Last weekend I sat through six hours and thirty-seven minutes of of Les Misérables (France 1925), the longest film I’ve ever experienced at a single sitting. It was shown at the Barbican in London, two comfort breaks and a supper break along the way. Neil Brand provided the live piano score, as he had with this film’s acclaimed presentation at the Pordenone silent film festival last year, and he was deservedly given a standing ovation at the end of it. It was not just an endurance feat, but a remarkably sustained accompaniment that was sympathetic, inventive, supportive and which never flagged for a single second.

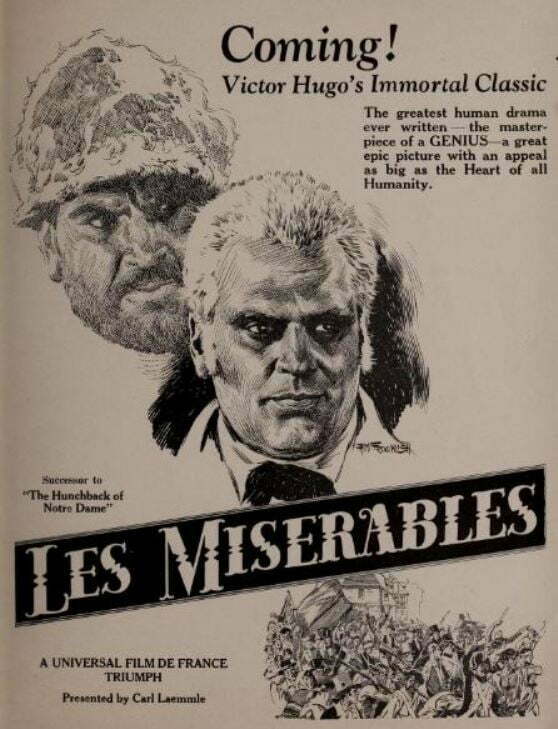

The film itself is a remarkable exercise in sustained invention. Though in 1925 it was soon cut down in size for more a practical release, the film is notable for how it maintains narrative control over nearly seven hours, a model demonstration of pacing, composition and planning by director Henri Frescourt. That said, Les Misérables is not a great film. The ecstatic accounts you may find about the film are understandable, given the epic nature of the experience of viewing it, and the film’s many virtues (the performances, especially Gabriel Gabrio as Jean Valjean and the precocious Andrée Rolane as the young Cosette; the nightmarish forest with trees coming to life to terrify Cosette; the compelling use of settings seemingly unaltered since the 1830s; the hard-bitten faces true to the bitter times the story reflects). And silent film buffs do love to talk up their subject, which is a forgivable vice.

But there were so many blemishes of a kind to puzzle the sceptic and embarrass the advocate. Mismatched shots (particularly in cut from mid- to close shots of characters), continuity howlers (the grille to the sewers near the end was a different grille for inside and outside shots), frequent examples of shaky focussing, and even people in 1920s attire seen walking in the background of the scenes set in the Luxembourg Gardens. Why so much effort in some respects, yet such sloppiness elsewhere? Did they not see what we see?

In particular I was bothered by the dead. I’m always interested in scenes of the dead on screen, because I like to see the actor holding their breath. How long will the director keep that shot going? I wonder each time. In the BBC’s 1976 I Claudius series there’s an extraordinary scene in which Brian Blessed, as the dying and then dead Augustus, is obliged to lie not breathing at all for over four minutes minutes while Siân Phillips, playing his wife Livia, confesses to her crimes (she is the one who has poisoned him). It is a tour de force, it is a memento mori, and no corpse could have done it better.

How very differently Les Misérables treats the dead. When Baron Pontmercy (played by Luc Dartagnan) dies in his bed, and his estranged son Marius arrives just too late to be reconciled with him, the film shows him in quiet repose, his chest noticeably rising and falling. The blemish makes things all the more confusing when Marius himself is severely wounded following the revolt at the barricades, and Valjean carries him through the sewers. Is he dead or isn’t he? When we see his bloodied body and notice his eyes move, is that a sign of hope, or of an actor (François Rozet) who just couldn’t keep still when you needed him too? What were we supposed to believe?

I was brought up on unconvincing deaths. The westerns we saw at Saturday morning cinema shows, the war movies and adventure serials on television, were filled with people who clutched at unbloodied chests when apparently shot, lying there at rest until the director called ‘cut’. We were convinced that those screen deaths were real, or at least I think that we were. We judged them not by how convincing they were but accepted what they signified. Perhaps that excuses Les Misérables, which puts the idea over the actuality and was presumably content with that.

We have moved on, and now expect our screen deaths to be that much more convincing. Bullets must make a mark, swords cut deep, blood must spurt. But that is the killing rather than the death. For that an essential purity of performance remains. All the actor can do is to lie there, not breathing, playing possum. Like the opossum, which is particularly adept at displaying what is technically known as ‘defensive thanatosis’ (playing dead to fool a predator), we have the facility to mimic our demise. For all of the realism of the modern day moving image, which needs to persuade a worldly-wise audience for whom the pretences of Les Misérables or Saturday morning serials would be laughable, the performance of death is something that must always remain same, fundamentally false and symbolic. In that I Claudius scene death is not what you see, you don’t really even see the Emperor Augustus – you just see poor Brian Blessed motionless, trying not to go red or to betray the minutest evidence of an expelling of air. If we didn’t see him breathing, we always knew that he might. It’s not so different from Les Misérables after all.

Perhaps there is a period of time in which we suspend disbelief and experience the sense of the life lost, only for it to be followed by a loss in that belief as the death scene continues. If there is such a moment, it is lost immediately upon its contemplation. The mourners no longer mark a death but are actors in a fiction whose mechanics have been betrayed. It’s just a story. Nobody died after all. You can breathe out now.

Links:

- There are good reviews of the screening of Les Misérables on John Wyver’s Illuminations blog and by Paul Joyce

- Neil Brand writes about the film and his music on the Barbican blog

- Brian Blessed and Siân Phillips discuss the I Claudius Augustus death scene in this programme

Luke:

I think you put your finger on it, in noting that Les Mis is not without ‘blemishes’ – ‘Did they not see what we see?’. Well, no, they clearly didn’t. And what we inevitably miss in modern presentations of this kind (esp Napoleon, of course) is what and how they DID see in the 1920s. This is what we can’t recover, although we can hypothesise; and even try some experimental ‘recreations’ of the early viewing experience. But we belong to a different era, shaped and nourished by different audiovisual experiences (as you note re screen deaths). But of course I agree with all you say about Neil’s heroic performance, which makes it all work today. Aren’t we lucky?!

To be frank I don’t know what point I was trying to make, but agreed entirely about Neil’s superb performance. No better way of helping us discover and recover that past.