Nine years ago I started up a website that gathered examples of eyewitness testimony from people going to see motion pictures. I called it Picturegoing, which felt catchy, and the dot com address was available. Today, I am happy to announce, the book version has been published.

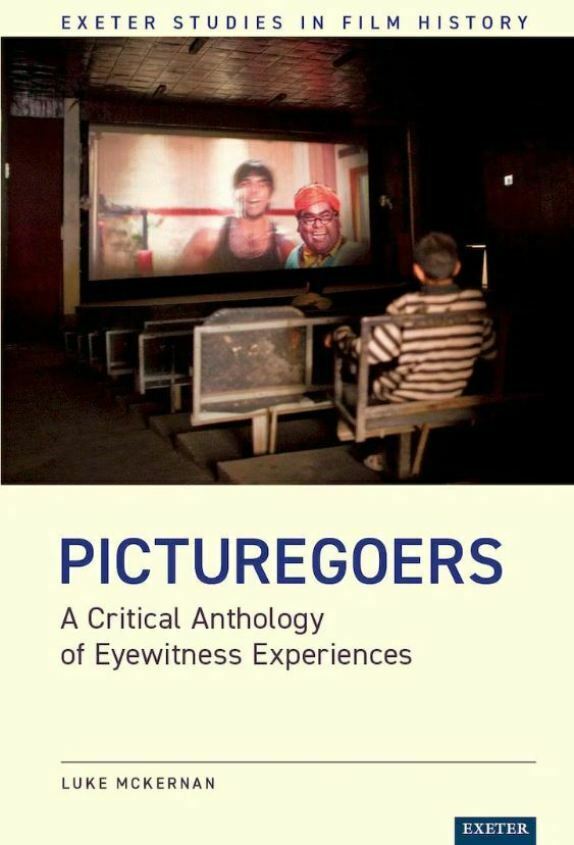

The book is entitled Picturegoers – because a reader employed by the publisher to review the text thought that this was a more accurate reflection of its contents. Its full title is Picturegoers: A Critical Anthology of Eyewitness Experiences, because it is aimed at the academic market, so it needs to look useful to students (which I very much hope that it will be). It’s published by University of Exeter Press, and costs beyond that which the average book-buyer would be likely to pay, but the primary expectation is that it will be purchased by academic libraries, who expect these sort of prices, and so reach more readers that way. I hope so, because I think it useful, and I think it is fun and original (or at least unusual).

The rationale behind the book is expressed in the front cover image. It shows an Afghan boy watching a Bollywood film at a cinema in Kabul in 2011, after the fall of the Taliban (and before their rise again). He is wholly engrossed in the dream world being projected on the screen. He could be any child, any viewer, from the any time or place in the history of motion pictures, yet his experience is profoundly linked to a particular time and place. He is representative and specific at the same time.

We don’t know the boy’s name, or what he thought about the film, but Picturegoers is full of such eyewitnesses who tell us about their picturegoing experiences. There are 114 of them, ranging from the 1890s to the 2020s, and from all corners of the globe. The testimonies come from diaries, letters, oral history interviews, memoirs, travel books, newspaper articles, social surveys, poems, fiction (where it is obviously based on the writer’s experiences), blogs and talks.

In general, the eyewitnesses do not say much about particular films. Instead they write about films in a general sense, or on how the audience behaved, or what they ate and drank, or how the seats felt, or what the weather was like. They recall what went on in their head. They remember that which was memorable to them. They see what is on the screen but also what is all around them. They place the idea of cinema specifically and generically.

There are some famous names among them. Jean-Paul Sartre’s memories of going to Paris cinemas as a child in the 1910s are magical. Virginia Woolf ponders the mysterious nature of film reality. Arthur Ransome witnesses propaganda films shown on Bolshevik agit trains. Nelson Mandela gets nostalgic about the familiar black actors he sees in South African films screened on Robben Island (but also quite liking Sophia Loren). But there also many anonymous or little-known eyewitnesses, from Police Sergeant George Jordan reporting on the supposedly dubious London cinema shows he finds in 1909, to anarchist Fermin Rocker recalling how when watching westerns his sympathies were always for the Indians, to African-American Mrs K.J. Bills expressing her amazement at the imposture of The Birth of a Nation, to one of my favourites; known only as ‘Negro male student in High School. Age 17’ who in 1933 writes so eloquently of his hopes and fears when at the cinema:

