I was in the south-west of Ireland recently, on business matters but with a couple of days extra in which to explore. And so I went to Kinsale. It’s a small town, not far from Cork, located at a river mouth feeding out into the sea, its harbour facing a long cove, beyond which lies the crazily indented coastline. Two tongues of land lead out from either side, each marked with a fort, the ruined James on the western side and the better preserved Charles to the east. Furthest out is the Old Head of Kinsale, near which the Lusitania sank in 1915. The town itself is a pretty haven, with twisting streets, brightly-painted shops and any number of fine eating places to tempt the many tourists and wealthier locals (the town is known as something of a millionaire’s retreat, for all its modest appearance). Yachts tinkle and dance in the bay.

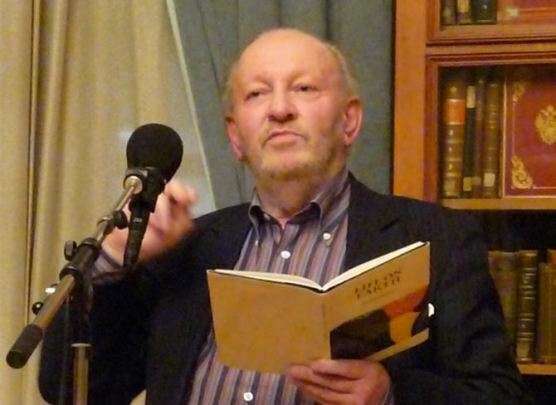

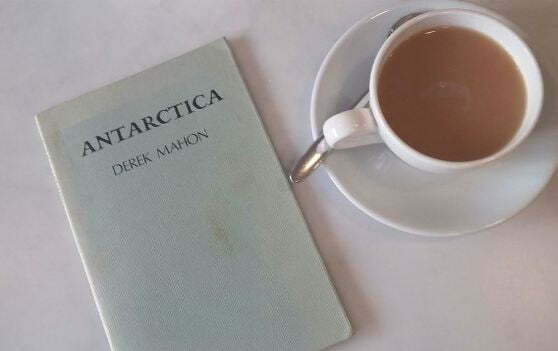

That last line is not my own, but is the reason for the pilgrimage. Kinsale is the home of the Irish poet Derek Mahon, whose writings have entranced me since I first discovered him back in my university days in the early 1980s. In his poem of hope after a time of darkness, entitled ‘Kinsale’, Mahon writes of the ‘deep-delving, dark, deliberate’ rain of the past now being replaced by ‘our sky-blue slates … steaming in the sun, our yachts tinkling and dancing in the bay like racehorses’. Transported by the sight of the town to which he moved in 1985, the year the poem was published in his collection Antarctica, Mahon concludes, ‘We contemplate at last shining windows, a future forbidden to no-one’.

So I came to see those slates, those yachts, those windows. It had not rained, and the sun was struggling to make its way through the stubbornly grey skies, but the yachts were there, and some light had got through to be reflected from the roofs. Houses looked out over the water, as though lifting frail heads to greet the hope-offering sun (to borrow from Mahon again). The place and the emotion were as one.

The move to Kinsale feels like a pivotal step in Mahon’s art. His earlier poems (his first collection was published in 1968) are of a well-travelled man who, wherever he goes, is always looking back to Ireland, south and north. Born in Belfast, Mahon’s poems of this period – technically astute, lyrical, rich in arresting language and imagery – are deeply engaged with the Troubles. Often this is refracted through thoughts of the land’s past. In ‘Rathlin Island’, the opening lines suggest a violence that could be today’s or that of lost times:

A long time since the last scream cut short –

Then an unnatural silence; and then

A natural silence …

That Irish history is often recalled through objects – Mahon has a special affinity, in his early work, for finding the life in the inanimate, as in the shape-shifting object who speaks to us in ‘Lives’ (“First time out / I was a torc of gold / And wept tears of the sun”) or, in his most celebrated poem, ‘A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford’, the mushrooms freed from darkness by a passing photographer (“Lost people of Treblinka and Pompeii! / ‘Save us, save us,’ they seem to say, / ‘Let the god not abandon us / Who have come so far in darkness and in pain. / We too had our lives to live”). At times his poems give a sense of words found written on some ancient Irish stone, whose whole meaning is now lost but whose emotion endures, as in ‘Nostalgias’:

The chair squeaks in a high wind,

Rain falls from its branches,

The kettle yearns for the

Mountain, the soap for the sea.

