.

‘Newsreels: Form and Function’ in Richard Howells and Robert W. Matson (eds.), Using Visual Evidence (2009)

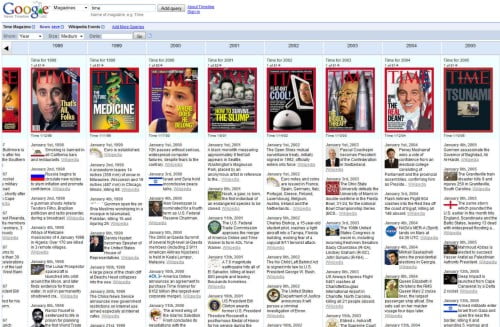

News is a composite. It does not lie in any one newspaper, television news programme or cinema newsreel. It lies in our heads. An interesting question is whether this has always been so or whether it is a particular condition of modern living (this is a major topic to which I’ll return in a later post). But the challenge as I see it is how to bring these different news media together in database form, so that the its structure echoes how we find the news. Google Labs had an excellent tool, News Timeline, which demonstrated this. It allowed you to select news stories from different digital journals and websites across a day, week, month or year, letting you select your own news not just according to the subject you chose but the news media through which you chose to view it. Sadly the service is no longer available, though one hears rumours of its return in some form.

But the database should have more that that. It should tell us from whom the news came and to whom it was delivered, not just when it was delivered. What was news to one person was not necessarily news to another. What is news only locally can suddenly become news globally if it has wider implications (i.e. if it can interest a wider audience as news). I would like to see a database that could identify for me, say, all of the news outlets owed by News International (paper, web, broadcast), the territories to which they were directed, and how the audience for such news outlets might have grown (or shrunk) over time.

Some of this Broadcast News tries to do. We capture news broadcasts from several channels, among them BBC, Bloomberg, CNN, Al-Jazeera English, Russia Today, NHK World and China’s CCTV News. It is news from many global sources, but it is all directed at British audiences because they have chosen to have such broadcasts available free-to-air in the UK through Freeview and Freesat. It is available to us in the UK, it can have an impact on the UK’s view of the news. It is all searchable by day, of course, so that I can see what the headlines were at any one time and make my choice as to what I want to study about the news, knowing its source, its period, its audience, and its relationships with other news broadcasts.

It is easy to see how the model could expand to incorporate other news media. Not all news is published daily, of course, so one needs to allow for the weekly and the monthly (and maybe, in the other direction, the hourly). And then you could do more exciting things with such a data model, by incorporating other artefacts that are not ‘news’ of themselves but could be connected to a news database to given a wider sense of what happened, or what connects to what happened. Why not add in the books that were being read at that time, or the music that was being listened to, by including book and music chart data? Or add tweets, blogs, diaries, photographs? If everything in a library is dateable, might it all be considered, one way or another, as news?

Is the whole of the British Library a news library?