Kinemacolor was the world’s first successful natural colour motion picture system. It was preceded by some trial colour systems that did not work in practice, and it competed against artificial systems which painted colours onto film stock. Kinemacolor was the first system successfully to achieve one of the primary goals of the pioneers of motion pictures, which was to capture and reproduce the world in colour. From 1908 and for around seven or eight years, it was triumphant, presenting what was for many the best that the motion picture medium could achieve, and changing public perceptions of that medium along the way. It features in most histories of the medium, as an important milestone in cinema’s development.

Yet for the past one hundred years hardly anyone has seen it.

Close to a thousand Kinemacolor films were made between 1908 and 1917, but when the parent company of Kinemacolor’s founder Charles Urban went bust in 1924, the greater part of the Kinemacolor library was lost, most likely destroyed when it no longer had any commercial value. Kinemacolor worked by using a rotating filter with red and green sections (or variations on those colours), on camera and projector, producing a restricted but credible colour palette. Because it could only be shown on specialised projectors, and was more expensive to operate than standard film (alternating red/green records meant that it used up twice as much film), for most looking after it was more trouble than it was worth. And so it was that Kinemacolor disappeared from history.

Kinemacolor was not entirely lost, however. Some test films made by its inventor, George Albert Smith, were preserved by a neighbour of his, Graham Head, which ended up at the BFI National Archive and the Cinema Museum. Though limited in scope, these half-dozen short films – among them Cat Studies, Pageant of New Romney, Hythe and Sandwich and Two Clowns – have given us some idea of how Kinemacolor looked. In America, one reel of a 1913 three-reel drama made by the Kinemacolor Company of America, The Scarlet Letter, was held by George Eastman House, and some odd fragments including beachside scenes taken at Atlantic City, a fragment showing actress Lilian Russell from a film entitled How to Live 100 Years (1913), and a few others such snippets were held by the Library of Congress and some commercial footage libraries. One or two archives in Europe had isolated examples of Kinemacolor actualities. But the survival rate for such an important part of cinema history was wretched, and Kinemacolor remained more written about than seen.

Then in 1992 came news of a substantial collection of Kinemacolor films, acquired from a private collector by the Archivio Cinematografico Ansaldo in Genoa. Passed on to the Cineteca Bologna, the twenty or so films presented a major preservation challenge for the city renowned film lab, L’immagine Ritrovata, with many in an advanced state of decay. One film from the collection, Nubia, Wadi Halfa and the Second Cataract (UK 1911), a captivating travelogue, was made available, showing Kinemacolor in all of its haunting beauty, but the rest remained to be puzzled over in the labs.

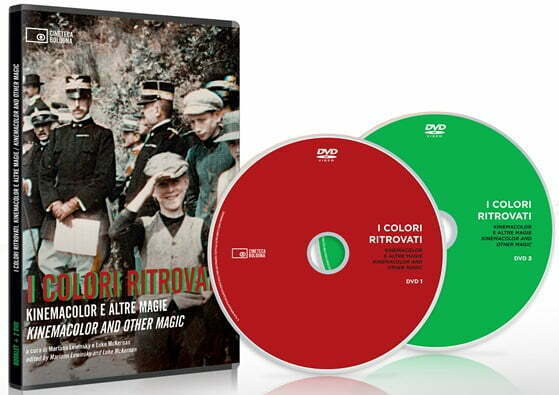

At the 2017 Il Cinema Ritrovato, the festival of archive and restored films held annually in Bologna, Kinemacolor was reborn. A ninety-minute programme of Kinemacolor films was shown, comprising films from the Cineteca Bologna, the BFI, EYE (Amsterdam) and the John E. Allen Archives in the USA. More than that, the Cineteca Bologna has released a two-DVD set, Kinemacolor and Other Magic, co-curated by Marian Lewinsky and my humble self: the first disc Kinemacolor productions, the second disc has artificial colour films made by Pathé from the same pre-WWI period, and three-colour films of surpassing beauty from Gaumont Chronochrome (circa 1912-13 and technically Kinemacolor’s superior, but they received little distribution at the time) for comparison. Suddenly we have riches.

