One of the cinema’s great gifts to us all is the closing shot. Each art form becomes distinctive through its ability to tell stories through devices unique to itself, and so there is nothing in the novel, theatre, opera or any other dramatic method that has anything to compare with the closing shot of cinema. Where something similar does occur, it is invariably a failed attempt to capture that which belongs only on a screen, at the end of a story of around two hours, whose meaning for its audience must always lie beyond words.

Not every film has a memorable closing shot – indeed most do not – but those that we cherish help define the medium. Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard silhouetted as they walk away from us down a road in Modern Times; Alida Valli walking past and ignoring Joseph Cotten at the end of The Third Man; the solitary John Wayne, grasping his arm, as he passes through the door of the homestead in The Searchers; the young Jean-Pierre Léaud running into the sea with the freeze-frame on his bewildered face in Les Quatre Cents Coups; the shoot-out in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; Klaus Kinski alone on a swirling raft, his mad dreams all dead, in Aguirre, the Wrath of God – are iconic in themselves, but show how cinema can resolve itself, at the end of those two hours of storytelling, into a single, lingering image. All that we have seen, or all that we have to learn from what we have seen, is contained in the shot that will most powerfully imprint itself on the mind. It is time collapsed into a memory.

I thought about closing shots when hearing yesterday of the death of the Czech film director Jiří Menzel. The films he was allowed to make were too few, but three of them enjoyed the highest acclaim: Closely Observed Trains (1966), Capricious Summer (1968) and Larks on a String (1969). The first two, products of the marvellous Czechoslovak new wave of filmmakers and the political thaw of the Prague Spring, are bittersweet comedies that were widely seen at the time. The third, Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti), was made as the Soviet tanks rolled back in, forcing it to be banned before any screening. It was not seen officially until 1990, the year after the Velvet Revolution, when it shared the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Larks on a String, one of my favourite films, has one of the greatest of closing shots, and is therefore by definition one of the greatest of films, since the one cannot be without the other.

The film is set in a scrap metal yard in the Communist Czechoslovakia of the 1950s, a time of leaden Stalinist ideology, political purges, labour camps and show trials. A group of political dissidents works, in desultory fashion, at the yard: a librarian, a philosopher, a saxophonist, a barber, a dairyman, each condemned for having thought the wrong way. The objects they recycle are reminders of a ruined past, much as they are themselves. All must be smelted into something new. Every now again one of them asks someone in authority why things are the way they are. In the following scene we learn that he who asked the question has disappeared. So the next in line has to ask the question.

But though set against the bleakest of circumstances in the most unpromising of settings, this is a lyrical and uplifting film, filled with humour both sad and mischievous. It is beautifully shot – cinematographer Jaromír Šofr conjured up shots of exquisite colour amid the piles of rusting metal in the scrapyard, of which the grimy dissidents seemed almost to be an organic part. Amid the absurdities of ideology (a group of children is taken to see the dissidents, their earnest teacher pointing out the sad and kindly women as having “repugnant, imperialism soaked faces”), the men ponder philosophical questions, keeping understanding alive.

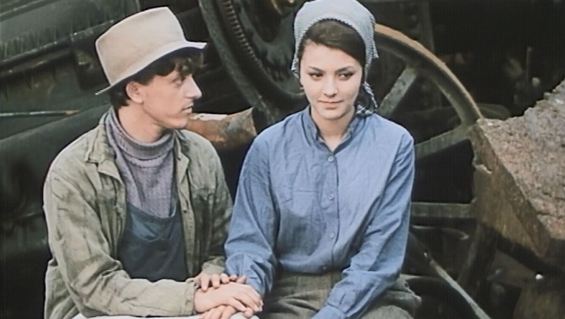

Fleeting romance occurs between the separated male and female detainees, in which the light touch of hands as they tenderly pass pieces of metal between them as part of a chain has a blissful edge to it. The women’s guard, a sad young man married to a disaffected Roma, becomes entranced by a sentimental painting of an angel he finds on a scrap heap. Becoming a guardian angel himself, he furtively allows them the little happiness he cannot find for himself. In every scene, the prison in which they find themselves is undermined by minds that question and hearts that beat true.

