Back in my time working as a cataloguer at what was then called the National Film Archive, then the National Film and Television Archive, and is now the BFI National Archive, we used to produce shotlists for some of the films in the collection. They weren’t, strictly speaking, shotlists, since we cataloguers seldom described the film down to the level of individual shots, but they were detailed descriptions, broken up by footage lengths. The reason for doing so was the provide a clear account of a film without there being need for someone to view the film (thus saving the print from unnecessary wear-and-tear), particularly for films that did not have descriptions in secondary sources. The focus tended to be on early films, and non-fiction.

When the Archive began in the 1930s, it seems that such descriptions were produced for every film held. As time went on, and the collection grew considerably, this was no longer possible, hence the move to selectivity. Occasionally it was useful, occasionally sheer indulgence. So far as I am aware, the BFI no longer produces such descriptions (it has curators now, rather than cataloguers, and they have to do many things). But the shotlists we produced were useful, sometimes reflected careful research, and were on occasion a thing of beauty.

They certainly looked beautiful. They were printed out on large yellow cards and filed in a wooden cabinet from another age. The look of them alone conferred importance. It was singularly satisfying to leaf through them, with great discoveries to be made each time the enquirer browsed through cards and a word or phrase caught the eye. Ah, so the camera saw that. We must find out more.

There was beauty in the words too. Your task was to sum up the essence of a film, dispassionately yet usefully, so that you were relaying the essence of that over which you had pored at the Steenbeck table viewer, stopping and starting the film to pinpoint that face, that place, those tell-take words on the side of a passing bus (nothing like adverts on buses for helping you work out when and where a film has been made).

Where are those shotlists now? Reverently stored in some BFI vault, I expect. But in the 1990s we moved to producing the shotlists electronically and then printing these out and attaching them to the yellow cards. Those electronic versions are now on the BFI’s archive database. Many of the shotlists I produced can be found there, though none has my name attached to it. I’ve listed some into which I put some effort in the notes at the end of this post, just for the record. In each case the effort paid off, because much was done with the films, either at the time or subsequently. Proof, if proof is needed, that cataloguers have to be good thing.

All of which is preamble to one film on which I spent quite some time – it would have been in the mid-1990s – trying not only describe it but to solve its mysteries, since it was unreleased, had never been finished, and had seemingly left no trace at all. It was called A World is Turning, or to give its full, putative title, A World is Turning (Towards the Coloured People).

A World is Turning was to have been a documentary-variety film showcasing talented members of the black community of Britain. It went into production in January 1948, but was never completed. It was planned to feature black musicians, dancers, sportsmen, a preacher, a surgeon and an artist, maybe more, all active in Britain, with a slender linking narrative. Its purpose was to overcome prejudice by focussing on talent and contribution to society. It believed that by portraying excellence it could influence opinion. In its small way, it looked to a better world. Or so it would have done, had the film ever seen the light of day.

At the end of the shotlist I summarised what I had been able to find out about the film. These are my notes from the time:

No details of release for this production have been traced, which was intended to document contributions to British public life made by members of the black community. The camera slates give the director as G.L. Norman and the cameraman as Bernard Hayward. From the slates, filming took place January to March 1948, but further filming in June is mentioned in a Melody Maker article. In The British Film Yearbook 1949-50 p. 429 Robert Adams is credited as having appeared in and being associate director of THE WORLD IS TURNING (sic), produced by Norman’s, 1948-49. Robert Adams, however, does not appear in these rushes. G.L. Norman ran the Norman’s Film Service [incorrect – see below], which provided a stock shot service and produced short interest films (see extract from letter below).

In Sam Edwards, New Zealand Film 1912-1996 (1997), p. 11, it is mentioned that New Zealand director and cameraman Rudall Hayward worked on a documentary, THE WORLD IS TURNING (TOWARDS THE COLOURED PEOPLE) for 20th Century-Fox. Presumably he is the same person as Bernard Hayward.

Melody Maker reference: “Felix King and his orchestra, from the Nightingale niterie in Berkeley Square, recently took part in a short propaganda film, the object of the production being the cementing of better relations between coloured peoples and white. Star of the film is Adelaide Hall and the Felix King boys are heard in a vocal accompaniment to her song ‘Gospel Train’, the special vocal arrangement being by George Mitchell. The film was actually made at the Nightingale” (26 June 1948, p. 5).

Letter in NFTVA Norman’s file from Mrs I.J. Norman, 9 October 1975: “… We were going to make a film on the negro population, filming such persons as MacDonald Bailey, Turpin Bros, Adelaide Hall, Winifred Atwell, etc. My husband’s long illness put a stop to all this developing, but all this material is incorporated in the library”.

