Ten and a bit years ago I contributed for the first time to the venerable Sight and Sound once-every-ten-years poll of the greatest films. The poll has been running since 1952. The top choice of the sixty-three critics who contributed was Ladri di biciclette, or Bicycle Thieves (Italy 1948). From 1962 to 2002 the poll-topper was Citizen Kane (USA 1942); in 2012 it was Vertigo (USA 1958). The films I chose in 2012 were not so much what I thought were the ten greatest films ever made, but rather a history of film, ranging from the very first ‘film’ ever made (arguably), to the first ‘film’ uploaded to YouTube. These were the titles I chose (in strict chronological order):

Roundhay Garden Scene (Louis Augustin Aimé Le Prince, 1888)

Le village de Namo – Panorama pris d’une chaise à porteurs (Gabriel Veyre, 1900)

The Big Swallow (James Williamson, 1901)

L’aveugle de Jérusalem (Louis Feuillade, 1909)

The Battle of the Somme (J.B. McDowell, Geoffrey Malins, 1916)

The Lady of the Dugout (W.S. Van Dyke, 1918)

Spare Time (Humphrey Jennings, 1939)

Free Radicals (Len Lye, 1958)

Topsy-Turvy (Mike Leigh, 1999)

Me at the Zoo (Yakov Lapitsky, 2005)

You can read more about each title and why I picked them, on my old silent film website, The Bioscope. However, I used the occasion to stop publishing on the Bioscope, despite its popularity, because I wanted to devote my online energies to a different set of topics. This website was one of the results.

Ten years on and the poll came round again, at the end of 2022. With votes submitted from 1,639 critics, programmers, curators, archivists and academics, it caused quite a stir for its number one choice, Chantal Akerman’s feminist anti-epic Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), not least because so few people appear to have seen it, or indeed heard of it.

The list of 250 titles chosen is an entertaining one, in which you can see a sliding down the poll of the warhorses of old, and new warhorses sliding upwards. The decision almost to double the number of people contributing to the poll has brought about some freshness, not least in the increase in films directed by women, but without shaking the essential absurdity of deciding what is great, and why being great is important. A poll to decide what are the 250 greatest art works (ooh look, ‘The Night Watch’ has just edged out ‘Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995’) would be ridiculous, no less than would be a list of the greatest novels (Moby Dick is the heaviest of the contenders, let’s give it the prize). Films, and pop songs, lend themselves more to such listing, maybe because they are relatively new art forms, still trying to prove themselves. Such lists are great for arguments, and as suggestions for viewing (or listening), but that’s probably all. Were these media taken in full seriousness by all, there might be no need for such polls.

I don’t know what a great film is, and I didn’t try to select ten on that basis. Instead I picked ten films that for me said something about how films work. There was one survivor from my 2012 list; the others I picked for being more conventional feature films this time around. There was no struggle involved in choosing them – they were practically the first ten films I thought of. I wrote this comment on the selection process:

The films I have chosen are not obviously ‘great’, but they exemplify for me what is great about film itself. Each one shows supremely well that our realities are dreamworlds. On any other day I could have picked a different ten that might have served just as well, but these ten each please me for their originality, their modesty, and their visual understanding.

The ten are given below. All but one I have written about before now, and I have supplied extracts from those texts with links (most of which are from this site). The one film I have yet to write about Robinson Crusoe (1954), I will cover in a future post, hopefully soon [Update: I have now written this – see https://lukemckernan.com/2023/05/18/robinson-crusoe]. As not all of the titles are familiar to most, I have also supplied links on where to find them if they can be found. One of them (Open All Night) is not available commercially; another (Atlantic Rhapsody) was on DVD but appears now to be unavailable.

The films are in chronological order.

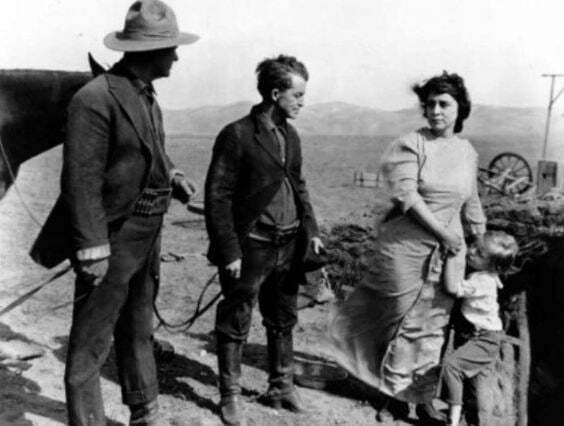

The Lady of the Dugout (USA 1918 d. W.S. Van Dyke)

A reformed outlaw brings about forgiveness.

