Back in 2009 I was set an interesting challenge. I was invited on behalf of a group investigating the lives of British women who had worked in silent film to take on the research into one of those about whom nothing much was known. I picked the name Mary Murillo. I knew nothing of her, and her name was absent from all modern film histories and reference books. But the credits on IMDb showed someone who had had a career as a scriptwriter in America and Britain in the 1910s and 20s, so I set out to find what I could find.

It has been quite a journey. My initial findings were published towards the end of 2009 on my Bioscope blog on silent film. I used her story as an example of just what could be done for an obscure figure with the online resources available, particularly family history sites, as encouragement for others to go out and do the same. It was an example of digging around among the minutiae of film history, but so what? As I wrote at the end of the blog post:

Why research someone so obscure? You have to ask? Is there any nobler activity out there than to recover a life? Certainly it is always excellent when anyone recovers a corner of history that has been lost or ignored, however small it may seem. It’s a contribution to knowledge, and telling us something that we didn’t know before is a whole lot better way to spend your time as a researcher than re-telling that which we already know. So go out and do likewise – and then tell the world about it.

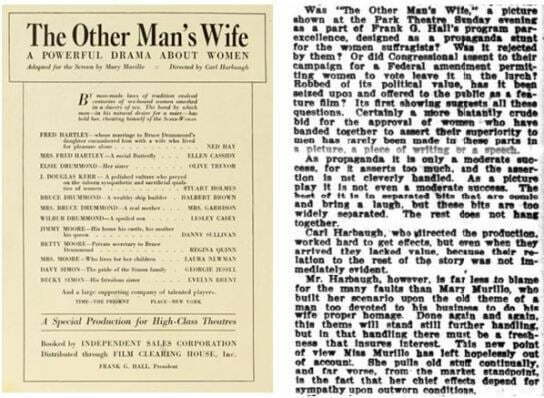

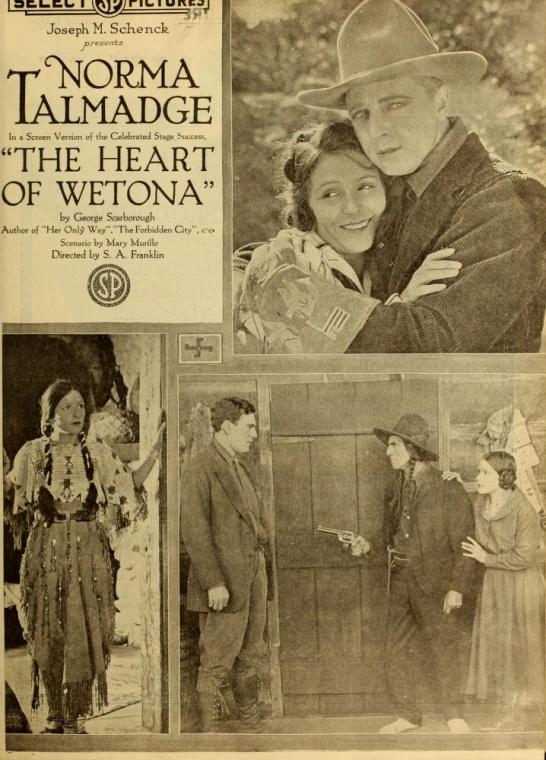

The post proved to be a popular one, and I know that it has encouraged a number of people to pursue similar topics. What I discovered was that Mary Murillo was a major scriptwriter in 1910s Hollywood who had been abandoned by film history. She was not a great talent, but she was a highly competent professional, who at her peak was the leading scenarist at the Fox Film Corporation and the muse of choice for such stars as Theda Bara and Norma Talmadge. She was born in Bradford in 1888 of (apparently) Anglo-Irish stock. She travelled out to America in 1908 with the hope of making it as a stage actress, adopting the name Mary Murillo (having been raised as Mary O’Connor). She toured the country for a number of years without making much of an impression at all, then around 1913 tried a different tack and starting writing film scenarios. She was an almost instant success. Within four years she was earning a reported $25,000 a year (that’s around $387,000, or £245,000 in today’s money). She started with the husband-and-wife team of Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber, moved to Fox, went independent in 1917, then became lead scenarist for the major US film star of the immediate post-war period, Norma Talmadge.

She also proved to be quite a character. Proudly independent, she was never a one for paying bills, and left a trail of chaos behind her. A New York Times report in 1923 tells of their sheriff of her New York home by a deputy sheriff in pursuit of defaulted payments. The law seized “tapestries alleged to be valuable, a mahogany grand piano, phonograph and a quantity of records, a lot of silver and a leopard skin”. But Mary had moved on.

She had moved back to Britain and started writing scripts for Stoll Film Studios, before getting involved in setting up new film companies with figures such as Edgar Wallace, then moved to France and played a prominent role in scripting some of the first French talkies. Thereafter her actions became hard to trace – one credit on a British feature film in 1934, then nothing until she popped up in London supporting Belgian refugees in 1941. And, after that, she disappeared.

