Here’s what tomorrow looks like. At last week’s Google Cloud Next Conference held in San Francisco, Google announced a new API (application programme interface) entitled Cloud Video Intelligence. With such an application, developers will be able to detect objects within videos and make them word-searchable, as well as detecting scene changes and tagging objects accordingly. Video will become text.

This sort of application is the culmination of a lot of work on both the technological and theoretical aspects of extracting intelligence from digital audiovisual media. On the technical side, much has been going on to derive information automatically from audio and video files. This has been challenging because, unless a video comes with subtitles (which only some do) or a detailed description (which are time-consuming to produce) then the only way to gain intelligence from it is to watch it. Ditto for audio files, except they don’t even come with subtitles.

Of course it’s a good thing to watch a video to gain knowledge from it, but when you have thousands or even millions of videos, as is the case with major broadcasters and online video platforms, then the only way to extract information these at scale is to apply automated solutions – robot cataloguing, if you like.

This is not easy, because you have to train a machine to see or hear objects as we do, and for machines this is difficult. It’s easy for them to understand written words, because they can match them to dictionaries, but images, particularly images in motion, and sounds are so infinitely varied than no dictionary could ever contain them, though the human brain can.

The answer, put very simplistically, has been to train computers to recognise outlines, and then patterns and textures within such outlines, while for sounds the efforts have focussed on speech, where it is possible to match what is spoken to a dictionary or a set of phonemes (words broken down into their constituent sound parts), much as Optical Character Recognition can covert text on a page which a machine sees as images into words the machine understands as words.

The theoretical aspect hinges on an information extraction concept called entity extraction, or named entity recognition, which has been recognised for a while now as being a means to creating the building blocks of the next generation of discovery tools. Essentially entity extraction means extracting key terms from a text (such as nouns and names) and marrying these to a set of preferred terms (e.g. the text may have the words ‘Big Apple’ but the machine will know to convert this into the tag ‘New York’). If your preferred terms are shared by others, such as Linked Data promises, then you can start building and sharing resources in a far more structured and productive manner than just having a whole bunch of text and searching for words that don’t relate to anything other than themselves (which crudely speaking is still how search engines work today).

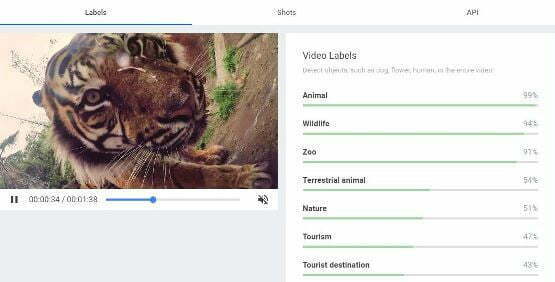

Cloud Video Intelligence API demo by by Google Developer Advocate, Sara Robinson

The magic begins when you apply entity extraction to audio and video. The Cloud Video Intelligence API, from its demos, is identifying objects such as animals, fauna and buildings, plus verbs and concepts, and tagging those points in the video where such actions occur. These tags can then be used to search through a collection of videos that have been so processed, each for a simple search (I want all videos with dogs in them) to – potentially – complex enquiries (I want all videos shot in London showing people walking in the rain). Beyond search, such data promises a rich informational structure for analysing the video and understanding it anew.

The promise of such technologies are key to what I’ve been striving towards at the British Library. The goal is to make audio and video integral to to research. To do this, I think you have to extract words from them, because words are what people search for. Yes, people will want the special information that you only get from watching a film or listening to a song, because the deepest value those media offer is one of experience, something that touches feelings rather than provides concrete information. Nevertheless there is information there to be mined, and by making this available you can reach to many different kinds of researchers across any number of disciplines. At the BL we’re experimenting with speech recognition technologies, extracting word-searchable text from radio broadcasts. The results you want not just as pseudo-transcripts (the technology seldom produces perfect results) but as those extracted entities, because with those you can create a level playing field across the different media. Texts, images, videos, audio files, can be brought together as one, and explored in common because they will share the same core discovery terms.

