I read a lot of books in 2019. I bought more than I read, but those are almost separate pleasures, two different kinds of discovery. One is a quest, the other an exploration. I guess that the linked goal is a search for an ideal: the pristine copy, or one that has aged gently, tastefully designed and typeset, a pleasure to handle and to view, and then the reading that shows absolute command of theme and language and, ultimately, time. And so I must always be seeking.

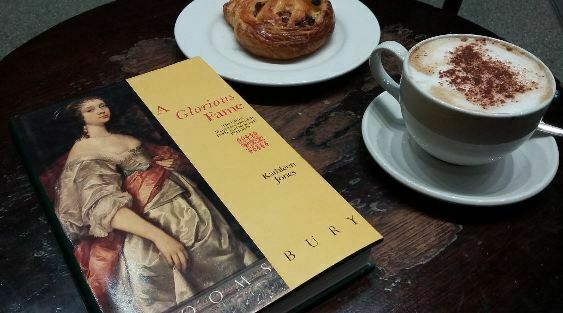

Here are twelve books that I enjoyed finding and reading over the year. Just to be whimsical, they are in chronological order of having been read, one per month. Each comes with one of the drinks that accompanied the reading, for more of which see my Flickr album #thebookimreadingthedrinkimdrinking.

January. As a general rule, you can gain the measure of the writer and the book in your hand from the first paragraph. Wittingly or unwittingly it sets out the stall, letting you know what the journey ahead will be like (should you choose to take it), and whether you will find the company congenial. With the right sort of writer (the sort that is right for you, of course), you know that they are going to be a sure companion on any occasion, that anything they write you will be able to take up with confidence, certain of enjoyment and a good lesson learned. So I was delighted to come across Kathleen Jones for the first time through A Glorious Fame, a spirited and engaging biography of Margaret, Duchess of Cavendish, mid-17th century poet, dramatist, science fiction pioneer and lavish self-publicist. She was ridiculed at the time by her peers for her fanciful airs, but also for daring to want to be a writer (at a time when few women were given either the opportunity or allowed the education to enable them to be writers). Posterity has been kinder, recognising her determined independence and imaginative gift. I went on to read Jones’s A Passionate Sisterhood: The Sisters, Wives and Daughters of the Lake Poets (the author lives close to the Lake District), which is every bit as readable and instructive. I shall be seeking out more.

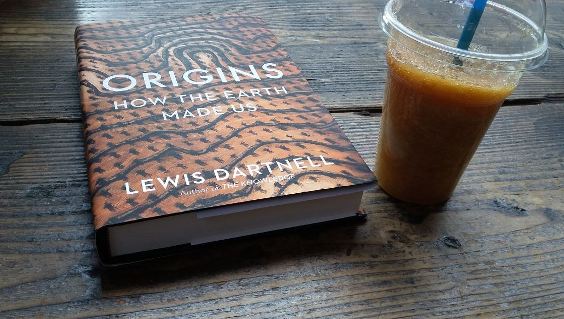

February. I read Lewis Dartnell’s Origins, a fine exercise in big history, while visiting Athens. According to Dartnell’s overarching thesis (“the Earth made us”), just looking at the Mediterranean coastline can tell us why civilisations mostly flourished on its northern side rather the southern. The northern side is rich in inlets, headlands and coves, ideal for seafaring societies, such as that of Ancient Greece, where sea travel was easier and faster than going overland; while the African coastline offered few protected natural harbours. So, thanks to plate tectonics and other such geological turmoil from many millennia past, Athens and Greek society flourished. And so the argument goes on – the very mountainous terrain of Greece can be argued as having led to democracy, by maintaining the tense interdependency of the Greek states. Ranging over the centuries, he shows how geology has ended up determining voting patterns in the UK and the USA. And there you were thinking that you enjoyed free thought, when it is the ground beneath your feet that has made you what you are.

March. It was only after I returned from Greece that I cam across Dilys Powell’s An Affair of the Heart. I know Powell’s work as a film critic well – indeed, I have been around long enough that I can remember her civilised film column in The Sunday Times. But I knew little of her strong attachment to Greece and Crete, which originated in the archaeological digs she attended in the 1930s with her first husband, Humfry Payne. The book focusses on the Heraion of Perachora, an archaeological site to the north east of Corinth, which she visited before and after the war. It has a feeling for place, time and people that marks it as being among the best of travel books. Powell writes so engagingly, and with such style. You sense the English language sighing with contentment at finding itself in the hands of a true practitioner. I also like her several admissions of walks where she misjudged distance and direction, getting lost and miserable. A fellow spirit. I know where I shall be going when next I visit Greece.

