According to the BBC’s handy calculator, Will a robot take your job?, there is a 38% chance of my being replaced by a robot at some point in the future. Out of a list of 366 jobs, based on research by Oxford University, a curator (or archivist) comes in at number 206 of jobs at risk of automation, marked against nine criteria: social perceptiveness, negotiation, persuasion, assisting and caring for others, originality, fine arts, finger dexterity, manual dexterity and the need to work in a cramped work space. According to the research, “it’s not very likely” that I am going to be replaced by a machine any time soon.

Phew.

Were I a telephone salesperson (99.0% risk of automation), legal secretary (97.6%) or sales administrator (97.2%) I’d have reason to worry. At the other end of the scale, it looks healthy to be a psychologist (0.7% risk of automation), speech therapist (0.5%), publican (0.5%) or – safest of all – hotel manager (0.4%). Curator comes just below upholsterer and above a packer, bottler, canner or filler. I’m still trying to work out whether the ability to work in a cramped work space is to my advantage or disadvantage, but I’m happy to squeeze in anywhere.

However, this does assume that a world filled with robots doing much of the work for us will be the same as the one we currently know. Will our future, sybaritic selves, freed from menial labour and maybe even paid simply to exist (as some radical political thinkers have been proposing recently), want to have cultural things curated? Will we care about things in the same way? How will the roles that currently manage our lives change? How will the economy alter in a predominantly automated world? What ethical guidelines will be needed, and how will they be maintained? Will robots have rights?

The Science Museum’s current exhibition ‘Robots’ is filled with such questions. Opening with an unsettling animatronic baby pinned to a cushioned wall by the electronica required to make it move, the exhibition (put together by a curator, of course – Ben Russell) takes you through the automata and clockwork toys of past centuries, the robots of the imagination (mostly film) and the first mechanical men, before presenting a gallery of some of the best-known names in robotics today – Asimo (the walking Japanese robot of so many YouTube videos), Kodomoroid (the eerily lifelike newsreader), Zeno R25 (who responds to your gestures) and Harry, the trumpet-playing robot. There are plainer industrial robots on display designed to move objects around, but the crowds flock to those with cute eyes who talk back to us.

The displays ask questions about what sort of robotic world we want. Are humans worthless without work? Should we be taxing robot workers to replace lost income? (something Bill Gates has called for) And why do we want robots to look like us?

The rush for automation is becoming urgent. Japan knows that one in three of its population will be aged over 65 in 20 years time (the figure is currently one in four). They won’t have enough people available to act as carers for the needy part of this demographic. The answer will be robots. Hence the emphasis on robots with large eyes, friendly voices and ability to perform basic functions, from feeding to house cleaning. South Korea is aiming to have a robot of some kind in every home by 2020.

It’s interesting to take a look at the work which gave us the word ‘robot’, Karel Čapek‘s 1920 play R.U.R., or Rossum’s Universal Robots. R.U.R. concerns a factory that builds artificial humans. They lack any emotion and take on all drudgery, but everyone now and again one goes haywire and has to be destroyed. Eventually the world becomes dominated by robots, which start to collectivise and issue a robot manifesto. They end up destroying all humans bar one, but a male and female robot start to develop human feelings, becoming a new Adam and Eve.

Much of R.U.R. feels quaint now, but some of its insights into the nature of a robotic world resonate strongly today. There’s the heavy irony, for instance, in this speech from the head of the robot factory:

[In] ten years Rossum’s Universal Robots will produce so much corn, so much cloth, so much everything, that things will be practically without price. Everyone will take as much as he wants. There’ll be no poverty. Yes, there’ll be unemployed. But, then, there won’t be any employment. Everything will be done by living machines. The Robots will clothe and feed us. The Robots will make bricks and build houses for us. The Robots will keep our accounts and sweep our stairs. There’ll be no employment, but everybody will be free from worry, and liberated from the degradation of labour. Everybody will live only to perfect himself.

It’s a world that theorists today are now predicting – for example, there’s the concept of FALC, or Fully Automated Luxury Communism, in which employment as we know it is a thing of the past. What Čapek viewed with irony, some are now viewing seriously.