So, what is available for us to discover? On the DVD there are fourteen Kinemacolor films. Two are from the test films made by G.A. Smith and held by the BFI: (Woman Draped in Patterned Handkerchiefs) and (Tartans of Scottish Clans). The first shows Smith’s daughter Dorothy draped in tartan patterns, turning around to show the colour effect; the second features the same cloths in close-up. They are likely to date from late 1907 (a demonstration of Kinemacolor as a work-in-progress was given to film trade representatives in November 1907).

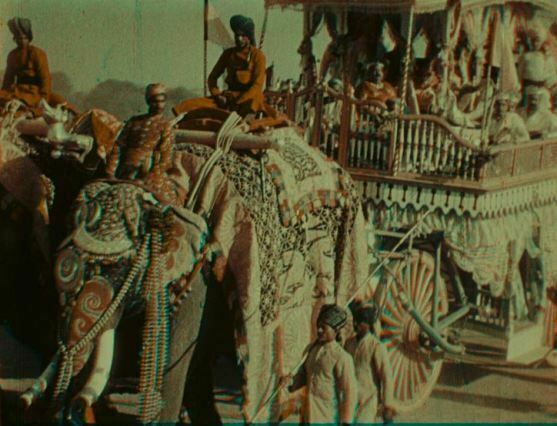

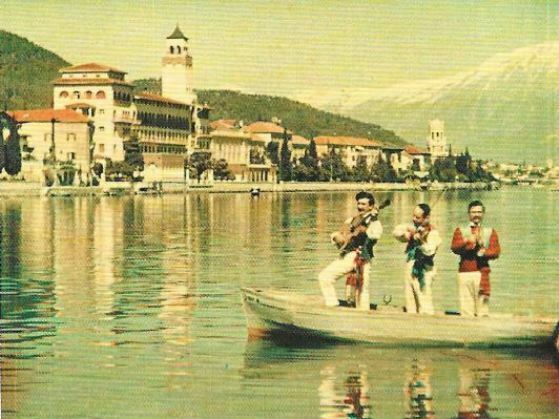

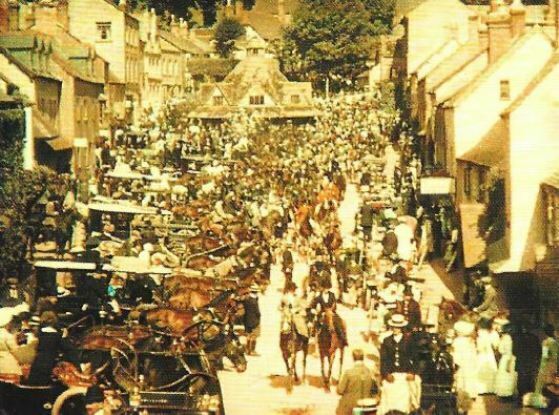

Then we get the Bologna films. Eight of these are one-reel actualities made by Kinemacolor’s parent British company, the Natural Color Kinematograph Company. They are The Harvest (1908), Fording the River (1910), Lake Garda, Italy (1910), Feeding Poultry at Prowse Jones Farm (1911), A Run with the Exmoor Staghounds (1911), Coronation Drill at Reedham Orphanage (1911) (this title is actually from EYE), Nubia, Wadi Halfa and the Second Cataract (1911), and – most sensationally for colour film history – a reel from Charles Urban’s famous two-and-a-half hour record of the 1911 Delhi Durbar, With our King and Queen Through India (1912). The section is entitled The Pageant Procession, and shows a parade of elephants with howdahs held at Calcutta shortly after the main Durbar ceremony.

The films are all fascinating for their muted, otherworldly colour and notable for their studied artistry. Two are outstanding. Lake Garda, Italy (1910) is an immaculately composed travelogue, with expert shot selection and composition combined with lyrical water effects (one thing one learns from the DVD is how good Kinemacolor was at recording water). The subject matter of A Run with the Exmoor Staghounds (1911) is horrendous (the killed stag is seen at the end of the film), but the narrative technique is impressive, with multiple shots taken as eye-catching angles, the filmmakers being careful to feature action coming towards the camera rather than laterally (lateral motion in Kinemacolor films is affected by colour fringing, because of the imperfectly aligned red and green records). One breathtaking high-angle shot alone, of the hunt passing through the village of Dunster in Somerset, is a classic production in itself.