Several times on seeing big, beautiful cars which looked to be bubbling over with power and speed, I dreamed of having a car more powerful and speedier than all the rest. I saw this car driven by myself up to the girl friend’s door and taking her for a ride. (I was then eight years old and in my dreams I was no older.) Then too, I saw Adolphe Menjou, the best dressed man in the world, try in various ways to kill me because I had won his title. Perhaps the picture that left the most depressing picture on my mind was one in which a murdered man was thrown over a high cliff from a mountain top. I could see that dead body falling, falling to the rocky depths far below and squash into almost nothing. Some nights I dreamed of falling and other nights I had nightmares from dreaming of the same thing, awoke in a cold sweat, and was not able to go to sleep again till dawn.

The book is an anthology, therefore, with its texts arranged into sections: First Encounters, Audiences, Places, Players, Reality, Fears and Desires. In truth, many of the pieces chosen could have fitted into a number of those categories, but it is useful to think of picturegoing through these building blocks of experience. There are images too, which complement the texts rather than illustrate specific ones, so they reflect they sections in which they are placed.

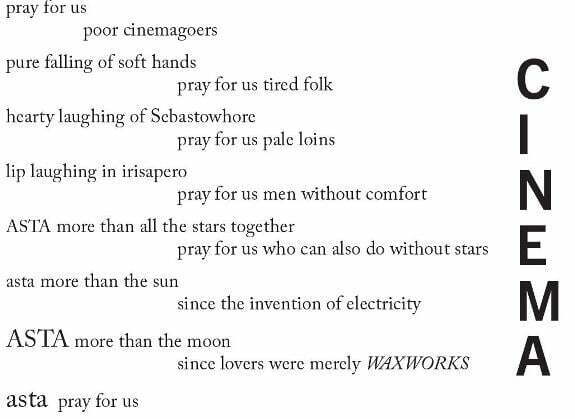

Among the famous names (what fun I had placing George Orwell next to Arnold Schwarzenegger) and the obscure but eloquent others, there are some tour de force pieces. Fintan McDonagh’s English translation of Belgian poet Paul van Ostaijen’s experimental work ‘Asta Nielsen’ (1921) does the poet proud (and top marks to University of Exeter Press for laying out the text so well). Socialite Lady Colin Campbell is completely engrossed in every blow in her vivid account of watching the 90-minute film of the 1897 world heavyweight championship between James Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons. Video games expert Paul ‘Mr Biffo’ Rose writes thoughtfully on how confused our picturegoing memories can be (in his case Star Wars, its sequels and prequels). My nephew Jacob, aged 19 at the time, writes about going to the cinema in virtual reality in the year 3021, as though he were back in the 1890s and seeing this extraordinary medium for the first time. And, supplying the coda to the book, there is author Frank Cottrell Boyce hymning all that is social and special about going to the cinema, as cinemas in the UK came out of COVID-19 lockdown in 2021:

Streaming services have been lifelines during lockdown. They’ve injected fun and inspiration into the long unpunctuated weeks. But it isn’t just films that we’ve missed. We’ve missed these moments, the eccentric, the accidental, the coincidental, the unpredictable, the stuff that life throws at us when it is being life. Most of all, we have missed those shared laughs and screams that say, it’s not just me. You’re not alone. Like that time in a full cinema at the end of Paddington 2 when everybody suddenly applauded. Why? The bear wasn’t there to hear it. The bear is actually just a bunch of pixels. We were clapping for each other, to say, here we are together and we’ve just shared something truly wonderful.

And there you have it. Cinema is about us. Films are there to serve the need. That’s what Picturegoers is about. I hope you get to track down a copy.

Links:

- Picturegoers is published by University of Exeter Press. There is information on the book, including a full contents list, on the UEP website. There is also a Q & A with me on the UEP blog, with Joe Kember asking the searching questions

- The original Picturegoing website is still active and being added to (occasionally). There are many texts on the site that are not in the book; there are many texts in the book that are not on the website.

Wonderful to have this great site preserved in book form!

Thank you Ian, though as I note above, there are many texts in the book that are not on the website, and many texts on the site that are not in the book. They are not one and the same.