I live close to England’s second oldest cathedral, which is a privilege. I regularly visit Rochester Cathedral, taking in a different feature each time, or just enjoying the the peculiar sense such places give of standing outside time through having witnessed so much of time’s passing.

It’s a small cathedral, as English cathedrals go, and not an especially decorative one. Indeed, a particular part of its appeal are the faint traces it bears of a more decorative past. In medieval times, cathedrals were rich in colour. The walls and pillars were painted, brilliant illustrations adorned every corner, especially in the upper parts of the transept and quire. Such gaudiness was stripped away by the Reformation, with only ghostly vestiges remaining. A medieval ‘Wheel of Life’ painting at the end of the quire is the most startling and complete surviving work, but elsewhere one can see figures only just emerging out of the whitened walls, such as the figure of St Christopher on right-hand pillar closest to the west door, now no more than outline and only detectable if one knows to look, and where.

On the pillars of the cathedral there are many scratching and carvings to be seen, with names and dates from ages past. I’d never given them much thought before now, only thinking wryly of how the defacements of today in time become the treasured records of history. But posters now up in the cathedral, and reports on the site of the Rochester Cathedral Research Guild, reveal that they is there is a whole lot more going on than immediately meets the eye.

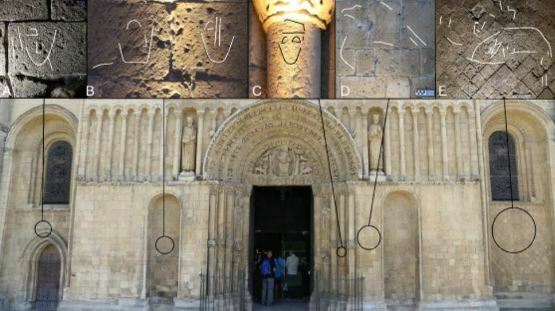

On the west facade (front) of the cathedral, and on the pillars along the nave, are some barely-discernible markings. With the guidance provided on nearby posters, one starts to see curves, hoops and circles fainted indented into the stonework. It is with some amazement that you learn from the notes provided that the outlines on the west facade (shown at the top of this post) indicate – we are assured – an eagle emblem (of St John), a Palm Sunday scene with donkey, the baptism of Christ, and the Virgin Mary.

The graffiti served different purposes. Those on the west facade indicate an artistic scheme, providing outlines for those who would then create paintings on the exterior of the building. Those inside may in some cases have been created by an artist, or a team (given some similarities in graphic design), but were often the production of members of the congregation. One pillar has several ships scratched into the stonework, probably for votive reasons, with seafarers (Rochester was a maritime port) praying for safe passage by drawing pictures of their ships. These all occur on the one pillar, indicating that there was a shrine nearby to St. Nicholas, patron saint of those in peril on the sea. Other pillars have arcs and circles, thought to be symbolic gestures for warding off evil. Other graffiti include crosses, heraldic designs, animals, symbols, and human figures. While much of the graffiti is religious in intent, it is possible some of it is simply doodling. The intent has faded along with the indentations.

The pillar graffiti would have been carved into painted pillars of red, yellow and green. While the upper parts of the cathedral, where the religious ceremonies took place, were formally and richly decorated with paintings and elaborate designs, the nave where the people gathered was plainer in style and clearly viewed as a surface on which it was legitimate for those with a good reason to do so to make marks of their faith on the stonework. Perhaps the monks would try to curb such desecration, but the evidence points to the opposite. The medieval cathedral was a public surface, inviting you to make your mark.

I know little of ecclesiastical history, but this seems extraordinary. At this time (12th/13th century) holy writ was strictly the preserve of the religious elite, with the Bible only in Latin, its understanding jealously guarded by monks, and many ordinary folk illiterate in any case. A strict divide was maintained between clergy and laity, and yet the lower parts of the cathedral were reclaimed by the people. Ownership and understanding were in each case expressed visually, whether through the fine artwork in the quire or the scratchings in the nave.

There is nothing unique about such graffiti. Many English churches and cathedrals of the same period have similar markings, though Rochester is particularly rich in ship illustrations. What struck me was, first, the ingenuity of the researchers in identifying symbols and biblical scenes from the faintest and and most elusive of outlines. Second, how the cathedral, rich in illustration and symbol, worked as a surface which invited interaction with the people who entered it. Every stone was a conduit to the sacred.

Third, the half-life of history. The graffiti, particularly those on the exterior, are barely visible. Even when a poster indicates to you where the outlines exist, it can take quite a bit of staring before you can make them out. It is sad that they are so faint, requiring the historians to take high-resolution photographs to document that which is frequently lost to the human eye. But yet they have survived for eight centuries. The markings of a moment have survived all the ravages of time, the stripping away of the paint, the graffiti of later centuries, and the irreversible march of erosion. They are still there, defying time, still believing. Something of us must survive, where we have made our mark.

Links:

- Reports on the various graffiti, together with extensive photographic records, can be found in the ‘Graffiti and Paint’ section of the Rochester Cathedral Research Guild website

- For a similar graffiti research taking place elsewhere, see the Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey and the Suffolk Medieval Graffiti Survey

- There’s a useful 2014 summary of the phenomenon of medieval graffiti in English churches on the BBC News site

- Modern graffiti is, of course, very bad. When the message ‘teen horniness is not a crime’ was spray-painted on the exterior of Rochester Cathedral in 2014, it caused much upset. But how they would love to find traces of it eight centuries from now, if only we would permit it.

Another great post, and all the more fascinating for having a subject more usually treated in florid or reverential terms. This is really how to look at the interior of a cathedral as if it were a beached hulk from another era – which in the whole they are.

Thank you Ian. Something a little different, though maybe faint traces are all that I write about.