A grey but mild day. The rain has gone. There are a few things to seek out in London this Sunday, so I shall set out for a walk around the city.

Train journey, reading Christoph Ransmayr’s novel The Dog King. Ransmayr is my great literary discovery of these past few months, but the novel is a curiosity. I am at that stage of reading for duty rather than pleasure. Only a hundred pages to go.

St Pancras station, filled with people new to London. They proceed with a combination of bewilderment and determination, dragging large wheeled cases behind them.

Down Cartwright Gardens and Marchmont Street, looking at the blue plaques of those who slummed here on the edges of Bloomsbury. William Empson and Richard Greene (commemorated by a pseudo-blue plaque in the window) lived at the same address. What would the author of Seven Types of Ambiguity and Robin Hood have to say to one another? Perhaps they would bond over shared complaints about the creaky staircase.

Stopping off for coffee in Southampton Row. The barista is learning her craft. I put on an encouraging look. Reading yesterday’s newspaper, commentators agog in anticipation of events that did not happen.

Turning right along High Holborn and then down Shaftesbury Avenue. The Odeon just before Cambridge Circus must have one of the most remarkable cinema exteriors in London. It was the Saville Theatre, built in 1931, adapted as a cinema in 1970. Unmemorable within (I have not been there for years, but indeed remember nothing) but above there is an exhilarating friese by Gilbert Bayes showing ‘Drama Through the Ages’, with plaques above depicting ‘Art Through the Ages’. The frieze traces a history of drama from minstrels, to Ancient Greece, Rome, parading through to the twentieth century. In London, always look up.

Memo to self to see if anyone online is documenting all the London friezes.

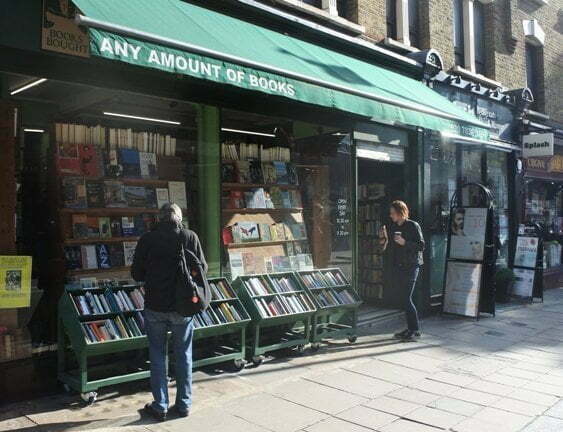

Charing Cross Road. Second-hand books, of course. The street always seems on the verge of losing its line of small bookshops for faceless cafes and boutiques, yet somehow its identity prevails. I restrict myself to Any Amount of Books, always reliable, always too small, but where else in London has more concentrated treasure? Happily at this early hour I have the shop to myself. I come up out with Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Travels with Herodotus and Clive James’s essays on Philip Larkin, Somewhere Becoming Rain. Only published month; who has disposed of it already? Some stony-hearted book reviewer? Their loss, my gain.

Down to the National Portrait Gallery, intending to see the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Sisters‘ exhibition. It is £20 to get in. I recoil in horror, stride out of the building, to the puzzlement of the guard who has just let me in after checking my bag for anything dangerous. £20? I could buy two books for that. I just have – and had £7 change.

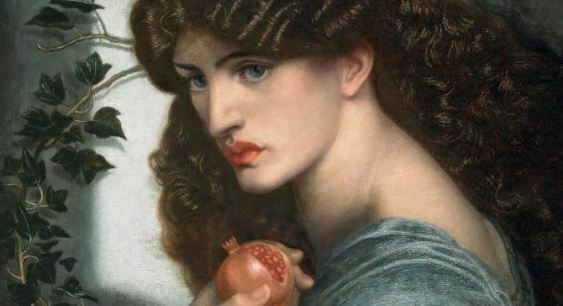

I once saw Jane Morris on the London Underground. It was the early 2000s, while the Pre-Raphaelite model and muse had died in 1914, but there she was, her absolute self. Though young, she had not only the look but that unearthly air of sorrow turning into hauteur that so transfixed Morris and Rosetti. There are various outcomes possible if one leans across to someone on an Underground train and says that they look just like Jane Morris, few of which promised well. So I got out at Embankment, while she sped on, oblivious, disappearing back into history.