The story is engrossing, and the insight it gives into a frontier life where dreams have turned sour is a special one. There is an authenticity in locale, in the weatherbeaten looks of the Jennings brothers, in the action (a particularly convincing, almost matter-of-fact bank robbery), in manner and in human feeling. The film develops not out of the demands of story but out of circumstance, character and a true moral sense. The director was W.S. Van Dyke, and I can’t think of a better-handled silent film. It’s low-key, it doesn’t touch on any grand themes (though forgiveness, which is what it is ultimately about, is a noble theme), but it is about things that matter and people that we care for. You feel that nothing stood in the way of the filmmakers being able to tell the story exactly in the way that they wanted to (its sympathetic view of the outlaw life is extraordinary). It’s hard to believe that a film of such easy naturalism was made only four years after The Birth of a Nation.

Source of quote: https://thebioscope.net/2011/10/22/pordenone-diary-2011-day-four

Availability (DVD): Part of National Film Preservation Foundation’s 3-disc set Treasures 5: The West, 1898-1938

Open All Night (UK 1934 d. George Pearson)

In a London hotel, the old must give way to the young.

Open All Night is profoundly a film about itself. Its hapless young protagonists, inexpert in life, still finding their way in their profession, cannot find their way out of the hotel. They sit alone at tables, drinking champagne they cannot afford, as the indifferent crowd passes by. They need Anton, they need George, to steer them to the freedom their youth merits, even though it is he who must pay the price for this. All films are about time. They cut up its flow and explore the effects of this distortion on humans. Open All Night establishes its particular dictate by taking place in near real-time, with no flashbacks and arguably no parallel action. The clock is ticking, just as it does for Pearson and his crew to make the film in twelve days at so many thousand feet and no more (Open All Night was filmed in July 1934, cut in August, released in October, its running time 62 minutes). The film will be shown in a cinema, cheap fodder to fill out an hour in the programme, an entertainment constrained by time, whose special appeal to the audience is that it may eliminate time entirely, or at least conquer it for a while. Open All Night is a tragedy to pass the time.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2021/04/29/open-all-night

Availability: Not commercially available, but has been broadcast on the Talking Pictures TV channel in the UK

Robinson Crusoe (Mexico 1954 d. Luis Buñuel)

A shipwrecked man rebuilds the world as he understands it.

Luis Buñuel’s version of Robinson Crusoe, produced during his Mexican exile period, is fascinating for being barely Buñuelian at all. Despite some claims that the film is an anti-imperial satire, and despite some fleeting surreal elements, the passages that seem closest to Buñuel’s imagination – such as Crusoe and Friday’s debate about God and the Devil – come direct from the pages of Daniel Defoe. In truth this is a film that proves the story defeats all arguments to subvert it, and that is the key to why the film works so well. It is pure myth, perhaps as Defoe had intended, shorn of the economic details in which the author took pride and which have engrossed literary critics, but which offer little to the reader. What is needed, and what we get, is the story a man who recreates the world, because it is imprinted within him to do so. Of course it is a metaphor for the fantasy of western superiority, but it is also the story of anyone left to fend for themselves. To survive they must draw on what they are. The colour is poor, the style plain, but the film is hypnotic. It is everyone’s dream.

Availability (DVD): Amazon.co.uk

La noire de… (Black Girl) (France/Senegal 1966 d. Ousmane Sembene)

Trapped in France, a Senegalese maid fights for her identity

It tells of a Senegalese girl, Diouana. who is employed by a French middle class couple as a maid and nanny, initially in Senegal and then in France, where her sense of entrapment drives her into silence and then to a final act of despairing rebellion. The film’s most haunting moments come at the end, when the Frenchman returns to Senegal to apologise to Diouana’s mother, only to be pursued out of town by a small boy bearing an African mask which has featured as a motif through the film. The film is about the emergence of Africa from out of colonialism and how self-understanding will bring about a return of power. In film study terms, it is about the transference from the colonial gaze to an African gaze. Yet there is no pretension about the film at all. It says very simply what needs to be said, though images composed with great technical ability and political understanding. That it was the first film Sembène had made, indeed one of the very first African features of the modern era, is extraordinary.