There are also four films on the disc made by the Italian Comerio company. How Comerio came to have a Kinemacolor camera, when the process was so tightly controlled, remains a mystery at present, but probably it was some sort of sub-contractual arrangement rather than piracy. The films, of troops in Libya, cavalry crossing a river, a news event in Venice, and fountain, are of variable quality technically, but the colour is excellent. Watching the full programme, one becomes lost in this other world, where the colour is somewhat drained, yet fully realised within the constraints of that world. Colour films from the distant past (in motion picture terms) tend to have a surprise quality of making that past strikingly present, as the captured reality hits us. Kinemacolor, because the colour reproduction is imperfect, does not have quite the same effect. The past remains past, out of reach, still wrapped in the mystery of the passing of time.

There is more to come. At a panel given on the films at the festival, we learned that around a third of the Bologna films have now been restored and published on disc, a third are probably it too great a state of deterioration for anything to be recovered from them, and a third are being worked on, to be made available in due course.

And there is more elsewhere. Two films shown at Bologna but not on the disc came from the John E. Allen Archives in America. One was a two-minute extract from Balkan War Scenes, a set of Kinemacolor films made by the renowned war journalist and illustrator Frederic Villiers, with camera operator James Scott Brown, to accompany lectures given by Villiers on the 1912 Balkan War. What survives is fragmentary, but features Greek cavalry, navy and troop manoeuvres.

The second film was a sequence from Britain Prepared (1915), a prestigious documentary feature film about the British army and navy made by Urban for the covert British propaganda outfit, the War Propaganda Bureau. The greater part of this two-and-a-half hour film was shot in monochrome, and is held at the Imperial War Museums. But a third of it, showing the Navy at Scapa Flow, was filmed in Kinemacolor. A precious two minutes survives, showing battleships at sea firing their guns, the only colour film known to exist of the First World War.

There are other Kinemacolor films in the Allen archives yet to be identified. identified in its records as ‘flicker’ films, they were stored for a long time as curiosities whose action was in slow motion when shown at standard projection speed, and which flickered oddly. This is because Kinemacolor films appear to be black-and-white. They were filmed through a rotating red/green filter wheel, and projected the same way. In projection the alternating red and green records were brought together at double-speed (around 30 frames per second). Shown through an ordinary projector, you get a film shown at half its correct speed, and with flickering black-and-white which is actually a reflection of those alternating tonal records.

These shots from the British Pathé archive are hidden Kinemacolor (betrayed by the half-speed and distinctive flicker). They are unidentified films dating around 1910-1913 from both British and American Kinemacolor (the Atlantic City scenes exist in other archives as well)

Other film archives and footage libraries have these peculiar monochrome films that run slowly and flicker oddly. There needs to be an international call to track them down, so that we can find more Kinemacolor. Of the thousand or so Kinemacolor films that were made, around fifty survive that we know of. But it must be possible to do better than that.

Because Kinemacolor film do turn up. The most famous example was in 2000, when TV producer Adrian Wood, working on a television series The British Empire in Colour, found a reel of With Our King and Queen Through India at the Russian film archives in Krasnogorsk, labelled as First World War troop movements, when what it actually showed was a parade of the British army after the main Delhi Durbar ceremonies. At the Bologna show, the British Film Institute announced the happy news that it had recently found two Kinemacolor films (on eBay!). The films, or at least some of them, are out there, if we just look.

These Kinemacolor discoveries should change film history, at least in a small way. Much has been written about early colour systems, but almost entirely about Pathé stencil colour films, which are pretty to look at and easy to find. We now have a body of work in Kinemacolor which is representative of the best that the system had to offer, and which will rebalance studies made into the aesthetics of early cinema.

But more than that, we have lost treasure rediscovered. The great allure of Kinemacolor has been its elusiveness as much as the allure gained from the high praise it received in its day. A little of the elusiveness has been removed, but the vast majority remains lost and never to be recovered. We can look on what we have and marvel at it, because there is enough there of great quality to make us rue the loss.