Čapek’s robots are not the tin figures of popular imagination (and of several stagings of the play) but look exactly like humans. They are organic creations, clones in effect, grown at first in a laboratory and then mass-produced in a factory. Of course Čapek is thinking of the dehumanisation of industrialisation, and well as expressing fears of what would happen to humans under dictatorships driven by heartless Utopianism. But there is also the fear of the copy, the devaluation of the unique in an age of mechanisation. This is the theme explored in Walter Benjamin’s famous essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction‘. Benjamin argued that the nature of a work of art had changed, with the copy lacking the ‘aura’, or uniqueness, of the original, though mass production could distribute such art to more people, more democratically, changing the nature of art in the process. Čapek’s robots similarly lack an ‘aura’, namely a soul, but the consequence of their mass production is that eventually they evolve, and discover a humanity of their own.

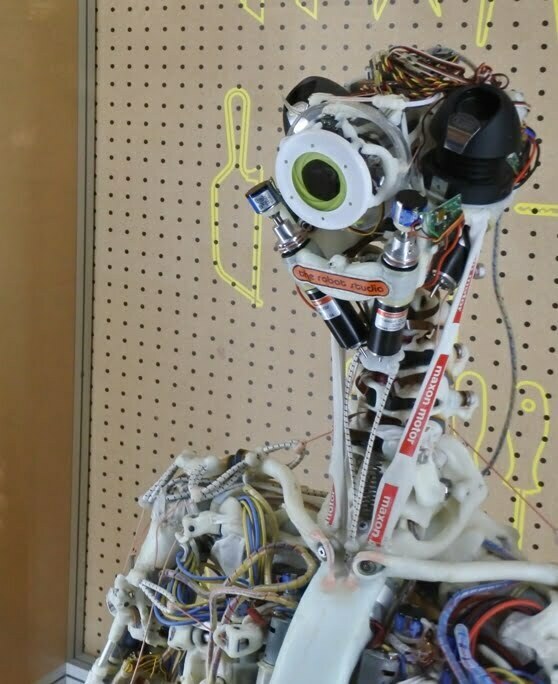

What is striking about the robots on display at the Science Museum is how they have come round to Čapek’s vision once more. Roboticists are striving to recreate the organic. Several of the displays show elaborate innards, mimicking human mechanics, with cords for sinews and moulded plastic for bones, such as Eccerobot (Embodied Cognition in a Compliantly Engineered Robot). As with the interior, so with the exterior, though the features are generally exaggerated for cartoon-like appeal. These robots will have learned from how we move, speak and think. They are copying us, in order that they may best serve us.

Of course robots are, and will be, of different kinds. The ‘robots’ we have at the British Library which fetch newspapers from our store in Yorkshire are a system of computer-operated cranes and trolleys. Other forms of artificial intelligence are no more than software programmes. The robots that are replacing elements of factory production are replacement arms and hands. Those which will take over our call centres will have only our voices. Those that will care for us, however, will look like us, reassuring us through wide eyes and friendly tones that they do not represent a threatening other but are, to one degree or other, the mirror of ourselves. Indeed all these forms of automation are mirrors of ourselves. It is just that in their proliferation, as Čapek foretold, the mirror itself will change.

So I wonder what the role of the curator is in a world of simulacra. It could be that which a robot cannot do, which might include pointing to the soul of that which has been lost. They could point to the unique creations of the past, seeking somehow to explain what uniqueness means. But I don’t think it will be nostalgic in reality – that’s just us projecting ourselves into the future. The curator of the automated age must serve that age. They will be working within a changed understanding. The human curator will have to adapt to that. Otherwise someone will programme a machine to do the work, because it will know the twenty-first century and its contexts that much better. Maybe only a machine will truly understand a machine-led world.

Links

- The Robots exhibition runs at the Science Museum in London until 3 September 2017

- Mark Mardell at the BBC has written some interesting pieces on the implication of robots e.g. The rise of the robots? and Facing the robotic revolution. See also the BBC’s Intelligent Machines report

- The Will a robot take your job? app is based on research in a paper by Michael Osborne and Carl Frey, ‘The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to automation‘

- For thoughts on humanoid robots and film, see Ian Christie’s recent piece ‘Unfair to Androids? A history of androids on screen‘

Good piece, as ever. You might want to add to your bibliography/links my recent blog for the British Academy on screen androids – http://www.britac.ac.uk/blog/unfair-androids-history-androids-screen

Ian

Happy to do so.

Further steps on the way to Čapek’s visions of human-like robots in this Ars Technica piece, ‘Get ready for robots made with human flesh’: https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/03/get-ready-for-robots-made-with-human-flesh/