Source: https://lukemckernan.com/2015/07/04/in-bologna

Availability (Blu-Ray): British Film Institute

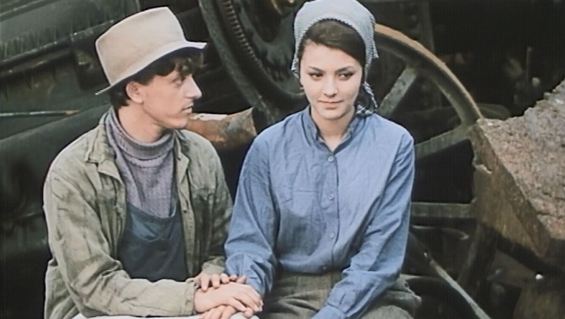

Skřivánci na niti (Larks on a String) (Czechoslovakia 1969 d. Jiří Menzel)

In a scrapyard, dissidents philosophise and find hope in the darkness.

Though set against the bleakest of circumstances in the most unpromising of settings, this is a lyrical and uplifting film, filled with humour both sad and mischievous. It is beautifully shot – cinematographer Jaromír Šofr conjured up shots of exquisite colour amid the piles of rusting metal in the scrapyard, of which the grimy dissidents seemed almost to be an organic part. Amid the absurdities of ideology (a group of children is taken to see the dissidents, their earnest teacher pointing out the sad and kindly women as having “repugnant, imperialism soaked faces”), the men ponder philosophical questions, keeping understanding alive. In every scene, the prison in which they find themselves is undermined by minds that question and hearts that beat true.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2020/09/08/jiri-menzels-closing-shot

Availability (DVD): Second Run DVD

Ko To Tamo Peva (Who’s That Singing Over There?) (Yugoslavia 1980 d. Slobodan Sijan)

A motley group on a bus to Belgrade face up to random disasters.

Who’s That Singing Over There? is an an excellently crafted gem with a bleak sense of humour. It tells of a group of people travelling on a bus to Belgrade on 5 April 1941 (the day before the German invasion of Yugoslavia), and the various disasters that befall them along the way. It might have been played simply as broad comedy with national types to appeal to a Serbian audience alone, but its bleak undertones and distinctive setting in the flatlands of Yugoslavia make it something universal, and exceptional. The sort of insight into history and society that only film can provide.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2016/02/17/forgotten-films-of-the-1980s

Availability (DVD): Balkan Media

Every Picture Tells a Story (UK 1984 d. James Scott)

A child looks around him and becomes an artist.

The narrative is irrelevant, however. What matters is what is seen, and felt. There are the saucepans, plates, pots and tables that most obviously recur in William Scott’s later art, which is revealed by the startling cuts from figurative memory to abstract expression as the film cuts from story to paintings. There is the collapsing of time, between the unfolding story and the figure of William Scott himself, heard speaking but filmed sitting wordlessly, and between past and present most ingeniously (and economically) where Scott’s father prepares to go on an Orange parade in the 1920s before we see a 1980s parade taking place outside. Nothing, incidentally, is made of politics or religion, in the film. It is simply a part of the picture, of what is seen and felt. The pictures spring out of the story of William Scott, and they have no story at all. All that is there is all that you can see.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2014/02/07/every-picture-tells-a-story

Availability (DVD): British Film Institute

Atlantic Rhapsody – 52 myndir úr Tórshavn (Faroe Islands 1989 d. Katrin Ottarsdóttir)

Over twenty-four hours a society tells its interconnected stories.

