After four months of Coronavirus lockdown, I was able to sit once more in a coffee shop, drink my coffee and read a newspaper. It felt like returning to myself.

The shop was a Costa branch; it’s about fifty yards down the road from where I live. The shop has re-opened for a while now, but only serving takeaways. Now, nervously, it is inviting us to sit down inside. There are fewer seats. The serving area is lined with a high wall of perspex. The staff behind this fortress wear face masks. I go to order my coffee, but one of them, recognising me, starts making it before I can ask for it – a fine memory for creatures of habit. I pay by card of course (I have not handled money in four months). I am asked to give my name and mobile number, because the much-vaunted ‘test and trace‘ system, of using mobile phone apps to track down those who may unwittingly come into contact with someone who has the virus, has been an embarrassing flop. Instead name and number are written in a notebook. Alas, this makes me feel apprehensive about coming back again, for eventually your luck must run out. The call will be made that a person near you has been identified as a carrier, and you will be back in isolation again.

There is a small table with seat facing the wall. I put down paper and coffee and settle back into the mode that I had followed for years until mid-March this year. I take a first sip and glance at the headline stories. Over to the back pages for the reporting of sports that have taken place in ghostly circumstances with no crowds, bar old recordings used for football matches. Backwards I go to the obituaries, then the chess problem (solved in two seconds – the mind feels trim), then the TV listings, then the arts reviews and light features. I am half way through my coffee.

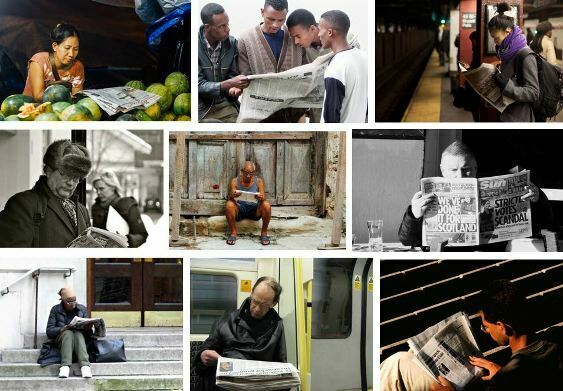

Back to the front page and the news of the day; strictly speaking, of yesterday. During these past four months I have abandoned buying a newspaper and have subscribed to its app form instead. This has much going for it. It loads on my PC, tablet and mobile, it is easy to navigate, I can take it wherever I am, I can save stories for future reading. But opening the newspaper, I see what I have missed. A print newspaper is a work of art in a way that no news app has yet achieved. It arranges the world in space. The eye ranges from story to story, artfully selected from an association of themes on any one page, taking in titles, images, blocks of text in a form that profoundly reflects the subject – news – that it is there to display. One sees the world in a particular arrangement.

The superior eye one has from scanning a newspaper must be why the medium – whose 400th anniversary in Britain falls next year – has been so successful as a provider of news. It gives sense of review and understanding, and, because of this, empowerment. The quality of the news is not important; that’s a matter of taste. What is important is the relationship of eye to page, and of the page to matters at hand. The newspaper is a map, making its readers explorers.

The news app is arranged differently. Headlines, stories and images may be the same, but in general one is presented at any one time. Where they are several stories, as an a news website, one has to click on any one to learn more. It isolates rather than synthesises. Of course, it it offers tremendous facility, but it feels almost destructive in how it breaks up the news into parts, for all that each part may be connected to other through logical links.

I have drunk my coffee. Some stories were read closely. For others, the headline had to suffice. Some I ignored because they too obviously reflected a particular editorial bias. Throughout I am entranced by the astute arrangement of word, theme and image. Nothing jars. I feel that the world, if it is no better than it was, is more understandable. I feel like an observer again.

Held by © Trustees of the British Museum

News and coffee are profoundly interlinked. The coffee houses of the 17th and 18th centuries were where people would gather to pick up newspapers and discuss the latest intelligence with others. Samuel Pepys writes in his diary for 24 May 1665:

Thence to the Coffee-house … where all the newes is of the Dutch being gone out, and of the plague growing upon us in this towne; and of remedies against it: some saying one thing, some another.

The coffee house served as some other, shared place, a refuge from disorder, the focus of concentration. Here one could step away from the onrush of time, recover the spirits and gain an overview. No matter that some would be saying one thing, some another – the strength lay in being an observer. Your being there composed the news.

There is a renowned American sociological study, first published in 1989, by Ray Oldenburg, entitled The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bards, Hair Salons and other Hangouts at the Heart of A Community. Oldenburg advocates the place of escape, the ‘third place’ between home and work, where we may recover ourselves and our sense of community. It has been crediting with helping to trigger the great explosion in mega-chains such as Costa and Starbucks, whose uniformity of offer has been based on the sense of assurance and escape that Oldenburg’s book articulates.