Around the corner to the National Gallery. Its peaceful basement area is closed. I must head further afield.

At the head of the Square, tatty entertainment. A man dressed as Yoda rests on a stick, giving the illusion of floating on air. Two people dressed as bright yellow cartoon figure Pikachu. A bearded young man with electric guitar and microphone, singing ‘Wish You Were Here’.

Walking down the Strand. The only plays in London appears to be about plays where things go deliberately wrong. Perhaps slapstick is making an unexpected return. Perhaps this is where theatre dies.

Waterloo Bridge, crossing the river. The City skyline is so ugly now. Well, maybe not ugly as such, but profoundly uncoordinated. Nothing works in relation to its neighbours – each new grand architectural gesture speaks only of itself. It’s a metaphor for something.

Down the steps to the South Bank. To walk alongside a city river is a great pleasure. There is no better way of sensing the majesty of time.

Weaving through the tourists who walk too slowly. A man of Africa plays a kora, transforming busking into something transcendent.

Looking out over the river, I notice for the first time that the columns on the curve of Unilever House aim to echo those atop St Paul’s cathedral.

Tate Modern, a building I have never warmed to. It bears too much the hallmark of its industrial past, a place occupied by art rather than its home. Paintings on the walls feel like squatters.

I find the Bloomberg-funded timeline of modern art, thinking of work projects. It is a giant app, where one taps on an image of an artwork which opens up images of similar works, while small circles which may burst open to reveal other art images float downwards. It gives little concrete sense of art history, but small children love it.

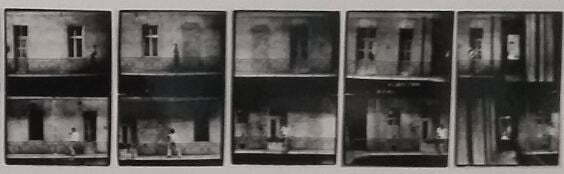

By accident, I stumble into an exhibition by Hungarian artist Dóra Maurer. It is excellent. Witty constructions, photo assemblages, mesmeric films, on the processes of thinking in an artistic way. I am particular taken with photographic sequences that marry Muybridge with the accidental. Two photographers race across apartment balconies, instructed to photograph from the same points as each other, yet fated to be caught out by innate human asynchrony.

Asynchrony. A good word. I had to check the spelling.

A fine, small exhibition. I feel the day, only half gone, has been spent well.

Back across the river over the Millennium Footbridge. I crossed the bridge the week it opened, June 2000. It swung like the deck of a ship in heaving seas as the curious crowd stepped along it. One felt sea sick.

Crowds mill around the walkway to St Paul’s. A Middle Eastern woman in heavy dress and shawl lies prostrate on the pavement. There is no scrap of cardboard and battered coffee cup beside her. Perhaps she is beyond wanting our money. It may simply be utter despair.

A middle-aged Indian man somewhat incongruously plays folk-like tunes on an acoustic guitar. He throws in the odd quarter-tone. An act of defiance.

Around St Paul’s, up New Change then Down Cheapside, stopping for a while to explore the poky charm of Bow Street and statue of the adventurer John Smith opposite St Mary Le Bow. I want to see the statues of Smith and his discovery (and maybe saviour) Pocahontas, brought together. She stands in a churchyard in Gravesend, where she met her end. I have brought them together now.

Turning left at King Street. There is Trump Street to the left. Opposite, there is Prudent Passage. London has a lesson for us at every corner.

Daunt books. So stylish. I look but do not buy. We are in some sort of a golden age of book cover design. I find myself becoming wary of some new books which cannot but fail to live up to the majesty of their jackets.

To the Guildhall Art Gallery. Unpretentious, always reliable. My bag passes through an airport-like scanner. I remain trustworthy.

Above, Victorian works arranged by themes such as Beauty, Work, Travel. Millais’s ‘The Woodman’s Daughter‘ must be the foulest painting in London. Gross in sentiment, gross in execution. How could he live with himself?

