In my ignorance, I had thought that the tomb of Philip Larkin’s poem ‘An Arundel Tomb’ was in Arundel. One day I shall be in Arundel, I thought, then I shall pop into whatever church it is and see it. So it came as a bit of surprise to be wandering through Chichester cathedral, for the first time, and there is the Arundel tomb – specifically the tomb of Richard Fitzalan (d. 1376), Earl of Arundel and his second wife, Eleanor of Lancaster (d. 1372).

The tomb is located to the north side of the nave. Two figures, a man and a woman, lie side by side, he with a lion at his feet, she with a dog. He is dressed as a knight, ready for battle. She wears a dress and wimple. Both look up, but she is turned slightly towards him, with her right leg tilted across and her right arm stretching over so her hand may be held by his right hand. In his left hand he is holding the glove that would otherwise have been on his right. We understand the message perfectly.

The tomb was made famous through Larkin’s poem, with its much-quoted final line ‘What will survive of us is love’. The poem is very much more than the sentimental notion of a love lasting down the centuries that the line is often taken to mean. ‘An Arundel Tomb’ is about the changes wrought by time, about changes in function and meaning (‘How soon succeeding eyes begin / To look, not read’), about the need in us to find affirmation in what is only stone. It sees not love but our need to see love, to see that something of us survives at all.

Inevitably, the history of the tomb throws up complications. By the 19th century the tomb was in a dilapidated state and the two figures were separated. A restoration took place the 1840s which brought them back together again, with new hands carved by the restorer Edward Richardson, as the originals had been lost. The worry ever since has been that the romantic gesture was merely a Victorian addition, false and inauthentic. Recent analysis, however, has vindicated Richardson’s work (so says a note beside the tomb), showing that he had remained true to that which the original sculptor (possibly Henry Yevele) had intended. Other tombs of couples from this period, including one of a relative of Eleanor, also have them hand-in-hand, so there is no reason to doubt the authenticity of gesture, albeit a gesture of convention. But nevertheless those are Victorian hands. The hands we want to believe that stayed clasped for over 700 years long since ceased to do so. Every restoration must mean a loss.

We know nothing of the relations between the Earl and his Countess. The ‘faithfulness in effigy’, as Larkin notes, might simply be ‘a sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace’. It is more likely to have been an indication of fidelity than romantic love, or – more brutally – of ownership.

There are many ways in which to read a church or cathedral. The buildings can be understood in purely religious terms. They can be read as architecture, filled with arches, vaults, shafts, clerestories, flying buttresses and the like, each the expression of a particular style and its adaptation through time. They can be read as tourist attractions, drawing visitors through their beauty, history, and fine objects. They can be viewed as an archaeological site. Less frequently, but just as importantly, they are expressions of power, money and the structures of the society that centred around the cathedral.

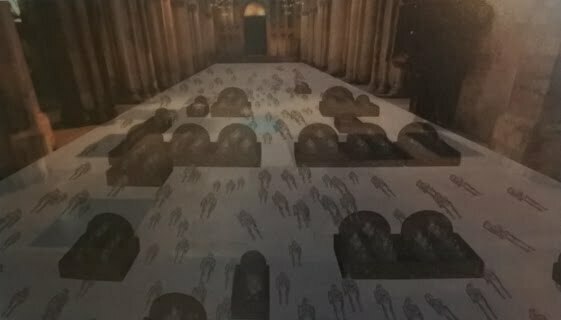

In Rochester cathedral, near where I live, there has been some fascinating work done recently with ground-penetrating radar to reveal what lies beneath the surface. What lies beneath are bodies. All over the nave are inscriptions, known as ledger stones, beneath each of which lies a burial vault. The photograph above, from a display in the cathedral, is a fanciful depiction of the skeletons that must lie below, representing 1,400 years of people with money and influence choosing to be buried as close to their God as they could.