Its subtitle translates as ‘fifty-two pictures from Tórshavn’, and it depicts twenty-four hours in the life of the Faroes through fifty-two interlocking narratives, so that as one mini-story ends a character or incident from it spills over into the next story, and so on chronologically until it builds a remarkably effective picture of time, place and people. I was greatly impressed by its ingenuity and technical skill, including excellent performances by Tórshavn inhabitants. A wholly original piece of work, which was the first Faorese-produced feature film ever made. A pleasure to watch for its filmmaking skill, its geographical and sociological interest, and to see how the worst of 1980s fashions even made it to the Faroe Islands.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2016/02/17/forgotten-films-of-the-1980s

Availability (DVD): Blue Bird Film (currently listed as Out of Stock)

La camarista (The Chambermaid) (Mexico 2018 d. Lila Aviles)

A chambermaid has her small dreams but finds only disappointment.

It is a quiet, acutely observant piece that never put a foot wrong. It tells of a chambermaid (played by Gabriela Cartol), working in an exclusive hotel, who is the model professional but seeks to better herself in the face of great hurdles, including long hours, an arduous journey to work, and caring for her child. It is a tragedy without melodrama. Its victim is trapped (by class, place, upbringing, gender, expectations), with the slight signs of hope the film seems to be leading us towards being overturned by the inevitability of a fate determined by society. Beautifully composed, meticulously observed, achieving such visual delight from mere bedsheets alone, I thought it rather better than last year’s not dissimilar Roma, which reached the heights but also had its questionable moments. The Chambermaid does not.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2019/12/19/2019-the-year-in-film

Availability (DVD and download): New Wave Films

The Last Black Man in San Francisco (USA 2019 d. Joe Talbot)

A young man reclaims a romantic building as his true home.

It is an ingeniously directed tone poem of sorts, set in San Francisco, with the metaphorical story of two friends reclaiming a vintage house that one of them (Jimmie Fails, playing Jimmie Fails, a haunting performance based to some degree on his own life) believes was built by his grandfather. The friendship between the two was so well-drawn, likewise the broader picture of a black society trapped in boxes. It fell apart somewhat towards the end, when Fails’ writer friend Mont Allen (wistfully played by Jonathan Majors) puts on a play which is a rant that doesn’t work, but Hamlet has a weak play-within-a-play and is still Hamlet. A remarkable film, memorable for its precise depiction of male friendship, and some dazzling visual coups by director Talbot.

Source of quote: https://lukemckernan.com/2019/12/19/2019-the-year-in-film

Availability (DVD and Blu-Ray): Amazon.co.uk

Links

- The 2022 Sight & Sound poll is here: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/greatest-films-all-time

- The list of all those who voted, and what they voted for, is here: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/greatest-films-all-time/all-voters (each individual film has a link to all those who voted for it)

- My selection is here (the job title given is no longer valid – I retired a short while after submitting my selection): https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/greatest-films-all-time/all-voters/luke-mckernan

Thanks for this most entertaining post Luke. I can’t explain why, but moth-like, I’m drawn to the flame of lists like these, but I’m probably looking for points of agreement or familiarity as much as for illumination.

Whilst there are no such common points in your list (because I don’t know any of the films you have chosen) it was nevertheless a joy to read and some inclusions were a touchstone for me to a glorious period when exposure to world cinema was reasonably easily achieved via the auspices of a then nascent BBC2 in a time of fewer choices.

Such lists are subject to change the next day or even the next hour of course – a trope trotted out in every episode of Desert Island Discs – but that’s not their point I think; rather they act as lights along the way in the writer’s general direction of travel where different lamps would serve the purpose just as well.

I’m very much drawn to such lists too, and I like producing my own, so the stuff I wrote about the meaninglessness of such lists is a bit hypocritical. Films just lend themselves to categorisation and polling. And I like what you say about ‘lights along the way’. That’s true.

The titles are a bit on the obscure side, but I hope that anyone with a chance to see them would delight in the way they go about being distinctive. It is getting harder to see older world cinema titles on TV, though The Last Black Man in San Francisco was shown on BBC Two a short while ago. I learned so much from what was broadcast as a matter of course in the late hours in the late 70s/early 80s. But many such films are out there on disc or steaming (which we could never had imagined forty years ago), and the Sight and Sound poll is a great encouragement to see out some of them. There are so many films listed there than I’ve not seen – and several I’ve not even heard of – which I must seek out. So lists work after all.