How intriguing to find a temple to Mithras resting underneath a temple to Mammon.

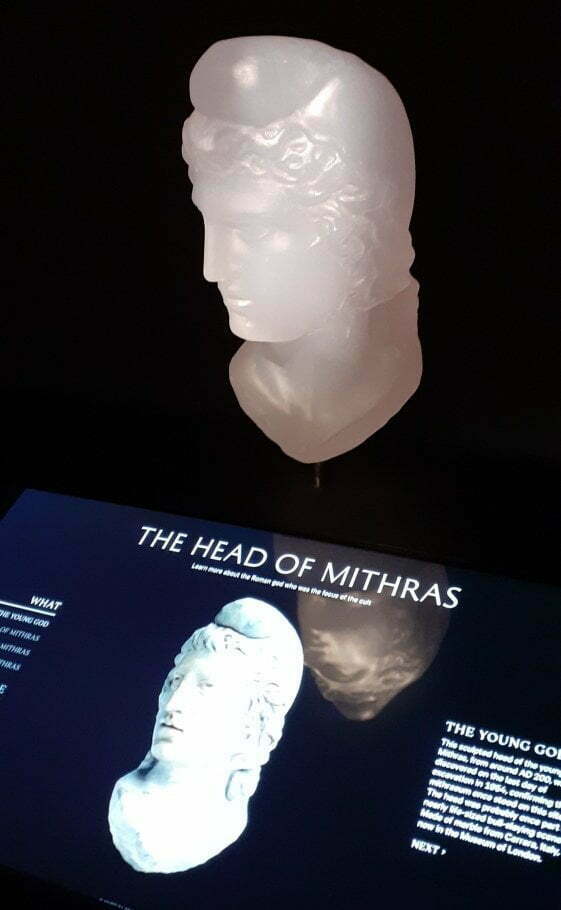

Having visited the Guildhall amphitheatre and the nearby remains of Roman walls the other day, I have got the taste for seeking out Roman London. And so to the Bloomberg building in Walbrook (once a river, now a road) in the City to visit the London Mithraeum. It was in 1954, at the end of excavations on a bomb site, that a head of the god Mithras was discovered, confirming that the building they had uncovered was a Temple of Mithras, the cult figure of a widespread Roman ‘mystery religion’. The discovery excited great interest at the time, as this Pathé Pictorial report indicates:

‘Mithras’, Pathé New Pictorial, issue 530, 8 November 1954

The site was under redevelopment, so the temple remains were dismantled and a reconstruction opened in 1962 around 100 metres from the original location, at Temple Court, Queen Victoria Street. This came under some criticism for its inaccuracies, but it stayed in place until 2010, when Bloomberg took over the site and funded the reconstruction of the remains close to where they were uncovered, building a visitor centre around in the basement of the European headquarters. Temples to Mithras were often built underground, in the basements of other buildings, and though it seems that the London temple was originally above ground, albeit without windows, its resting place feels like an appropriate one.

Arriving at the Mithraeum you first encounter a foyer with some large modern sculptures and an engaging display of Roman artefacts that manages to make even the humblest spoon look exciting. It’s a model example of how to arrange museum objects in space, and it’s a little disappointing that the downstairs area (you go down steps following a timeline of 2000 years, reminding you that the older London gets the further down the layers of time now place it) has nothing comparable on show. There are three small interactives, frustratingly only viewable by one person at a time, and a shadow display of unclear purpose on one wall. The rest is black emptiness, but the primary purpose is to see the Mithraeum, which is adjacent.

You are greeted by the stone outlines of a temple, in semi-darkness. There is a narrow promenade around the temple with a viewing platform jutting out into the nave. At the far end there is a illustration on glass of the god Mithras killing a bull, the key icon of the religion. Subtle lighting picks out the missing walls of the temple in an eerie grey.

The lights go out, and a sound and light installation begins. We hear muttering voices. Lights gradually pick out the walls, the Mithras figure, the features of the temple. The voices chant in Latin. It must be a wildly speculative text, since we know almost nothing about a religion which took great care to hide its mysteries from anyone except its adherents. The show comes to an end, leaving we the audience little the wiser. We then parade around the perimeter of the temple, trying to build a picture in our minds out of such slender remains.

The Mithraeum has been constructed (in stone and light) as it would have done around 240 AD, before later alterations were made. It is 18 metres long by 8 metres wide, with a central nave, a north and south aisle to its side, a well, some surviving planks, and at the far end a semi-circular apse, with a plinth bearing the glass Mithras figure. Many objects were found when the building was first uncovered, including the head of Mithras, most of which has been transferred to the Museum of London. What we see is an emptiness, the residue of a mystery.

All of the sources stress the unknowability of Mithraism. It was a mystery religion, one of those private cults whose beliefs and rituals were known only to initiates, to whom such secrecy was obviously a strong part of the appeal. It was a religion followed chiefly by those on the lower rungs of society (merchants, soldiers, slaves). So far as is known, its adherents were exclusively male. Little writing survives to describe how the cult operated, but what can be inferred from images, sculptures, inscriptions, some fragmentary texts, and the temples themselves (100 have been found all over Roman Europe) is that there were levels of initiation and membership, a cathechism of sorts, and a secret handshake. There seem to have been variations in rituals according to territory, but some iconographic images were constant. There was the god Mithras himself, always wearing a distinctive headpiece, a Phyrgian cap. There was the birth of Mithras, emerging already a young man from a rock. Chiefly there was the tauroctony, a scene in which Mithras slays a bull, aided by an array of creatures. A dog and a serpent licks from the bull’s wounds. A scorpion attacks its genitals. The bull is not having a good time.

The absence of certain information has made Mithraism a much contested subject among the archaeologists and historians. Every theory has its counter; every assertion is couched in maybes and possibles. Yet to the outsider, the appeal of Mithraism seems so very clear. Its precise meanings may be lost to us, but so it is for all past beliefs. Their actual sense disappeared with the minds that comprehended it. The attraction of Mithraism lay not just in its arcana but in its simplicity and consistency. The iconography is so narrow and particular, so reliable. It was a religion for pedants. It suited a mind that wanted the security of a belief that was uncomplicated yet could only be understood by the few. Though Mithraism presumably had its priests, it was a religion of the people (male people), owned by them rather than imposed on them, one that could be grasped because in it they saw themselves.

Across the street from the Mithraeum is another temple to another god. Mithraism is often seen as a rival to Christianity, and to see the Mithraeum with its nave, apse and chanting, along with the image of the male figure victorious suggests all sorts of parallels (Mithraism was crushed in fourth century AD by Christianity, keen to smother any rivals). Enter St Stephen Walbrook and here you have another mystery whose significance would be a challenge to determine if there were not words to help us. It is a place of pillars, funerary tablets along the walls, a high dome of great beauty, and in the centre, encircled by benches, a rough stone altar.

Did the people who visited this temple worship the altar stone? Was it used for some sort of sacrifice? (we have found no traces of blood, but that does not of itself disprove such a thesis) We have found the words ‘Henry Moore’ ascribed to this lump of rock. Was it he whom they worshipped? Or perhaps it was a wren, whose name we have found cited reverently on some fragmentary documents. What did this bird mean to the simple people, and why is it not depicted?

We may never know the answers to such mysteries.

Links:

- There is information on the history of the site, its archaeological discovery and reconstruction on the London Mithraeum site

- There is information on the Mithraeum and its objects at the Museum of London, where they are now displayed

- MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) has engrossing information on the Roman wooden writing tablets found on the original site and how they survived in its wet mud of the Walbrook for two millennia