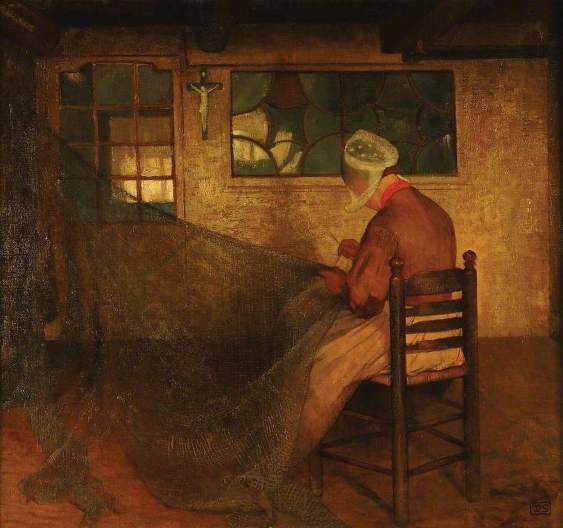

The painting that most catches my eye is Marianne Stokes‘s ‘The Net Mender’. A Pre-Raphaelite acolyte, so an intention part-fulfilled, but this is better than most of the products of that particular soap opera. The curves of the hat echoed in the curves of the glass, the net threatening to swallow up the composition, the golden light of a late afternoon, a hard day’s work not yet done.

Downstairs, an entertaining set of drawings submitted by architects for London buildings that were not approved. Thomas Willson, in 1829, proposed a pyramidal cemetery, to be built on Primrose hill. Ninety-four stories, a base of 18.5 acres. Total burial capacity of five million. Viewing galleries were planned.

Downstairs to one of London’s hidden treats, the Roman Amphitheatre. It was only discovered in 1988, though it was known it had to be somewhere. All that we can see, and walk down, is the eastern entrance tunnel with remnants of walls, but at the end of the tunnel the theatre and its fighters are strikingly set out in green light, green and black paint, vividly imagining lost space and action.

Were they all naked? a young girl asks her mother. Yes. She absorbs this shocking information.

Outside, along Gresham Street, then right down Noble Street. Here a long stretch of Roman wall, looking so matter-of-fact in its survival. There are gardens at the base. Plaques explain how London kept its Roman shape to the 1600s, the city circumscribed by its wall. Walls define the other. Within we understand ourselves. Beyond lie the barbarians. We must always be looking in and looking out.

London is a city of circles. It starts with what remains of the Roman, though within that is the amphitheatre, the circle within a circle, a space where for once the enemy was within and we encircled them, oblivious to the irony.

Then the city of Wren, of Nash, of Bazalgette, of Foster, growing ever more complex and interlocking.

The expanding city of overlapping circles, each the chance for discovery beyond any spurious claim to identity. Journeys through the city may be infinite in number, but they boil down to two types: the linear and the circular. The linear takes us from A to B, from departure to discovery point. The circular marks out a world, created for that day alone, which then disappears. Pebbles landing in a pond.

The roundabout at the Museum of London, as it is now.

Up Aldersgate Street, then left at Long Lane past Smithfield Market, where all is changing. Here will be the new Museum of London. Its thinking will based around time, the promotional site tells me:

the immediacy of real time, the shared experience of our time, the endless fascination of past time, the interrogation of our collections in deep time, the temporary time of changing exhibitions, and the creativity of imagined time …

It’s useful to be told these things, because we don’t always notice.

Along Farringdon Street, posters of pregnant Whipps Cross residents, produced for the Museum of London. Kimberley, Naomi, Anna, Sherrelle, Leila, with future inhabitants.

Holborn Circus. The edges of the City on an empty Sunday afternoon. Places waiting patiently for some life to return.

Past Chancery Lane, along High Holborn, then realise the circle as I turn into Southampton Row again.

Coffee at the same place, but different staff. There is just the right balance of seats occupied and seats free – the escape in space and time. The coffee shop is pure leisure. Ford Madox Ford, in The Soul of London, writes of those points in the city where time moves to a slow pulse and the world stands still:

That is your deep and blessed leisure: the pause in the beat of the clock that comes now and then to make life seem worth going on with. Without that there would be an end to us.

I pick up Clive James. He over-praises that which pleases him, but can only write well.

And so to the railway station, writing notes on the edges of a Guildhall leaflet, thinking that the day could be written out as a set of scraps, who knows why. The clock above, marking completion of another circle.

The rest I forget.

Elegant, and instructive, as ever. I’ve made a few notes too of things to seek out and check up on. When a man is tired of London….?

I avoided saying it, but it is there in every word.