In a tiny stone church

On the desolate headland

A lost tribe is singing ‘Abide With Me’.

Everything connects, or else longs for a connection.

Once settled in Kinsale, Mahon turns from the traveller looking back to the person who has found his home and now looks outwards. Style and perspective both change. The poems become more discursive, more curmudgeonly (Mahon finds fault with most of that which is modern). Like many an academic in the latter years of life, he often retreats into classicism. He finds some comfort in speaking through the voices of others with his frequent translations (Mahon is an exceptionally good translator of poetry, in particular the works of Swiss poet Phillipe Jaccottet). The looking outwards can be to places once seen or friends known in the past, but often he looks no further than Kinsale itself. The town forms the backdrop to several of his later poems, the spot from which he judges time, place and himself. In ‘Harbour Lights’, published in an eponymous 2005 volume, he sets out on an evening walk:

It’s one more sedative evening in Co. Cork.

The house is quiet and the world is dark

while the Bush gang are doing it to Iraq.

The flesh is weary and I’ve read the books;

nothing but lies and nonsense on the box

whose light-dot vanishes with a short whine

leaving only a grey ghost in the machine.

It is conversational stuff, but the rambling tone is appropriate to one who sets out along some path, trying to understand where he has come to:

I was here once before, though, at Kinsale

with the mad chiefs, and lived to tell the tale;

I too froze in the hills, first of the name

in Monaghan, great my pride and great my shame –

The reference (according to Hugh Haughton, in The Poetry of Derek Mahon) is to the Battle of Kinsale, the fateful 1601 defeat of Irish lords, in which a supposed ancestor, MacMahon, played a role in betraying Hugh O’Neill’s army to the English. The place of escape, physical or mental, still entraps you with history and responsibility.

The poem ends with a question mark, which no poem should ever do (poets are here to explain, not to admit defeat). Before it does so, Mahon returns to his earlier guise in detecting the lives to be unlocked in inanimate objects, though now he is unable to read what they say:

… each bit of rock might claim

a different origin if it took its time,

the faintest starfish with its pointed wobble

might tells us otherwise if it took the trouble

and even the tiniest night-rustling pebble

might solve the mystery if it had a voice;

for everything is water, the world a wave,

whole populations quietly on the move.

‘Harbour Lights’ sees the world and the past from the perspective of a small town tucked away on the coast, a place whose offer of refuge becomes illusory. But then you walk out from the town along the coastal path towards Charles Fort, and, as the land curves, you turn around to gaze across the water. Kinsale is arrayed before you, the home of poetry. The yachts are playing in the harbour. The houses line up the slope, looking out hopefully. The sun rises in spite of everything and lights up the slate roofs. There are shining windows. Everything is going to be all right.

This is the first in an occasional series on favourite poets of mine

Links:

- The place to start with Derek Mahon is his New Selected Poems, published – as is most of his work – by the excellent Gallery Press. Among his individual collections, I recommend in particular The Hunt By Night (1982) and the translations in Words in the Air by Philippe Jaccottet

- I wrote in an earlier blog, ‘A Perfect Light’, about Mahon’s short poem ‘Epitaph for Robert Flaherty’ (i.e. the documentary filmmaker)

- ‘A Disused Shed in Co’ Wexford’ is reproduced on RTE’s A Poem for Ireland site, with an explanation of its significance and a short biography of Mahon

Derek Mahon died, 2 October 2020 – https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/derek-mahon-one-of-ireland-s-leading-poets-has-died-aged-78-1.4370324. His poem ‘Everything is Going to be All Right’ gained new popularity when it was read out on Irish television at the start of the Coronavirus pandemic.