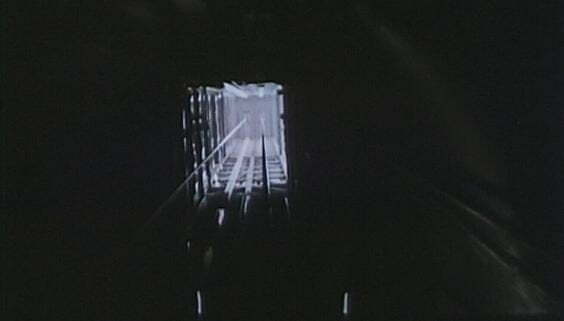

A young man among the dissident group, Pavel (played by Václav Neckář, the hero of Closely Observed Trains), falls in love with one of the women. He marries her by proxy, but before the marriage can be consummated (again at the guard’s connivance), Pavel is hauled away in a car for having asked the question about why some of his number have disappeared. Our last sight of him is in a mining party. Before they go under the ground, he sees his bride Jitka (played by Jitka Zelenohorská) bidding him farewell. The mineshaft lift hurtles downwards. One of those who had disappeared, the philosopher, is in the cage. He ends a disquisition with the words “I am happy, I have found myself”.

Elated by love and truth, when he should be suffering punishment for questioning the state, Pavel looks up. He sees the bright light above shrinking as his party descends into the depths, a receding sign of hope that only seems to increase as the light grows smaller. It perfectly encapsulates all that has taken us to this point. It is defeat, hope and irony all in one. It is symbolic of the film itself, which was consigned to darkness before it could be seen, yet had such light and life within it. The day would have to come when it would be seen again.

Like film, like country. I saw Jiří Menzel once. It was at the National Film Theatre, probably the screening of his film My Sweet Little Village at the 1986 London Film Festival. It was when the protests in Poland were making us sense that the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe was failing, but before the Velvet Revolution overturned the one-party system in Czechoslovakia. Menzel was asked if change might come to Czechoslovakia. Unable to commit himself, yet equally unable not to look up and see hope, Menzel said that his country was like a sleeping beauty, only waiting to be wakened, at who knew what time. It was but three years away.

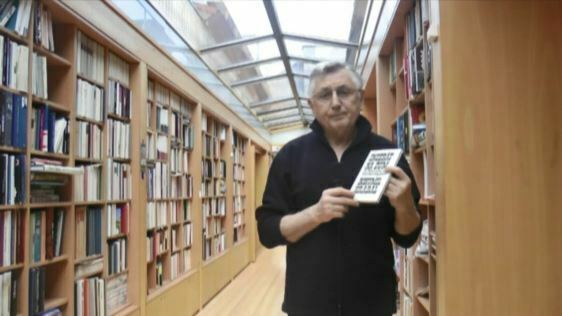

That bleak era has gone, to be replaced by the troubles of our own times. Larks on a String can be seen on DVD, and included on the 2011 Second Run release is a short, self-filmed interview with Menzel. He has a comfortable home. I admire his bookshelves. Things ended well enough for him. He looks back on the film’s history, comments wryly on its recovery, then ends with a mild tirade at modern cinema, which he finds too fond of violence and digital trickery. It is an old man’s complaint, but his recollection of cinema as being at its best when it showed compassion is something to make us think.

Compassion is what Larks on a String is all about, and compassion lies at the heart of that extraordinary closing shot. It says everything about the nonsensical prisons that we continually build for ourselves, and how we must always see beyond them. It is the perfect end to the finest of films.

Thank you Jiří Menzel. Do see the film if you can.

A version of this post is included in my book Let Me Dream Again: Essays on the Moving Image (Sticking Place Books, 2025)