There can hardly be a better place for observing the continuum of history and time than the Medway valley. While life may appear to have slowed to a standstill in these days of lockdown, brought about by the coronavirus pandemic, everywhere I turn there are the layers of time, as though looking at an exposed mountainside and seeing the past recorded through succeeding geology.

Located at the crossover point of the road to London and a sheltered, curving river close to the sea, my home town of Rochester has been a focal point for peoples, armies, industry and transportation for millennia. If I stand outside my door, the town the Romans built is beneath my feet, parts of its walls still visible in places. The layout of the houses in my half of the high street follows that of Saxon buildings. Round the corner, the Norman cathedral (built on the site of an Anglo-Saxon original) drew in wealth, power and influence. The Norman castle, spectacularly located on a promontory overlooking river and London road, was built by a people fearful of enemies yet welcoming of commerce.

The high street and adjoining roads have buildings from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries, often one style laid upon an earlier one, but predominantly Victorian in aspect, kept by order to preserve the Dickensian heritage. The river flows in an s-bend around the town to the dockland areas on which so much commerce was based, capped by the naval dockyards at nearby Chatham. A canal was laboriously cut through the chalky Hoo peninsula to lessen the time it took to transport goods to London, only for its tunnel to reassigned for the railway as one transport technology buried another.

The dockyards are a shadow of their former selves, the navy now departed, but in the land vacated thousands of new homes are being built, to be occupied by young people seeking space outside crowded London, lured by the promise of riverside views and the high speed train. The HS1 train takes them over a bridge that has stood – in different incarnations, and shifting locations – for two thousand years, bearing traffic to and from the metropolis, while the river it crosses bore goods from dockyards to the lands within.

Walking away from this historical palimpsest to follow the river Medway upstream, one sees further evidence of the layers of time. New housing stretches for a mile along the river’s southern side, before scenery half bucolic, half neglected takes over. The Medway valley was, until recent times, quite heavily industrialised, with lime kilns, cement works and the giant paper mill at Aylesford. Now those industries are mostly gone, leaving wrecks of boats and factories. But into this space come people. Peter’s Village has sprung up out of nothing in a couple of years, and with it a new bridge across the river where right up to the 1960s there were only humble ferries.

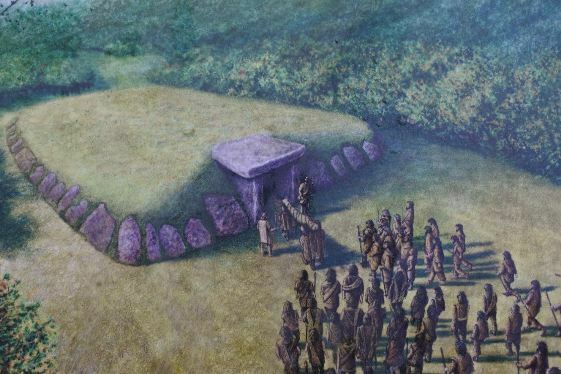

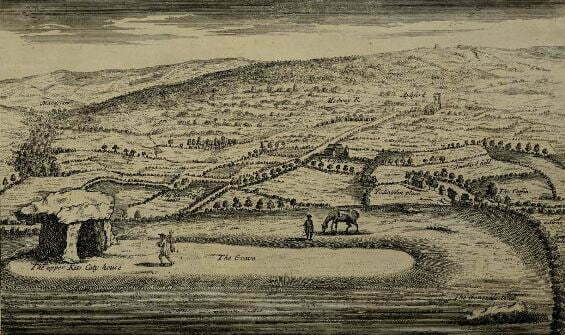

At Aylesford, turn left and up the valley slope away from the river, for evidence of a time against which the Romans feels like recent interlopers. About three-quarters of the way up, in a field close by woodland, stand four stones. There are three standing stones, with a capstone atop, together standing over ten feet high. Surrounded by Victorian railings that give the edifice an incongruously municipal air, it is what remains of a Neolithic chambered long barrow, constructed somewhere between 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. It is older than the pyramids.

It was originally positioned at the eastern end of a long burial mound, now gone, but calculated to have been some 80 metres long and up to 15 metres wide. There would have been a frontal part to to the chamber, while kerb stones (some of which might still be lying in the surrounding field), fringed the edge of the mound.

