I’ve been adding more images to my Flickr pages reflecting the works of Charles Urban. Having started with pictures from his 1903 catalogue We put the World Before You, I’ve turned to another treasure among his catalogues, the Catalogue of Kinemacolor Film Subjects (1912). Copies of this catalogue are rarer than hen’s teeth, and I’m the proud owner of one. It’s a catalogue of most of the film productions made by the Natural Color Kinematograph Company, a British film company which Urban set up in 1909 to make films using the Kinemacolor process (different Kinemacolor companies made films in other countries as well).

Kinemacolor was the invention of George Albert Smith, a Brighton-based performer, filmmaker and film processor, who patented a system for filming in natural colours in 1906. The history behind the invention of Kinemacolor is a complicated one. Essentially there was much interest and competition among some filmmakers in Britain in the early years of film to develop a natural colour film system (as opposed to applying colour to films by hand or using stencils). Several of these rivals in colour – among them Benjamin Jumeaux, William Norman Lascelles Davidson, Otto Pfenninger and William Friese Greene – were based in the Brighton and Hove area, and were each linked with Smith as an expert film processor.

Urban stepped in when an inventor of a putative three-colour process (i.e. using a red, green and blue filter to create a colour effect), called Edward Turner, whom Urban had been supporting financially, fell dead in 1903. Turner’s system did not work in practice, and Urban turned to Smith to develop Turner’s invention to a working model. Smith discovered that if he removed the blue filter, the remaining red and green could given a reasonably good colour effect, with a lot less wear and tear on the film (which went through the projector at 30 frames a second instead of the 48 fps expected by Turner). He achieved success in 1906.

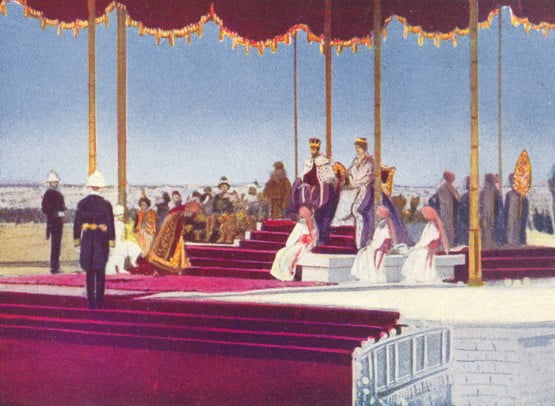

The story of Kinemacolor I’ve told elsewhere. It was launched to the film trade by Charles Urban in May 1908, made its public debit under the name Kinemacolor in February 1909, and for five years it became the sensation of the cinema world: for its conquest of colour (it was the first successful natural colour film system); for its spectacular non-fiction films, often trading on fascination with British royalty; and for the classy audiences that it attracted, to theatres rather than cinemas, who happily paid high prices, which seemed to promise a wealthier, more culturally elevated kind of cinema.

It all fell apart in 1914 after a court case brought about by William Friese Greene, inventor of a massively inferior rival colour system, Biocolour, which nevertheless led to to revocation of the Kinemacolor patent. Some Kinemacolor films were made in 1915, including scenes of the British war fleet at sea for a propaganda feature filmm entitled Britain Prepared, and as late as 1917 Kinemacolor was being used for film production in Japan, but essentially the court case killed the business. Other colour system that were chemically rather than mechanically based, then took over, most notably Technicolor.

The 1912 catalogue is an emphatic document of Kinemacolor’s great years, from the first efforts in 1908, through to the triumphant recording of the Delhi Durbar ceremonies in 1911 which marked the coronation of King George V, acknowledging him as Emperor of India. Kinemacolor expressed the imperial certainties of its age, and the catalogue is a portrait of that world, reflected on the screen as never before. It is mostly non-fiction films, because Kinemacolor worked best in natural light, and though there were Kinemacolor fiction films made, few if any were distinguished.

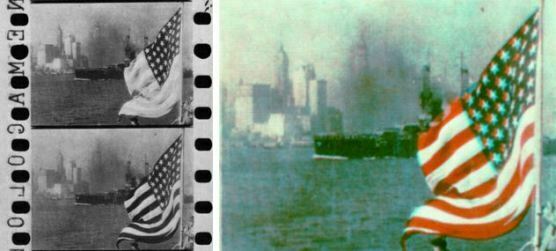

The magical thing about Kinemacolor is that the colour only appeared in projection. Pick up a strip of Kinemacolor film, and it appears to be ordinary black-and-white stock. It’s only when you look closely that you see a slight tonal difference between adjoining frames. That’s because every pair of frames shows the same image, shot once through a red filter and and once through green filter. Only when the film was projected through a rotating filter green with red-green portions, did the colour effect magically appear.

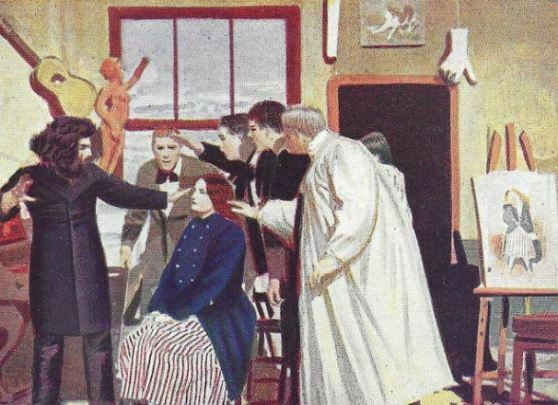

This was a problem for a catalogue of Kinemacolor films, because there was no way to reproduce the colour photography. It was a mechanical impossibility. So, instead, Urban got an unnamed artist (or maybe artists) to paint colour approximations, working from frames of the films, and quite probably with reference to these films as they were projected. There’s evidence for this in the reproductions of images from the fiction films – British Kinemacolor fiction films were made in an open-air studio because of the need for sunlight (Kinemacolor absorbed too much light to work in a conventional studio), and the images show the sharp lighting, as well as the strong shadows, which the artist could only have made if they had seen the films projected. And so the 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue is filled with colour images that purport to be Kinemacolor, yet are no such thing. But they suggest something, and so we can dream.

It is necessary to dream, because so many of these films are lost. Of the 64 images in the catalogue, only 6 represent extant films (and there are some 270 films in the catalogue overall). For the rest, we can only imagine how these stills might have burst into life, and with what colours. There is something unique about them, because not only are they images of lost films (there are plenty more of those), but the way of seeing them is lost too. They lie twice over – suggesting that the films might be seen, and how they would appear. The extra leap of the imagination required only enriches the appeal, however. There’s a part of us that needs things to be lost. The recovery of what is past can only ever be incomplete, and if we have the artefact we still lack, or can only guess at, the signification it held in its original time and place. So we keep on looking, and never quite finding, because time has passed. But realising that time passes is what makes us human. In knowing what is lost, we better understand ourselves.

Links:

- The Kinemacolor images are on the Charles Urban album on my Flickr site – if you want to go straight to the Kinemacolor images, they are here

- There’s an overview of Kinemacolor on my Charles Urban website

- I wrote about the invention of Kinemacolor in these two poss on the Bioscope blog – The Brighton School and Inventing Kinemacolor

That is a shame and Kinemacolor was a cool stock!

I think Kinemacolor did 300-500 movies throughout the life of the company.

The 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue is now available on the Internet Archive, c/o McGill University Library, Canada https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-rbsc_catalogue-kinemacolor_ColgateIXNaturalColor-17612/page/n19