Oldenburg links the coffee house, and other third places, with news. However, looking at the history, he sees the coffee house as a news centre in itself, rather than the place where one discovered news publications – a social rather than an individual function:

The seventeenth-century English coffee house played its major role in the establishment of individual liberty because of a unique combination of circumstances. The place had appeared as a new forum, free of all the encrustations of the past. In the coffeehouse, men [women were excluded] from all parties and stations could mingle in innocence of the old traditions. In the absence of an established press, face-to-face discussion in the permissive atmosphere of these second-storey halls represented a single and vital mode of democratic participation.

This is typical of the idealism that runs through The Great Good Place, but how true is it of news and third places? Is news social? Its purveyors have always wanted it to be so, creating products that link the individual reader (or viewer, or listener) to a particular place, community, sect or shade of politics. But though many find some reassurance in this, deep down news is a private affair. It exists to reassure the individual of their place in present times. It tells them where they are. If the answer is partly that one belongs to a community that shares the same news interests, the need is still individual.

That is why news is structured in the form of stories, because stories are fundamental to how we comprehend our place in the world (as I have argued elsewhere). It is remarkable that the several studies out there on the function of stories from a psychological point of view seem to focus almost exclusively on fiction. News is seldom mentioned, at least as far as my reading goes. Nor do studies of the news talk about the news as a source of stories that people need to read (or view, or listen to). There are manuals that advise on how a news story should be constructed. There is plenty on the powerful effects of individual stories, for good and ill. But news as the supplier of a fundamental neural need for narratives that make sense of out of chaos seems to have been ignored.

Will Storr, in The Science of Storytelling, explains the how and why of our need for stories, usefully summarising some of the intoxicating but unsettling conclusions coming out of recent studies in neuroscience:

In order to tell the story of your life, your brain needs to conjure up a world for you to live inside, with all its colours and movements and objects and sounds. Just as characters in fiction exist in a reality that’s been actively created, so do we. But that’s not how it feels to be a living, conscious human. It feels as if we’re looking out of our skulls, observing reality directly and without impediment. But this is not the case. The world we experience as ‘out there’ is actually a reconstruction of reality that is built inside our heads. It’s an act of creation by the storytelling brain.

We create the world in which we have to live. We do so through stories. It is the only way we can function.

I think there is a grand study to be made of the news story, from the cognitive point of view. It feeds that need for beginning and ending, conflict and resolution, injustice and retribution, cause and effect, that any story must supply, but does so in a way that differs significantly from fictional forms. The news story is subject to the hazards of real time. It is seen, indeed may only function properly, through its relationship with other stories, allowing for lessons through comparison. In this way it profoundly reflects the experience of life, our minds juggling with multiple and sometimes contradictory narratives, in which good is not always rewarded, resolution is not always attained, wars do not end, wealth comes to the undeserving, and the wrong people win elections. News is driven by stories, yet through its form is forever revealing the fragility of our deep-rooted belief in stories.

News also comes with recurring characters. People in whom we have decided to take an interest (maybe because an editor has decided this for us; maybe because what we want to see is what the editor has to follow) appear for a while, retreat from the common gaze, then re-appear. My paper today keeps me informed about the regulars: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, and some that are the current focus of prurient interest – Ghislaine Maxwell, Johnny Depp. But others I had forgotten about have returned – Shamima Begum, Mark Carney, Tracey Edwards, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. I link past knowledge to present news interest (the newspaper takes care to remind me why the person is memorable). Their story goes on, added to my personal store. The news story never ends, unless it is with the obituaries page. The jury is always out, forever waiting to see how the story may rightfully unfold.

Fiction shapes reality to form a lesson. News tries to do the same, but is always confounded by the unpredictable unfolding of real life, where wisdom is provisional and the rewards and punishments we expect are only erratically applied. News offers the human brain (which is only concerned with survival) a far more useful set of lessons than the novel, the film or the TV series. But it is the latter to which we return, because they are shaped to supply security, a world we understand. News, the efforts of news editors notwithstanding, cannot do this. And so we fear the news as much as we need it.

One book that at least hints at how our storytelling brain makes use of the news is The Knowledge Illusion (2017), by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach. Noting, as Storr does, that “storytelling is our natural way of making causal sense of sequences of events”, their arguments on the human need for this touch on areas of identity and community not so far away from Oldenburg’s great good place:

Stories are used to transmit causal information and lessons among people, as well as to share experiences, to organize a community’s collective memory, and to illustrate and announce an attitude. When a community agrees to buy into a particular story, they are accepting the attitude implied by the story. Americans who tell the story of the Sons of Liberty tossing chests of British tea overboard in Boston Harbor in 1773 are telling a story of proud defiance against coercion. When the British traders of the era whose tea was spoiled told the story, they were describing a bunch of thieving hooligans who needed to be taught a lesson. Thus stories generally belong to a community, not to an individual, and they are intimately tied to a community’s belief system.