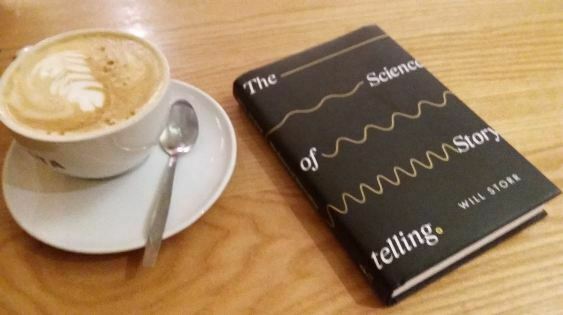

April. Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling is a timely publication as far as I’m concerned. I’ve become increasingly interested in the human need for stories, partly through exploring film subjects on this blog. There are any number of guides out there to finding the ideal narrative for that film script which is going to make your fortune, but these seldom touch on the advances in neuroscience in this area. This is what makes Storr’s book so compelling. He combines instruction of the craft of storytelling (with a strong emphasis on film) with science, making arguments about the underpinning of the brain which feel not dissimilar to Lewis Dartnell’s thesis about geology and climate determining society. Stories, he argues, exist to save us from the chaos that surrounds us. “It feels as if we’re looking out of our skulls, observing reality directly and without impediment. But this is not the case. The world we experience as ‘out there’ is actually a reconstruction of reality that is built inside our heads. It’s an act of creation by the storytelling brain.” Without stories, we are utterly lost.

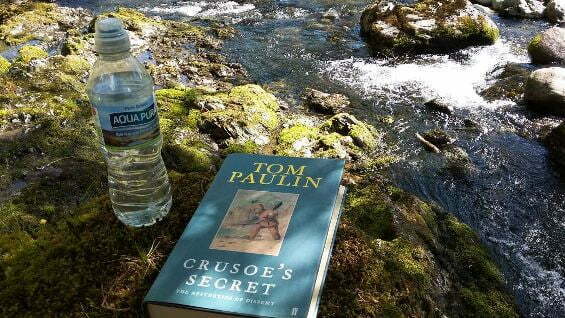

May. Tom Paulin’s Crusoe’s Secret: The Aesthetics of Dissent was my holiday reading over two blissful, if somewhat footsore, weeks in the Lake District. It’s a beautifully produced volume, courtesy of Faber & Faber, only slightly impaired by a binding error in my copy, which has half of one chapter missing and half of another repeated. But it’s signed by the author (specifically, one chapter on Kipling is, so on balance I’ll hold on to it). It’s a series of essays on the tradition of dissent in British and Irish literature. Paulin sees absolute trends where others might find things more open to different interpretation, but the passion and the confidence are compelling. Equally compelling is his microscopic analysis of poetic form and the origins of words. Again, you wonder if the writers under investigation (Bunyan, Defoe, Blake, Hazlitt, Hopkins, Joyce, Elizabeth Bishop and – bizarrely – David Trimble among them) were completely aware of the etymology of the word choices to the degree that Paulin insists, but there is always the possibility, and the thrill that comes with this. The photograph shows book and drink beside Newlands Beck in the very heaven on earth that is the Newlands Valley. I must return.

June. I was so pleased to find this rarity (in the excellent Oxfam bookshop in Canterbury, since you ask – there’s nothing quite like an Oxfam shop in a town with two universities). Hazlitt Painted by Himself is the autobiography that William Hazlitt never wrote, or at least that’s the conceit. In 1948 editor Catherine Macdonald Maclean collated autobiographical passages from Hazlitt’s writings, merging and reshaping these as chapters on such themes as his childhood, acquaintance with the Lake poets, political feeling, artistic interests and love, in a manner that suggests a cohesive text designed by Hazlitt himself. It doesn’t work entirely well, not least in giving too little attention to Hazlitt’s thoroughly mismanaged romantic life, but the idea itself is so pleasing. Someone should have another go.

July. Alberto Manguel never disappoints. Fabulous Monsters, his latest work, is an easy study of the literary characters that live on with us from childhood, or at least if we are exceptionally well-read children of the kind that Manguel must have been. There are short, wryly observant chapters on such figures as Little Red Riding Hood, Captain Nemo, Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, Faust, Satan, Queequeg and Heidi’s Grandfather, accompanied by Manguel’s own, somewhat twee illustrations. It is as much an exercise in nostalgia as intellectual exposition. Manguel mentions Harry Potter just the once, in a pained and puzzled sentence. He seems at a loss to understand what makes a fabulous monster for a child nowadays, and can only find comfort in that which he knows he knows. It is a book as much for himself as it is for anyone else.