I’m not unimpressed by the research efforts of my young self in pulling all this information together in those pre-Internet days. How on earth did I know to look in a New Zealand film reference work for information? That’s research for you – once you start looking for stuff, the stuff finds you.

But what I did not discover is why the film was made. On the BFI Player, someone has speculated that the film may have been made to coincide with the arrival in Britain of West Indian immigrants on the Empire Windrush in June 1948, but there’s nothing to support such a suggestion.

Instead the roots of the film lie deeper. An article in The People newspaper for 9 May 1948 provides some background. Its genesis came about through the meeting of Gerald Norman (G.L. Norman, the film’s director) and one Paul Maingot, shortly after the Second World War. Gerald Leslie Norman (1907-1993) was the younger brother of Emile Louis Norman (1897-1960), founder of Norman Film Productions in the 1930s and in the 40s of Norman’s Film Services, a stock footage business whose surviving collection would eventually make its way to the BFI National Film and Television Archive (I was wrong to say in the shotlist that G.L. Norman ran the company, at least at that time).

Norman served in the RAF during the war. Shortly afterwards, he met up in London with Paul Maingot, described by The People as “a former 8th Army colonel”. I’ve not been identify any Colonel Paul Maingot, but one clue might be that the surname is common in Trinidad, being of French origin. The two men had a shared interest: as the newspaper puts it, they were “determined to help right the injustices they had seen done to coloured people”.

Norman used his film industry links (meaning brother Emile, whose company produced the film) to organise the production; Maingot raised the finance. News of the intended production soon percolated through the leading lights of the black British community, all keen to take part, it was said. Among the names mentioned (in various sources) as taking part were Adelaide Hall, pianist Winifred Atwell, athletes Jack London and McDonald Bailey, boxing brothers Dick and Randolph Turpin, and actor Uriel Porter (misnamed Parker in The People article). Of these, only Adelaide Hall appears in the surviving footage, and it is not certain that the other names were filmed at all.

As noted in the shotlist, the black actor Robert Adams – a celebrated figure at the time for his leading role in the film Men of Two Worlds (UK 1946) – seems to have been involved in helping set up the film, though he did not appear in it (possibly through professional commitments – he was starring in a touring stage version of Richard Wright’s Native Son at the time). Filming began in January 1948 and continued, probably fitfully, through to June of that year. A brief mention in The Hollywood Reporter, 27 August 1948, p. 3, implies that the film was still in production to that date.

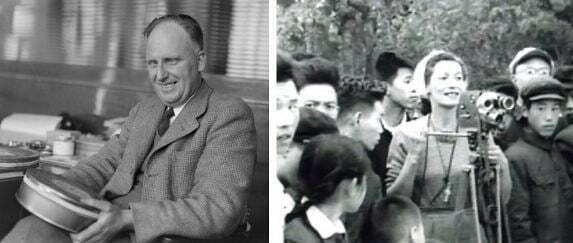

Contributing to the production’s radical edge was camera operator Rudall C. Hayward (1900-1974), who was definitely involved – there is an album of his with photographs from the production held by New Zealand’s Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision archive – though it is hard to say why he changed his name to Bernard on the camera slates. Hayward had worked in the New Zealand and Australian film industries since the silent era, producing comedies and dramas on the slimmest of budgets. With his second wife Ramai Te Miha Hayward (1916-2014), an actor and pioneering cinematographer of Maori heritage, he moved to England for a while, working on small news and documentary subjects; he as camera operator, she as sound recordist.

The couple were committed to left-wing causes – in the 1950s they made films in China, including Inside Red China and Children in China, later filming in Albania. They undoubtedly shared Norman and Maingot’s sympathies, Ramai in particular having long been the victim of racist attitudes herself. In a 1990s interview cited in a thesis by New Zealand scholar Sian Smith, Rami Hayward stated that she wrote the script for the film, as well as working behind the camera (as sound recordist, presumably). It is possible, if not confirmed elsewhere. (Intriguingly, a woman’s voice can be heard calling the takes in the hospital scenes, for which the name of director and camera operator have been wiped from the clapperboard).

Whatever the roles, there were four people involved in the film (plus Adams) who were committed to their cause. Alas, commitment was not match by ability (or finance). What survives of A World is Turning is rushes, with repeated shots, test sequences etc., which would not have made it into the finished production, but even so the evidence suggests limited competence. Filmed for the most part in a small Wardour Street studio, the lighting is poor, the interviewees painfully stilted (in particular a scene requiring multiple takes between Indian artist N.R. Rao and an utterly wooden white interviewer Miss Mitchell), the direction non-existent.