Kit’s Coty House may have acquired its quaint name from an Ancient British word for forest (at the time of its construction the Medway valley was a thickly forested area). However, it might equally have come through a muddled sense of history from Saxon or later times, when it was thought to have been the burial place of a supposed British prince Catigern, who was said to have been killed in a battle with Saxons at nearby Aylesford in AD 455. Certainly that was the case in 1576 when William Lambarde published his A Perambulation of Kent, giving this account of the structure and its name:

The Britons … erected to the memorie of Categerne (as I suppose) that monument of foure huge and hard stones, which are yet standing in this parish, pitched upright in the ground, covered after the manner of Stonage (that famous Sepulchre of the Britons upon Salisburie plaine) and now tearmed of the common people heere Citscotehouse.

The belief that Kit’s Coty House was Saxon in origin persisted into the seventeenth century at least. On 24 March 1669 Samuel Pepys was a visitor and was fed the standard information:

And so, staying till about four o’clock, we set out, I alone in the coach going and coming; and in our way back, I ’light out of the way to see a Saxon monument, as they say, of a King, which is three stones standing upright, and a great round one lying on them, of great bigness, although not so big as those on Salisbury Plain; but certainly it is a thing of great antiquity, and I mightily glad to see it.

We know far more about its history now. We know that it was built by people from the earliest farming communities in Britain, dating from the Neolithic era. We know that it was a communal burial mound, likely to have been a focal point of community identity and worship over a considerable period. We know that it was one of many such megaliths, of which four others survive, in various states, in the Medway valley. A kilometre of so down the slope, tucked away almost out of view off a main road on the edge of a field lies Little Kit’s Coty House, a pile of twenty stones that would have been an impressive sight until its collapse in the late seventeenth century. On the other side of the river, at Addington and Trottisliffe are Chestnuts Long Barrow (on private land), the collapsed Addington Long Barrow, and the splendid Coldrum Stones, perched on top of a slope looking out over valley and river as though contemplating the vicissitudes of time.

Since the 1880s Kit’s Coty House has been protected as an Ancient Monument. One can see evidence of previous disrespect in the Victorian graffiti to be found on the central stone, but the marvel is how it has survived at all. Other megaliths were destroyed or damaged centuries ago, and the mound and kerbstones of Kity’s Coty House have gone. The Saxon legend must have helped sustain its hallowed status since medieval times, but by then it was already some four thousand years old.

How does any human-built structure last so long? How could it survive weather, the depredations of armies, the anger of those upholding a different religion, petty vandalism, or the simple desire for building materials? Today, we build nothing to last. We know that all we construct will come down in time, sometimes all too short a time. We live for the minute and build accordingly. Those who constructed Kit’s Coty House meant it to last for all time; they could not think otherwise. Our buildings last as long as our imaginations.

I know no more of Neolithic society than Wikipedia can tell me. Expert people have written fine studies of megaliths (while others of a more fanciful bent have produced more romantic studies). I see only a structure, old beyond imagining, that looks out on time and the world. For that is what they did. To me it is telling how Kity’s Coty House, Coldrum Stones and other megaliths were not positioned at the tops of hills but partway down the slopes. They are encompassed within the valley. They were built at a time of constant danger, for a land through which a river flowed, attracting commerce and so conflict. Armies met at the natural barrier that was river, as the Roman did in confronting the Ancient Britons, as did the Anglo-Saxons, and then those against whom Rochester Castle was built as a fearsome defence.

Over the tops of the hills that line either side of the Medway lay the enemy. Those within the valley may have traded with them on occasion, but for the most part those people were the other. They belonged to other worlds, they may not have been even viewed as people at all, but malign forces. Home and the world lay within the valley, that which you could see and command. To position your most sacred sites at the highest point would have been to be looking over into darkness. Far better to be located within the valley, looking out to where the river flowed, the known lands stretching out on either side. Here one could imagine time as unending. Look out, and there you see the river traffic, the forests cleared for farmland, the changing houses, the ferries, the bridges, the horses and carts, the smoke of the factories, the dockyards, the sailing ships and steamships, the canals, the railways, the ceaseless parade of the motor cars, and the high-speed rush of HS1, moving us on faster, ever faster, while time itself may not be moving at all.

Links:

- The Wikipedia page on the Medway Megaliths links to individual pages for each of the sites, including Kity’s Coty House, Little Kit’s Coty House and Coldrum Stones

- There is thorough and comprehensive guide to megaliths worldwide at the Megalithic Portal, which has a page on Kit’s Coty House

I’ll be right there. 6 ft. Apart. Masked.

I’ll look out for you.