This would seem to deny the individual’s sense of the news, which must always be tailored to the understanding of a specific community (what is news to us may not be news to them, or is at least viewed differently by them). But news is both communal and individual, which is exemplified through that fundamental reliance on stories. It is our need for stories that forms communities, not the other way around. We dream up our tribes and nations, because we need to. They help form the environment our storytelling brain needs in order to function, to see cause and effect in operation. This is why we have our news media; this is what the newspaper, in its very form, does so very well.

This leads me to one more book. The Form of News, by Kevin G. Barnhurst and John Nerone was published too long ago (2001) to learn from recent advances in neuroscience, and in any case its interest is the changing civic engagement with (American) newspapers, seen through the forms newspapers have taken. But they do think of readers as much as news producers, and they do point to how news functions for our storytelling brains:

[News] inscribes its own readers. Just as it hides its own form, the newspaper proclaims its readers to be sovereign individuals, self-conscious users of transmitted information about the world. Critical scholars object to this account, arguing that information is presented in ideologically fraught forms, but they imagine that ideological effects occur because readers read ideologically constructed stories and pictures. This account also misses the mark. Readers do not read bits of text and pictures. What they read is the paper, the tangible object as a whole. They enter the news environment and interact with its surface textures and deeper shapes. Readers don’t read the news; they swim in it.

I read this as saying that all news is a story. The news medium creates the form through which an unending river of news can flow. It mimics the brain, which must deal with the chaos of information that confronts us every day and find reason through narratives that must reassure us. Individual stories may confound our sense of how things should be, but they do not change it. We simply move on to the next story, expecting that this will be the one that confirms our expectations. It’s a constant battle.

There are other ways to define what news means for us. Most importantly there is its currency, because old news is, literally, history. It functions through a story-led paradox: our desire to be told new things through that which is familiar. These must be recognisable stories that are ongoing, that have not yet reached resolution. Our satisfaction – our need – lies in sensing how they will turn out. If that does not always happen as we would expect, no matter. The next story is waiting for us, on the same page, or the next. The news keeps us reading (and viewing, and listening), forever challenging us to identify ourselves.

My coffee being drunk, I must leave. I know my money has paid for space and time more than it has paid for a brown frothy liquid, but a drained cup tweaks the conscience. I take the news with me, folded under my arm. I must pursue those stories further.

Links:

- The books referred to in this post are Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bards, Hair Salons and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (New York: Paragon House, 1989); Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling (London: William Collins, 2019); Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach, The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone (London: Macmillan, 2017); Kevin G. Barnhurst and John Nerone, The Form of News: A History (New York: The Guildford Press, 2001)

- On newspapers and coffee houses in the 17th and 18th centuries, see Matthew White’s article for the British Library, ‘Newspapers, gossip and coffee-house culture‘. On coffee house history in general, see Markman Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004)

- For some head-spinning accounts of the new discoveries in neuroscience see the works of David Eagleman (The Brain, Incognito) or Bruce Hood, The Self Illusion: How the Social Brain Creates Identity (London: Constable, 2011)

Thank you for this; good thoughts and good links.

I teach journalism and engage in the heresy of questioning the story as its basic form. I have seen the story become seductive. See this on the Spiegel storytelling scandal:

https://medium.com/whither-news/the-spiegel-scandal-and-the-seduction-of-storytelling-bfed804d7b21

And give what you’ve written here, if you haven’t yet seen it, I think you might enjoy the book How History Gets Things Wrong: The Neuroscience of our Addiction to Stories. I wrote about it here:

https://medium.com/whither-news/a-coming-crisis-of-cognition-df11af616c77

Thank you for this. The Alex Rosenberg arguments look particularly interesting. However, I think how we understand things as stories and how to write persuasive stories (or beyond stories) are different things. Will Storr’s book goes on to consider how to write film scripts. This is interesting, as are the ideas on new kinds of journalism, but the storytelling need still remains, no matter what we create to feed it. The reliability of it can be questioned, but as a survival mechanism, it has been proven to work, because after millions of years we’re still here. Just about.

It’s good to see that these arguments are being made in journalism studies.

Great tour d’horizon of how we process the world through storytelling and consumption. But coffee shops ain’t what they used to be: mostly full of folk communing with their Macbooks. Maybe they’re scanning news-sites, but i think the coffee shop is less a social hub than a digital one today. For some more recent cognitive work on storification, see intro to my 2019 AUP book, Stories, now online.

And here’s the link to that:

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/28448