The cathedral was the route to heaven, and the closer you could be to its heart – in life (through the pew you might command) and in death (in your choice of burial place) – the greater your sanctity must be. At the same time, the cathedral served as a manifestation of temporal power. The great of the area commanded the most prominent spots, because merit demanded it, and because money was needed to pay for it. Richard FitzAlan was one of the wealthiest persons of his time, and a handsome tomb did not come cheap. In Rochester you see not only the graves and memorials within the building, paid for by those who needed to be noticed; you also see them when alive, marking the donations they had made to the building of the cathedral. The faces of donors were reproduced as corbel heads, those faces at the end of wall supports to be found dotted throughout the building, each one a thank you note for the money, with the reward a stone immortality.

Those with a lot of money to donate might be commemorated more substantially. One of the special features of Rochester cathedral is its wall paintings. Most are worn and fragmentary, sometimes to the point of virtual invisibility, but that makes spotting them and trying to read them all the more fascinating. So, above an arch in the South transept there is the faint figure of a woman kneeling in prayer. She is no biblical figure, but instead a donor (her name no longer known to us) whose generosity was rewarded by inclusion within a religious wall painting, the remainder of which has now disappeared.

In life and in death, the cathedral reflected the society that supported it. When we walk over the ledger stones at Chichester or Rochester, we are treading on the privileged. If they could not be buried within the walls, they would be buried in the grounds adjacent. If they lacked sufficient social status, and wealth, then they were relegated to the insides of smaller churches, and then the graveyards of those smaller churches, and so onwards and downwards until all you for which you were fit was to be thrown into a pit.

All of this should be obvious, but it is remarkable how little the cathedral is explained as an embodiment of social stratification. It is commonly acknowledged just how important money was, particularly the need to attract generous pilgrims (Rochester gained a boost in 1201 when one William of Perth was murdered nearby while on pilgrimage to Canterbury, becoming a focus of pilgrimage himself and helping thereby to pay for much of the stonework). But piety and art come first. A cathedral is a place to be revered, whether for religious or aesthetic reasons.

When I walk through a cathedral, I think of neither. I am interested in the people (mostly those past, but also those present). I am interested who is commemorated there, why they needed to be so commemorated, what money and power gave them such privileges, how they squared temporal benefit with reward in the hereafter, who I am allowed to see and who is hidden. Look everywhere about a cathedral and you see power and money pushing its way to the front of the queue to heaven. Yet look more closely and those without names have left their traces too. I’ve written before about the graffiti of ages past to be found scratched into the pillars of Rochester cathedral, and what this tells of how all people could interact with, could share some ownership in the cathedral. It was the complete social space, if you look hard enough.

As in all things, when looking at the objects in a place such as a cathedral, one should ask why am I seeing what it is that I am seeing? Why these names, why these stones, why those markings, why these sentiments? A cathedral is social history in amber.

From Rochester back to Chichester. Why is the Arundel tomb there, and why is it the way that it is? It represents property, in its position, its form and its gestures – that hand in hand is an expression of possession, after all. We are the ones you will remember. We are the ones who owned and so consigned those who owned nothing to nothingness. There is no room for sentiment. What will survive of us is power.

Links:

- There is a report and photographic gallery of the ledger stones of Rochester cathedral on the Rochester Cathedral Research Guild website

- Jeremy Axelrod writes about Philip Larkin’s ‘An Arundel Tomb’ on the Poetry Foundation site, noting that “it’s important to recall that most titled families were thoroughly business-minded about marriage in medieval England”

San Francisco’s Roman Catholic cathedral burned in 1962, before I can remember, but I was able watch its replacement being built from the window of my bedroom. It is a modernist building designed by Pier Luigi Nervi and others. There was a lot of controversy about the sweeping saddle roof and other elements, such as the lack of statues, when it first opened. Now that the generation which remembered the old cathedral is passing, people like it better. The cathedral is on a hilltop and the windows give a nice view of San Francisco.

That’s a fine portrait.