It is one of the great questions of our time. How many roads must a man walk down? Before you can call him a man, that is. Bob Dylan posed it in his 1962 song ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, and left us to ponder its very unanswerability.

Some have tried to answer it, however. Douglas Adams, in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, has Frankie the mouse suggest that that the mystifying answer to the question of life, the universe and everything – forty-two – could more reassuringly be the answer to Dylan’s question. “Sounds very significant without actually tying you down to meaning anything at all.” Forty-two roads; a challenge, but achievable.

Alternatively, James Ball, in his recent spoof of academic studies, Should I Stay Or Should I Go?: And 87 Other Serious Answers to Questions in Songs, argues that what Dylan was really driving at was childhood physical activity. By his reasoning, the average boy should aim to walk 15,000 steps a day (it is 12,000 steps for girls, apparently). Thus, between the age of five and eighteen, when he legally becomes a man, a boy should have walked 71,175,000 steps.

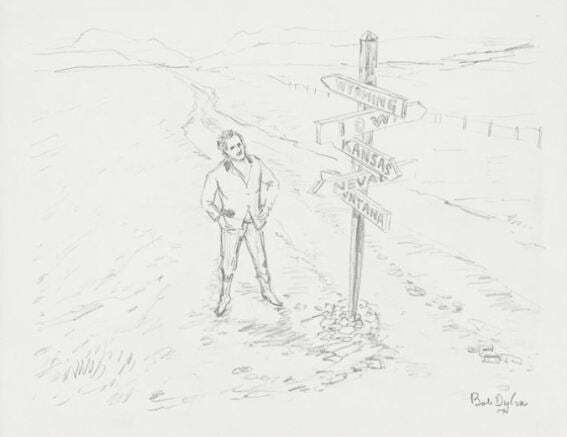

This is rather side-stepping the matter, and in any case Bob Dylan, after some six decades of reflection, has come up with the answer himself. It is five. Or possibly so. This is shown by one of the illustrations featured in Mondo Scripto, an exhibition of Dylan’s lyrics illustrated by the man himself, currently on show at the Halcyon gallery in London. A man, looking not unlike the young Dylan, stands at a crossroads, where a sign points in five directions: Wyoming, Iowa, Kansas, Nevada, Montana. Now, only one road is shown in the drawing (there’s a hint of a second), and some of the signs point the same way, but I feel that, on balance, Dylan is telling us something. How many roads must a man walk down? Five, but he won’t be able to walk down all of them. That Nobel prize was well won.

Mondo Scripto is one of the naffest things to which Dylan has lent his name. Maybe not so unutterably a misjudgement as his cover of ‘Big Yellow Taxi’, his decision to allow ‘The Times They Are a-Changin‘ to be used for TV adverts for banking and insurance companies, or the whole of Under the Red Sky, but bad enough. Dylan has handwritten some of his most celebrated lyrics – ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, ‘Desolation Row’, ‘Lady Lady Lay’ – and provided an obvious pencil illustration for each (Napoleon in rags, Cinderella sweeping up, a bed). And so we have ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ with its signpost mocking the younger man’s pretensions. The amateurishness of the results, combined with the blatant mercantilism, make you wince (there are signed prints for sale, of course). The Halcyon has previously displayed Dylan’s modest but not unappealing paintings, and his undoubtedly distinctive ornamental gates. It’s sad to see that Bob still needs the money. Whatever next?

Well, how about Heaven’s Door Whiskey? Yes, Bob has launched a range of whiskeys, taking its name from ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door‘, without a trace of shame. As the promotional blurb informs us:

Years in the making, the inaugural trilogy of expressions includes a Tennessee Straight Bourbon Whiskey, Double Barrel Whiskey and Straight Rye Whiskey finished in oak barrels from Vosges, France, air-dried for 3 years. The perfect blend of art and craft, each bottle showcases Dylan’s distinctive welded iron gates that he created in his metalworking studio, Black Buffalo Ironworks.

They are only for sale in the USA, so I can’t report on the quality, but happily Clay Risen in the New York Times has undertaken a tasting for us. His verdict is somewhat mixed, but of the Tennessee Straight Bourbon he avers that “this is a classic, no-fuss bourbon, though with more oak-derived notes — think caramel, vanilla and wood char — than you’d expect from a seven-year-old. I also smelled sandalwood, leather and linseed oil. And there’s a creamy cola note that suggests a good bit of rye in the mash bill.” Practically a song lyric in itself.

Actually, I’ll allow Bob this one. This is chiefly because of this promotional photograph, in which Dylan sits in a leather chair, elegantly attired, fine book in one hand, fine whiskey in the other, and a fine set of books on display behind. Now, it is unlikely that what we are seeing here is Bob Dylan’s library, but it’s fun to fantasise – and to see what the great man has got on his shelves.