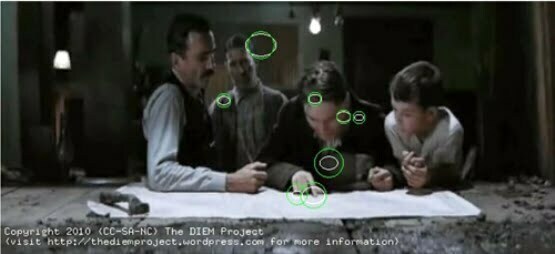

The goal is to take film out of pure film studies and to make it applicable across all manner of research enquiries. But seeing the Cloud Video Intelligence demonstrations made me think of how this will change film studies itself. Here we have the potential for new ways of seeing. A video can start to be analysed for its constituent parts automatically, constructing intelligence by enumerating and classifying what is seen. The use of eye-tracking software, which maps where the eye actually roams across on video screen as opposed to where we might imagine it rests, shows how computation can influence film studies, being championed by David Bordwell in particular.

Eye-tracking is being used to interrogate ideas of visual cognition and the aesthetic choices of filmmakers. Entity extraction could be used to deconstruct narrative, relating action experienced to objects seen, leading to new ways of mapping how a story unfolds in our minds. There’s a potential parallel with the work of literary theorist Franco Moretti (brother of film director Nanni Moretti, it so happens), whose worked has included mapping the action of classic novels to geography, revealing hidden worlds in the process.

Moretti’s work shows how difficult it is to be scientific with art works, since the beauty of works of the imagination is that they do not conform to pure quantitative analysis, nor can their essence be reduced to formula (so no robot will ever write Pride and Prejudice, though one day one might be able to produce a detective story). The digital humanities, in which some have invested such hope in recent times, is perhaps a logical absurdity. But it’s still fun to try, and in the effort towards exactitude we may end up appreciating all the more that elusiveness of art which is lies at the core of its appeal.

So, even if the data is rough, the quest is worthwhile. And tools such as Cloud Video Intelligence will be refined with other datasets, or complemented by other analysis technologies that can tell us about mood, emotions, sounds, colours and more. Analysis of individual films, or parts of films, will lead to comparisons with other films. Just as textual analysis has led scholars to identify (contentiously) the hand of Shakespeare in plays not previously associated with him, so visual-textual analysis will uncover new patterns of authorship. This sort of work has been done in longhand before now (such as Yuri Tsivian’s shot measurement project Cinemetrics), but not before have we had the possibility of eliminating the human from the computation when it comes to a film’s subject matter.

The parameters will need refining, or else all we’ll be able to do is say how many dogs, cars or buildings occurred in a film, and that won’t tell us much. But they will improve (they may even end up customisable, so I can train the API to my particular areas of interest). The hope must be that they take film studies beyond that which could be done by a patient human in any case, and that they lead to forms of discovery beyond confirmation of auteur theory. There will have to be new ways of seeing.

Imagine, for instance, if a combination of tools could be used to analyse a city film, like The Third Man for instance. There would be not only tracking of significant objects and their relationship to character and narrative, but mapping of locations to their actual geographical co-ordinates, the detection of location versus studio shots, identification of stock footage and its sources. You would open out its imaginative world. You would link that world to other resources (Graham Greene’s fictional works, other spy dramas, films of Vienna, maps, histories). You would find computable parallels with other films, or other art works, which would take your understanding of both in unexpected directions.

I remember having long conversations with the late Colin Sorensen, Museum of London curator, who knew more about London and film than anyone because he viewed fictional films about the city from the viewpoint of someone who understood the historical or metaphorical resonance of every shot. He could tell you what each building was, what its history was, which scenes were true and which fake, which documented a landmark or custom now lost, and how all of this linked up into other histories and other fictions. It was a whole other way of approaching film, as a museum in celluloid. What you could never do was to get this polymathic intelligence out of his head into some preserved and shareable form. We needed wires implanted in his brain somehow.

Now we might build that universe of interlocking associations through derived metadata, entity extraction and APIs. Unlovely words, but they promise beautiful ideas.

Links:

- There’s a handy short description of Cloud Video intelligence’s potential at Digital Trends, ‘Searching for objects and locations inside video footage is getting much easier‘

- Cloud Video Intelligence is inviting developers to sign up for a private Beta

- On Tim J. Smith’s eye-tracking studies, see his Continuity Boy blog

- For something of Colin Sorensen’s vision of film history, see his book London on Film

- I wrote on entity extraction and new ways of interrogating audiovisual media in my 2013 blog post, Metadata Matters