Here are some examples of the lost Kinemacolor films, whose re-discovery would be a particular cause for celebration:

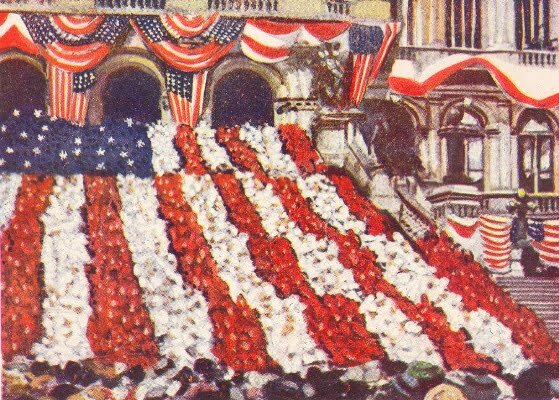

- Children Forming the U.S. Flag (1909) – the first Kinemacolor film made in America

- Constantinople and the Bosphorus (1909?) – among the particularly enticing travelogues made in Kinemacolor

- By Order of Napoleon (1910) – the first Kinemacolor fiction film

- The Unveiling of the Queen Victoria Memorial (1911) – the film that established Kinemacolor’s special connection with pageantry and royalty

- The Making of the Panama Canal (1912) – Kinemacolor’s leading prestige long film after the Durbar coverage

- The Clansman (1912) – unreleased predecessor to D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation

- The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1914) – the first Kinemacolor fiction feature film

- Sack of Louvain by the Germans (1914) – the First World War in colour

Links:

- Kinemacolor and Other Magic / Kinemacolor e altre magie is available from the Cineteca Bologna (currently it is listed on the festival site but not yet listed on its Cinestore online shop [Update, Sep 2017: it is now available]. The two DVDs, wittily coloured red and green in tribute to Kinemacolor filters, come with extras including a documentary on restoring colour, images from the 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue, and a 72-page booklet (in Italian and English)

- There is a listing of all known surviving Kinemacolor films on my Charles Urban website

- Colour images of Kinemacolor films, as produced by an artist for the 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue, can be found on my Flickr site and were the subject of an earlier blog post

- Catalogue entries for the Kinemacolor films shown at the 2017 Il Cinema Ritrovato are on the festival website

- A programme of Kinemacolor films as featured at Bologna will be screened at the Watershed, Bristol, on 30 July – more details here

Dear Luke,

Thanks for your interesting text. May I kindly suggest that you add the Timeline of Historical Film Colors to your list of links? Thanks!

You may find the history of additive processes based on temporal synthesis here:

http://zauberklang.ch/filmcolors/cat/rotary-filters/

Best regards,

Barbara Flueckiger

Prof. Dr. Barbara Flueckiger

Department of Film Studies

University of Zurich

http://www.film.uzh.ch/team/people/flueckiger.html

ERC Advanced Grant FilmColors: http://filmcolors.org/2015/06/15/erc/

Timeline of Historical Film Colors: http://zauberklang.ch/filmcolors/

Research project DIASTOR: http://diastor.ch/

Dear Luke,

thanks for this article. I am also interested in color film.. before color film became the norm. I did some research on kinemacolor in Belgium.. and published it in magazine of the Museum MIAT in Gent. Convents (G.). De Belle Epoque in kleur. Kinemacolor : op- en ondergang van de eerste kleurenfilms in België 1911-1913, in Tijdschrift voor Industriële Cultuur, 2002, nr. 3, speciaal nummer

I hope next year to go deeper into this research about the how and the what about kinemacolor and color film in Belgium before the First World War. So thanks again for you publication ..see you soon – somewhere !

Hi Guido,

I cite your article in my Charles Urban book. It really would be good to know more about Kinemacolor in Belgium, particularly what was filmed there at the start of the war. I’ve named one of the films, Sack of Louvain by the Germans, in my list above of lost Kinemacolor films that it would be particularly good to see again.

See you soon somewhere, indeed.

Luke

I am going to be giving the Ernest Lindgren Memorial Lecture at the London Film Festival, on 11 October 2017. The subject will be Kinemacolor, with lots of restored films to show. Details here: https://t.co/7fV5W6HPxu

I have uploaded the text of my Ernest Lindgren Memorial lecture on Kinemacolor, with thumbnails of all the images used and screengrabs from the films shown:

https://lukemckernan.com/wp-content/uploads/Kinemacolor_Lindgren_lecture.pdf

The 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue is now available on the Internet Archive, c/o McGill University Library, Canada https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-rbsc_catalogue-kinemacolor_ColgateIXNaturalColor-17612/page/n19