Frustratingly, the image is not quite sharp enough to make out many of the titles, but I have spotted W.E.B. Griffin’s The Aviators, The Art Book, Alastair Cooke’s America, a large-form work on Bauhaus and another on the Surrealists, a book I can’t identify called White Light, and another prominently named on the spine as Management. There are lines of uniformly bound encyclopedias. There are few paperbacks. What the man himself is reading is, alas, not revealed. (See if you can detect more titles than me – the sharpest version of the image is at www.heavensdoor.com, if you scroll down towards the bottom). It’s an eclectic mix, from which it is hard to detect a pattern – nor indeed any sensible connection to Bob Dylan. But everyone, no matter what the circumstances, looks just that little bit better for having books on shelves lined up behind them when they are photographed. It’s a mind exposed.

Finally, there is the real thing. Released today is More Blood, More Tracks, fourteenth in the official Bootleg series, whose discs (if you count the individual discs in boxed sets) must now outnumber the studio albums he has produced. Dylan the first time round was only one part of the evolving story. No. 14 is available as a single disc, or a six-disc deluxe edition, and documents the sessions that resulted in Dylan’s 1975 masterpiece, Blood on the Tracks. Specifically, the single disc version has a selection of the original, low-key recordings made in New York (one per track from the original album, plus ‘Up to Me’), before Dylan reportedly followed the advice of his brother David Zimmerman and re-recorded some with a richer sound at studios in Minneapolis.

So we have alternative history, the masterpiece that would have been had it not been supplanted by a version still greater. David Zimmerman was probably right in telling his brother to start again on some of the songs. His argument was that the original takes were too stark, but that’s not how they sound now. Rather the word is private. Played with pared-down accompaniment (just guitar, harmonica and occasional bass), the songs are Dylan singing to himself – sometimes in the third person, sometimes the first (‘Tangled Up in Blue’ veers from one to the other), but not to us. The version of the album that finally reached the public spoke to many through a richer variety of musical textures, more obviously varied in approach. Dylan famously remarked, “A lot of people tell me they enjoy that album. It’s hard for me to relate to that. I mean … people enjoying that type of pain, you know?” That comment makes more sense when you hear the bootleg. It is music without armour, devoid of protection.

Most striking among the songs on this set may be ‘Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts’. In its 1975 release form it is a jaunty adventure with a clear cinematic quality, upbeat in every sense. The Bootleg version is downbeat, reflective, musically and in mood an extension of ‘Tangled Up in Blue’. It’s like finding that a friend who you always thought was happy has been all the while nursing a secret sorrow. It has become a ballad of lost illusions. Other songs surprise by their quietness: ‘Idiot Wind’ is a song of resignation, not overt anger. ‘You’re a Big Girl Now’ is unnervingly stark.

No one had written songs like this before, not even Dylan himself. The puzzled critical reception Blood on the Tracks originally received can now seem perverse, given the acclaim the record soon enjoyed, but on first hearing it must have been disorienting, because there were no reference points. It sounded like Dylan had returned to the acoustic style of his early career, but the level of self-analysis, as elusively expressed as it was patently raw emotion, came from another world. Dylan, always the most interesting critic of his work, said in 1977:

[W]hat’s different about it is that there’s code in the lyrics and also there’s no sense of time. There’s no respect for it. You’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there’s very little that you can’t imagine not happening.

It is storytelling, but the story is always moving away from you. It doesn’t have to ask you how many roads you should walk down. The signpost has no places upon it. All it can tell you is that the road never ends. You could be in any place, at any time. Except that, through the act of listening, you find some location after all. The booklet notes for the CD include this prescient passage from Pete Hammill’s extraordinary, Grammy award-winning original liner notes to Blood on the Tracks:

We live in the smoky landscape now, as the exhausted troops seek the roads home. The signposts have been smashed; the maps are blurred. There is no politician anywhere who can move anyone to hope; the plague recedes, but it is not dead, and the statesmen are as irrelevant as the tarnished statues in the public parks. We live with a callousness in the heart. Only the artists can remove it. Only the artists can help the poor land again to feel … the words, the music, the tones of voice speak of regret, melancholy, a sense of inevitable farewell, mixed with sly humor, some rage, and a sense of simple joy. They are the poems of a survivor.

Bob Dylan – he has always sung of modern times.

Links

- Mondo Scripto continues at the Halcyon Gallery until 30 November 2018

- Heaven’s Door Whiskey is available from assorted US locations but not in the UK – the guide on where to find it is here [Update (July 2020): – Heaven’s Door whiskey is now available in the UK – see https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=Heavens+Door&i=grocery&search-type=ss&ref=bl_dp_s_web_0]

- There is plenty of information on More Blood, More Tracks on bobdylan.com