The poet was a scientist

The scientist was a poet

The one always saw the world with the eyes of the other

‘In the microscope’, for instance

Here too are cemeteries,

fame and snow.

And I hear murmuring,

the revolt of immense estates.

It is the view of one who understood the puzzle and the paradox

of what it is to observe

or to imagine observation, as in ‘Brief Thoughts on Cats Growing on Trees’

In the days when moles still held their general meetings

and were able to see better, it happened

that they wished to know what existed

above.

And they elected a commission to investigate.

The commission delegated a sharp-sighted, quick-footed

mole. Leaving his bit of mother earth

he sighted a tree and a bird sitting in it

From this the moles determine that birds grow on trees. But a second mole

notes that cats screech in trees

hence screeching cats grow on trees

A third mole goes out at night and concludes

Birds and cats are optical illusions caused by the refraction of light. In reality, above

is the same as below, only the earth is thinner and

the upper roots of a tree whisper something,

but only a little.

Such is understanding

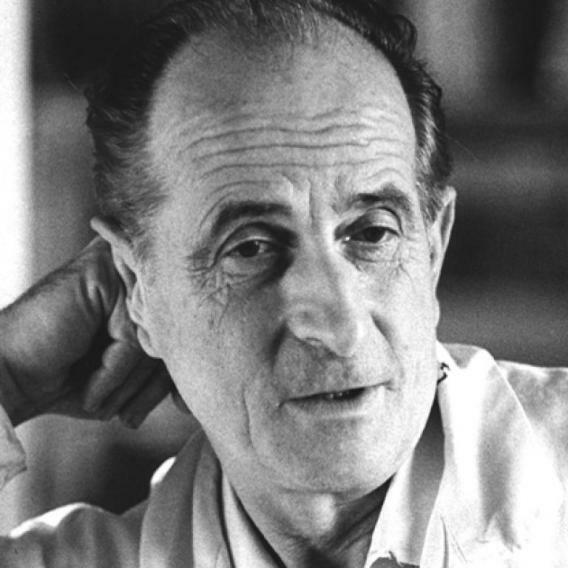

He was a poet, he was a immunologist, both of whom

investigate through

experimentation

He was born in 1923, in Czechoslovakia. He ceased to be born in 1998

Miroslav Holub was the name on the label

The surname is a poem in itself

its two parts each

echoing

the complementary other

His poems are mysterious and clear

Like thought

There are minotaurs and trilobites

Cat and clowns

Prince Hamlet and Cinderella

Angels and gorgons

Arthropods and subway stations

Diseases and puppets

Teeth and ‘Wings’

But above all

we have

the ability

to sort peas,

to cup water in our hands,

to seek

the right screw

under the sofa

for hoursThis

gives us

wings.

The poems are inviting to read, they make the reader

look again

On visiting ‘The British Museum’, for instance

(from which these are extracts, separated by ellipses)

According to the rules of the fugue,

any ark

will be ruined

once, the trilingual

Rosetta Stone will be broken, stelae of Halicarnassus

will turn to dust, sandstone Assyrian spirits

with eagle heads will shyly take off…Only genes are eternal,

from body to body,

from one breed to another breed,

on Southampton Row …So the British Museum is not to be found

in the British Museum.The British Museum is in us,

in our very hearts,

in our very depths.

Appropriately enough, it is poetry that translates well

(or so it would seem)

No rhymes, no demanding metres

Some have wondered whether it is poetry at all

But the poetry is in the chemistry

At any rate, it is easy to read, in that it falls

comfortably on the eye

And it is quite easy to imitate

If superficially so

He looks at past and present, the animate and the inanimate, at

the body and the mind. Hence ‘A Boy’s Head’

In it there is a space-ship

and a project

for doing away with piano lessons.And there is

Noah’s ark,

which shall be first.And there is

an entirely new bird,

an entirely new hare,

an entirely new bumble-bee.There is a river that flows upwards.

The poetry is comical and serious

For such is how we find things, looking through our microscope

as others look through theirs at us

and wonder

It can be oddly beautiful too, as we learn from ‘Love’

Two thousand cigarettes.

A hundred miles

from all to wall.

An eternity and a half of vigils

blanker than snow.Tons of words

old as the tracks

of a platypus in the sand.A hundred books we didn’t write.

A hundred pyramids we didn’t build.Sweepings.

Dust.Bitter

as the beginning of the world.Believe me when I say

it was beautiful.

It is Czech to its bones, the mind we see in

Hašek, Čapek, Hrabal, Menzel, Passer, Forman, Chytilová

The words of a land so much invaded down the centuries

Victim of an ever-repeating folly

This we see in ‘The Fly’,

perhaps his best-known poem

(the fly is feeding on battlefield corpses at Crécy)

She rubbed her legs together

as she sat on a disembowelled horse

meditating

on the immortality of of flies …And thus it was

that she was eaten by a swift

fleeing

from the fires of Estrées

What is a poet and what is science?

Holub wonders continually about his role

As well he might

In ‘Interview with a Poet’ he asks himself

You are a poet? Yes I am.

How do you know?

I have written a poem.

When you wrote the poem, it means you were a poet. But now?

I shall write another poem some day.

They you may again be a poet. But how will you know that it is

really a poem?

It will be just like the last one.It that case it will certainly not be a poem. A poem exists

only once – it cannot be the same again.

I mean it will be just as good.But you cannot mean that. The goodness of a poem exists only once and does not depend on you but on circumstances.

I imagine the circumstances will be the same.

We are all seeking that which is unique and true

and expressible

In that respect, we are all poets

and we are all scientists, experimenters,

turning the microscope on ourselves

Curiously, however, Holub never questions his science

as such

Only his poetry

If that is your opinion, you never were a poet and never will

be. Why then do you think you are a poet?

Well, I really don’t know…

But who are you?

This is the seventh in an occasional series of posts on favourite poets of mine

Links

- Miroslav Holub’s collected English translations are published by Bloodaxe Books as Poems Before & After, with translations by Ian Milner, Jarmila Milner, George Theiner and Ewald Osers

- There is information on Holub, with sample poems, at the Poetry Foundation

- Some of Holub’s non-specialist prose writings on science and other topics are printed (in English) in The Dimension of the Present Moment and Other Essays. It includes the illuminating essay ‘Poetry and Science’