August. Atlas of an Anxious Man (2012, published in English 2016), by Christoph Ransmayr, does not have the best of titles. Be assured, you should look beyond it, because this was the best book I read all year, indeed is one of the best books I have ever read. Ransmayr is a Austrian novelist and cultural commentator. His Atlas is a set of essays each centering on an incident recalled from years spent travelling the globe, visiting some of its far-flung corners along the way. The places encountered include Chile, Tibet, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Iceland, Yemen, Pitcairn, Japan and Laos. Each essay begins with the words “I saw…” What follows is seldom a literal account of what the traveller witnessed, but rather an impression of moments where the extraordinary jumps out at us, if we have the questing spirit and the eye to see it. It is astonishingly observant – a guide to a lonely planet like no other. I have since read his novels The Terrors of Ice and Darkness (on a nineteenth-century polar adventure, rather fine) and The Dog King (an alternative post-war German history, something of a misfire) and have The Last Word, reportedly his best novel, lined up for 2020.

September. The best new book I read in 2019 was Caroline Crampton’s The Way to the Sea: The Forgotten Histories of the Thames Estuary. Maybe there’s a touch of local bias in my choice, given that her subject is a journey down the River Thames, with particular focus on its lower reaches, down to those parts of the North Kent coast that I know so well. Perfunctory in the attention she gives to the upper reaches of the river (so lovingly documented by other writers), she instead devotes passionate detail to the grey, muddy, neglected, ostensibly unlovely estuary as the river spills out into the North Sea. She weaves in personal history – her parents sailed from South Africa to settle by the Thames, her father rose to become chief executive of the port of Sheerness – with the social in a form that could have been self-indulgent, only she gets the balance just right. It is remarkable how many ways she find to describe the mechanics and the feeling of journeying by water. I feel sure that it will have inspired many of its readers to take a walk out of London alongside those neglected waters, or to sail if they can. A first-rate exercise in adventure close to home.

October. It’s fascinating to see the number of books published in recent years which focus on discovery when one would have thought that every corner of the planet, at least those parts above water, had been mapped and measured. But we need to know that there are still things to be discovered. As I wrote earlier this year about such books, “We need the hope of discovery, the paradoxical assurance that we do not know everything. To know every corner is to lose imagination, even to lose hope.” Some of these books map romantic, far-away places, appealing to the ‘bucket list’ crowd. Some map the purely imaginary, places like Atlantis once dreamt of but destined never to be found in reality. Others tell us about what remains strange, elusive or unknowable even in the age of Google Maps. Such is Alastair Bonnett’s Off the Map: Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands, Feral Places and What They Tell Us About the World, published in 2014. This is an engrossing guide to abandoned cities, disappearing islands, breakaway nations and no-man’s lands, each of which challenge our idea of how the world is made up and what our maps reveal. It could have done with some illustrations (maybe the paperback has some?), even maps, futile as they would sometimes be. But it is a great read, even if it is unclear just how many of these peculiar places the author has actually visited. It is exploration by Google.

November. I have this guilt feeling about novels. I ought to be enjoying them, because that’s what other people do, but I find them puzzling, or at least not the best use of my reading time. True stories have so much more to offer than imaginary ones. But I got through some, including the Christoph Ransmayr titles mentioned, and this, Charlotte Lennox’s 1752 work, The Female Quixote. There’s a mini-genre of novels that place a Don Quixote-like character in a modern world, for the purposes of satire. Salman Rushdie did so this year with Quichotte (his hero has his head turned by US TV shows, which he believes are completely true), which after a sparkling first chapter, goes rapidly downhill – I gave up halfway through. Richard Graves’s The Spiritual Quixote (1773) is a charming if slight joke on Methodism. The best of the sub-genre is Graham Greene’s poignant Monsignor Quixote (1982), in which the central figure is a Spanish parish priest who believes himself to be a descendant of Cervantes’s fictional character. Lennox’s heroine Arabella believes that the romantic novels she reads are the primary guide to life. The confusion she causes is comic, though repetitive, leavened by some elegant and witty writing. The problem with these Quixotic novels is that their purpose is comic, whereas Cervantes’s hero is tragic. We do not laugh at him, because in his deluded apprehension of reality we recognise ourselves.

December. Finally, there is the book I am reading now. I took up Herodotus’s The Histories after reading Ryszard Kapuscinski’s very fine memoir Travels with Herodotus, in which he combines memories of early journalistic adventures with a discovery of his craft through his obsessive reading of the Ancient Greek historian. For Herodotus is a shape-shifting kind of writer. He is often identified as the first historian (he wrote in the 5th century BC), but is equally a travel writer, a journalist, and a storyteller. He is a creator of true stories, journeying across much of the known world in search of evidence, but unable to resist recording whatever he is told, no matter how sceptical he may be of its veracity. His primary subject is the Greco-Persian Wars, then of recent memory, but he continually wanders away from what is seemingly the point to describe a land, its peoples, or the rise and inevitable fall of those who would lead these peoples. He is not a historian, in any academic sense, but rather a discoverer, the ancestor of several of the writers I name above, who live and write with the same ambition. Because we do not know everything, so we must go on discovering; and those who can write well and tell us compelling true stories are the finest explorers of all.