Reflecting the filmmakers’ wish to reflect different aspects of black (and Asian) British society, there is a scene in a London church with a black preacher; a scene in a club with two dancers performing to Roy Fraser and his Calypsonians, watched by a black man who protests at racial prejudice in British society before reciting William Cowper’s poem ‘The Negro’s Complaint’ (“Fleecy locks and black complexion. Cannot forfeit nature’s claim”) to an elderly white man (so not a poet himself, as I mistakenly wrote in the shotlist); and a scene in a hospital operating theatre in which a black surgeon saves the life of the elderly white man from the club.

It’s a peculiar mix, suggesting no guiding intelligence behind the filmmakers’ idealism. Only in the musical sequences does the film spring into life. In its online form it opens with an unidentified black woman at a piano, looking lost in her thoughts before the clapperboard sounds and she launches into fine renditions of ‘The Old Music Master’ and ‘Stormy Weather’. I did not know who she was back in the 1990s; I still don’t know. Can anyone out there identify her?

But the film belongs to Adelaide Hall (1901-1993). She is seen in the sequence filmed in June 1948 at London’s Nightingale Club, joyously singing ‘Gospel Train’ accompanied by the Felix King Orchestra (members of whom are clearly relishing the occasion as they sing the chorus), and at a piano with her pianist Stan, singing ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ (in several takes). Just for having Hall at her peak, the film is a treasure.

I remember seeing the film for the first time in a cubicle in the BFI basement, just willing it to be better than it was. It was meant to be a seven-reeler, but they would have struggled to get a decent two-reeler out of what was filmed.

So maybe it wasn’t just Emile Norman’s ill-health that put paid to the production (it is Emile that Ivy Norman, his wife, refers to in her note cited on the shotlist), but the reels themselves. There wasn’t a releasable film there, and they must have known it.

The People newspaper opened its article by stating that the film “will either bring fame to the two men behind it – or land them near the bankruptcy court”. Neither happened, it seems. The rushes stayed in the vaults of Norman’s Film Service, maybe used as stock footage from time to time. The company carried on into the 1970s (notably Norman Film Productions’ offices at 76 Old Compton Street in London’s Soho was where the Beatles edited their Magical Mystery Tour TV film in 1967). When Norman’s ceased trading its film library came to the National Film Archive, with A World is Turning acquired under the supplied title (Night Club Band and Singer). It was two decades later later that I looked at it (possibly the first to do so since it was shot) and started peering at those camera slates. A World is Turning? What sort of a title is that? Who made this film, and why can’t I find anything about it?

The film is now on the BFI Player and YouTube. It has been acclaimed as a lost treasure, viewed sympathetically for what might have been. The blurb on the BFI Player calls it “extraordinary”. Well, technically it’s not, but the idea of it is. That was the intention of Norman and Maingot (and the Haywards), to make an audience believe that here were extraordinary people, with their own voice. The power lay in its remarkable title, thrilling to the idea of (inevitable) change. In aspiration, if not in execution, that is what makes what we have of A World is Turning (Towards the Coloured People), revolutionary.

Links:

- A World is Turning can be seen on YouTube and BFI Player. The version of the film to be found online is in a different order to the shotlist description. All screengrabs in this post are taken from the BFI Player version

- My shotlist for the film is on the BFI Collections Search database; it is also reproduced on the Colonial Film website

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography has entries for Ramai Rongomaitara Hayward and Rudall Charles Victor Hayward

- Sian Smith’s 2020 thesis, “It came from me” – Māori representation in Ramai Te Miha Hayward’s authorship, has a page on her possible involvement with the film, based on an interview she gave in the mid-1900s with Alwyn Owen

- There was an American company Norman Studios which made feature films with black actors for black audiences in the 1920s, but it has no connection with the British Norman firm

- Other shotlists that I produced long ago include these epic and/or memorable efforts: The Open Road (1925) (co-researched with Don Swift), XIVth Olympiad – The Glory of Sport (1948), This is Sinatra! (1962), King John (1899), British Antarctic Expedition 1910-1913 (1924) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

Really nice to see deep dive into BFI cataloguing practices! You’re right, shotlisting is hard to resource nowdays …

Shotlisting felt like a luxury even in those far off days. But what has happened to those old shotlists? It wouldn’t be a huge digitisation job, and the type ought to yield reasonable OCR results.

I still shotlist very occasionally and very roughly – useful for celebrity home movies where you might want to locate a shot of a particular personality.

Hi Jo. Good to know that the tradition is being kept alive.

At the BL we’ve done some experiments with automated face recognition of notable people in news programmes not otherwise mentioned in the metadata. It’s worryingly good.