One of the most notorious of all film credits is that alleged for The Taming of the Shrew (USA 1929): “additional dialogue by Sam Taylor”. Sadly the credit line is a myth – certainly it’s not appeared on any print that I’ve seen – but it’s the gag that counts. It was the absurdity of Shakespeare in Hollywood, with the film director adding his words to those of the immortal bard, that for many illustrated the supposed huge gap in cultural achievement over the centuries.

As with Shakespeare, so with Milton. His masque Comus, showing at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, boasts ‘additional material’ by Patrick Barlow. It’s tempting to think of the awkward teaming up in some cramped office of the author of Paradise Lost and the creator of the Reduced Shakespeare Company, the one penning the lyrical poetry of high moral intent, the other – to his great annoyance – aiming to throw in a few jokes to keep the impatient amused.

In fact, Barlow doesn’t make too bad a job it. Comus, originally entitled A Maske presented at Ludlow Castle, was written to celebrate the Earl of Bridgewater becoming president of Wales and the Marches, and originally featured the earl’s three children as performers. Barlow’s framing device introduces us to the rehearsals for the masque, which helpfully explain what we are to see and why, also establishing the daughter, Lady Alice, as a rebellious character. The production then ingeniously slides into Milton’s work, with Alice transported from Ludlow Castle to a wild wood, where she will do intellectual battle with the pagan god Comus. Throughout the production we are reminded that we are seeing a performance of a performance, the challenges of which are played for humorous opportunities.

Barlow’s prose and vernacular introduction works well enough, his conclusion less so. There is a rude transition from Milton’s words to Barlow’s conclusion, when Alice is given words of defiance that are all too obviously of the 21st century rather than the 17th, though as they are given in verse some in the audience might have wondered if this was Milton the proto-feminist speaking – until Alice tells her father that she is an independent being and he can ‘like it our lump it’. Though there is logic to it (we cannot but wonder at the real-life Alice’s mistreatment at the hands of her family) it’s an inelegant end, more worthy of Sam Taylor than Milton.

The theme of Comus is chastity. It’s not an easy subject to make credible for a modern-day audience, but we can appreciate well enough that what we are seeing is a battle between the carnal and spiritual, and that Milton is using all of the poetic powers at his command to argue for the forcefulness of good for its own sake. The framing device makes us understand the social contexts, but is defeated by the work’s moral intent.

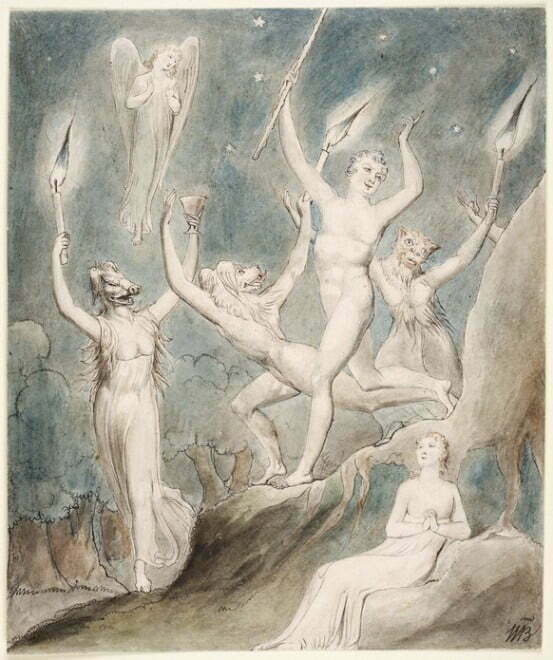

The story is that the Lady Alice, playing herself, becomes lost in a forest. She comes across the god Comus, son of Circe and Bacchus, disguised as a shepherd. In the company of a gang of travellers that he has turned into beasts, he leads her to his palace where she is held fast to an enchanted chair while Comus tries to get her to drink a magic potion by which she will succumb to his desires. She defends her chastity through argument, then her brothers (also playing themselves – Alice was 15, they 9 and 11) burst in to rescue her. Comus escapes, but the magic spell that binds Alice to the chair is broken by a nymph of the River Severn, Sabrina. The children are then led back to Ludlow by an Attendant Spirit.

Like most if not all masques of the Jacobean era, Comus in synopsis comes across as bonkers. Masques were dramatic entertainments in which drama was subservient to spectacle, music, allegory and moral. Though their ancestry laying in the popular mumming plays, they were put on for private, high society audiences, at court or in grand homes. The performers were amateur, frequently featuring the gentry themselves (as with Comus). Many of the great dramatists of that age wrote masques (Jonson, Beaumont, Chapman, Middleton, but for some mysterious reason not Shakespeare, though several of his plays feature masques), because the money was good and they were probably flattered by the aristocratic audiences they could draw. Masques were often hugely expensive to put on, catering for the vanity of all those concerned.

Viewed today, many masques are quite baffling. Their elaborate conceits, coded references and rococo language make it hard for anyone outside an academic exceptionally well attuned to the tastes and personalities of the age to work out what anyone made of them at the time. To pick the titles of some Ben Jonson masques for example, what to make of Love’s Triumph Through Callipolis, Neptune’s Triumph for the Return of Albion, News from the New World Discovered in the Moon, or Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists at Court? They made sense at the time to the few at whom they were aimed, leaving posterity perplexed.

Comus is a little different. Though it has its songs and opportunities for spectacle, and though the characters give long verse speeches rather than engage much in dialogue, it can function as a drama, and certainly has had a life way beyond the specifics of its intended performance on 29 September 1634 in the Great Hall at Ludlow Castle. It was frequently revived throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, productions that emphasised the spectacle and usually added much extra material in the way of songs, dances and stage effects. At times such productions retained Milton’s original moral intent, but more often Comus served as a vehicle for the lavish and lyrical. Artists including William Blake, Samuel Palmer, William Etty, Edwin Landseer and Arthur Rackham has illustrated scenes from the work, as Comus found itself variously interpreted to match the temper of the times.

It survives best today through two passages of some of the finest verse in the language. From primary school I have known ‘The Star That Bids the Shepherd’s Fold‘ and ‘Sabrina Fair‘, perhaps the loveliest song in the English language:

By the rushy-fringed bank,

Where grows the willow and the osier dank,

My sliding chariot stays,

Thick set with agate, and the azurn sheen

Of turkis blue, and em’rald green

That in the channel strays,

Whilst from off the waters fleet

Thus I set my printless feet

O’er the cowslip’s velvet head,

That bends not as I tread;

Gentle swain at thy request

I am here.

In the Globe production, ‘The Star That Bids the Shepherd’s Fold’ was rather more rambunctious in performance than I was expecting, though given that it is spoken by Comus with his crew of earthy monsters about him it was appropriate enough (“What hath night to do with sleep? Night hath better sweets to prove”). But ‘Sabrina Fair’, bar one unnecessary comic aside, was performed exquisitely (Natasha Magigi as Sabrina, rising from a river beneath the stage), bringing a small tear to the eye.

The reviews of Comus have all said how funny it is, but Comus is not a humorous work. I’m uneasy about productions that must translate the original intent into something that finds favour with the morality of our times – the masked masque, perhaps. Yet what else can we do? ‘A Maske presented at Ludlow Castle’ was coded for a particular audience, on a particular date, and a particular place. It was not intended to make sense on any other occasion, even if Milton saw that it enjoyed an extended life through publication. Plays, and masques, change each time we perform them, because we change who see them. They must be decoded for our times if they are to be anything beyond a mere academic exercise. We in the audience were now the privileged few, who demanded that it pander to our tastes and expectations. Like it or lump it, Milton and Barlow had to find a way to work together.