So long as that woman from the Rijksmuseum

in painted quiet and concentration

keeps pouring milk day after day

from the pitcher to the bowl

the World hasn’t earned

the world’s end.‘Vermeer’

Poetry is everywhere. It is in the view framed by my window. It is in the cup from which I have just drunk. It is in the arrangement of books, papers and random objects laid across the desk. It is in the carpet, the rug, the floorboards beneath. It looks out at me from every picture on the wall. Maybe at times I sense the poetry, but for the most part it remains unspoken. It needs the poet’s eye to say what may be sensed around us, to find the meaningful in the accidental, to give us the thoughts we had not understood before they were pointed out to us. Ah, now I see the bowl, the pitcher, the woman, the grasp of art’s eternity. I knew that but had not thought it. Thank you.

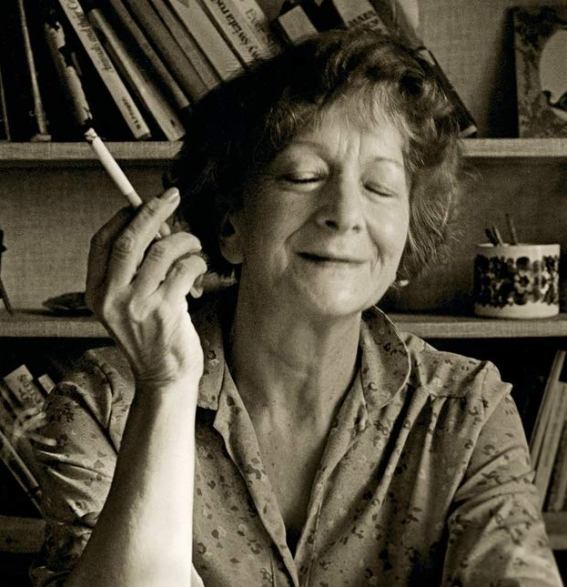

Wisława Szymborska (1923-2012), author of ‘Vermeer’, winner of a Nobel prize in 1996, is a poet of the eternal made manifest in the everyday. Time and again in her poetry she catches the reader’s attention from the start, with an arresting observation triggered by the the kind of mundane thoughts we all can share but few turn into poetry:

Four billion people on this earth,

but my imagination is still the same.

It’s bad with large numbers.

It’s still taken by particularity …‘A Large Number’

It is the poetry of an enquiry triggered by the banalities of modern living. It reveals the poetic world that we, too often unwittingly, actually inhabit, because it is we who must make the poetry:

What needs to be done?

Fill out the application

and enclose the resumé.Regardless of the length of life,

a resumé is best kept short.Concise, well-chosen facts are de rigueur.

Landscapes are replaced by addresses,

shaky memories give way to unshakeable dates.Of your loves, mention only the marriage;

of your children, only those who were born …‘Writing a resumé’

Szymborska was a poet with a very particular voice. Lying somewhere between the sympathetic and the sardonic, given to viewing the ordinary through surprising perspectives, it gives the reader a strong sense of a distinctive, engaging character, who mocks herself as much as she mocks the predicament of everyone. It is as disarming as it can be disturbing. It is the voice of one who has come home from shopping with an unshakeable thought in their mind and the armoury with which to express it.

I first came across her work through one one of her most characteristic poems, ‘Slapstick’:

If there are angels

I doubt they read

our novels

concerning thwarted hopes.I’m afraid, alas,

they never touch the poems

that bear our grudges against the world.The rantings and railings

of our plays

must drive them, I suspect,

to distraction.Off duty, between angelic –

i.e. inhuman – occupations,

they watch instead

our slapstick

from the age of silent film.To our dirge wailers,

garment renders,

and teeth gnashers,

they prefer, I suppose,

that poor devil

who grabs the drowning man by his toupee

or, starving, devours his own shoelaces

with gusto.From the waist up, starch and aspirations;

below, a startled mouse

runs down his trousers.

I’m sure

that’s what they call real entertainment.A crazy chase in circles

ends up pursuing the pursuer.

The light at the end of the tunnel

turns out to be a tiger’s eye.

A hundred disasters

mean a hundred cosmic somersaults

turned over a hundred abysses.If there are angels,

they must, I hope,

find this convincing,

this merriment dangling from terror,

not even crying Save me Save me

since all of this takes place in silence.I can even imagine

that they clap their wings

and tears run from their eyes

from laughter, if nothing else.

In its wry humour, oblique observation, kindliness and bleakness, ‘Slapstick’ shows you what to expect from a Wisława Szymborska poem. The approachability of her style helped make her popular. With seemingly little lost in translation (all of the extracts given here are from her collected poems, translated by Clare Cavanagh and Stefan Barańczak) her voice transcends borders.

Few of them made it to thirty.

Old age was the privilege of rocks and trees.

Childhood ended as fast as wolf cubs grow.

One had to hurry, to get on with life

before the sun went down,

before the first snow.Thirteen-year-olds bearing children.

four-year-olds stalking birds’ nests in the rushes,

leading the hunt at twenty –

they aren’t yet, then they are gone.

Infinity’s ends fused quickly …‘Our Ancestors’ Short Lives’

It’s that borderless voice that feels especially distinctive. It’s not just the themes that may apply to anyone (we are all descendants of those short-lived ancestors), but something in its Polish roots.

Szymborska was a Pole, living through the ravages of the Second World War, the heavy years of Communist rule, and the post-Communist reaction since. She was a party member, writing ideologically-sound works in the 1950s that she later rejected, but even though siding with dissidents thereafter she seems to have retained some sympathies. But her greater feeling was for her neighbours, the Polish people, helpless in the face of the turn of historical events except for the gift of being viewers of absurdity. It is the kind of distance that only the victim can enjoy.

We call it a grain of sand,

but it calls itself neither grain nor sand.

It does just fine without a name,

whether general, particular,

permanent, passing,

incorrect, or apt.Our glance, our touch mean nothing to it. It doesn’t feel itself seen and touched.

And that it fell on the windowsill

is only our experience, not its.

For it, it is no different from falling on anything else

with no assurance that it has finished falling

or that it is falling still …‘View with a Grain of Sand’

Szymborska became greatly popular in Poland, even a best seller. Like her fellow Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, she turned observation from a beleaguered land into something the world understood, not so much by reflecting on incident as by portraying a view. The pride that was felt at what she wrote was not one of nationalism but connection. The world may see itself through us. That is probably why the poetry translates so well. The words must fall naturally into place (though I am sure the translators, like the angels, would laugh at such presumption). Her words are our words. Which is the heart of poetry.

This is the sixth in an occasional series of posts on favourite poets of mine

Links:

- The starting point for discovering Wisława Szymborska (in English) is View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1996). Then move on to Map: Collected and Last Poems (2015). If you want to see the translation at work, her very fine 2009 collection Here has the Polish and English on opposite pages

- The Wisława Szymborska Foundation site (in English and Polish) has a biography, gallery (poet, home, book covers), sample poems, and details of the poetry awards it gives out)