I was pleased with the blog post, but frankly the research wasn’t that great when I did not know when she died, whether or not she had married, whether there were any children, and what happened to her for the best part of a decade. I knew the names of her sisters but not of her parents, and there were many puzzling holes in the biography. I had found just the one photograph of her. In part the problem was caused by someone who worked under a pseudonym, while Mary O’Connor is not an uncommon name, so there were many false leads. But there I left it, having achieved the main point of showing how a life could be reconstructed, at least in part, and why it was good to do so.

But these things do not leave you alone. A year later, while proof-reading a book on colour film history, I stumbled upon the information that she had been heavily involved in promoting a French colour film process, Francita, in Britain (where it was called Opticolor), during the mid-1930s. The business had ended disastrously, but it was clear that she was still in the film business and in earnest pursuit of her next fortune. New resources also appeared, notably the Media History Digital Library of digitised film journals (mostly American) and the British Newspaper Archive, which added extra information on her career, albeit most of it advertisements for films that she had written. But I left the story to one side once again.

Then, around a year ago, I was asked by a publisher if I could convert my blog post into an essay for a book on women’s film history. I did so rather sloppily at first, then realised I had to get back properly into the research once again, and answer those unanswered questions if I could.

The results were startling, at least to me. The gates were opened by the discovery of her family, via entries made on the family history site Ancestry which hadn’t been there in 2009. I discovered that she had been married (or was partnered, as there was no record of a marriage) to a French cameramen, Maurice Velle, who was the son of Gaston Velle, a revered figure in early film history for the glorious magic films he made for Pathé in the 1900s. She and Maurice had had two daughters, who were both still alive. Mary had used three surnames at different times – Murillo, O’Connor and Velle – so it was no wonder it had been so hard to find certain family history information about her.

Indeed the family did not known much about her early history or parentage, but now I had the bit between my teeth. I found her death date (she died in 1944, registered under the name Velle), while her parents were Irishman Edward O’Connor and Yorkshirewoman Sarah Sunter – or so it appeared, because there were oddities in the records that just didn’t add up, including an American step-sister Isabel Daintry (who was a minor film actress in the 1910s) for whom I just could not account.

Finally I found enough of the story through a mixture of deductive logic and luck for it to start to make sense. Mary was born illegitimate, father unknown. Some years before her mother Sarah had emigrated to America as a newly-wed, returning a year later with a young daughter (Isabel) after her husband died. Mary was born a few years later. Six years after that Sarah married Irishman Edward O’Connor, a Roman Catholic and a successful businessman. They had three daughters, and Edward brought up all five as O’Connors. Though they maintained roots in Yorkshire, the family led a cosmopolitan life, spending time in France and Ireland.

Engrossing stuff. But why had I got so engrossed in someone else’s family history? It’s hard to say. I wasn’t pursuing the story through a particular passion for her films. It was just a task that I had set for myself. I knew the territory, and there was the triumph of discovery.

And there was that recovery of a life. Because what emerged was the story of a survivor, who adapted ingeniously in face of the demands of a hard world. I don’t know what she knew of her real family history; she brought up her children to believe that they had Irish ancestry, when in fact they had none, and strongly asserted her Irishness in a 1917 interview. She appears to have revered her father (though he wasn’t her father) but she and her sisters did not always see much of their parents, as they were dispatched to convent boarding schools at a young age – a pattern she then repeated in adult life by leaving her own daughters in boarding schools. She masked her past through an assumed name, found a fortune and a little fame (as much as a female scriptwriter was ever going to get), crafting expert vehicles for women film stars who needed to display emotional triumphs won after facing romantic dilemmas with a moral twist. She owed nothing to anyone (even while she often did), kept on moving, and adapted to the changing world of film far better than most of her contemporaries. Her story illustrates the great changes in film production over its first forty years, from a curious addition to variety theatre programmes to the era of the big film studios. Her partner’s father had begun his film career in the 1890s with the Lumière brothers; she ended hers working for J. Arthur Rank (in his Religious Films division, where a colleague was the young Peter Rogers, of later Carry On fame). Like her heroines, she dreamed grand dreams, and was a survivor.

Above all, her story shows the importance of women’s film history for understanding film history. The silent era of film has attracted a lot of interest from historians of women’s film, because of the relatively large number of women involved in the industry on the creative side in these formative years. It wasn’t exactly a utopia, but in the era before the major Hollywood studios had fully established themselves, there were opportunities for independent spirits such as Alice Guy, Lois Weber, Nell Shipman, Elvira Notari and Esfir Shub to direct films with a distinctive vision (only one woman, Dorothy Arzner, directed a Hollywood feature film in the 1930s). There were also numerous women editors, scriptwriters, producers, camera operators, costume designers and studio owners. They were still very much in the minority, and often had to fight too hard for the few opportunities that came their way, but they were nevertheless beneficiaries of the changes in society that were causing the role of women to be re-evaluated for the better. However, histories such Mary Murillo’s do not just show how women struggled against the odds to gain some foothold in a new industry. Their presence and their creative input must make us challenge received understanding about where the significant points in film history lie. It is not a history of the works of great men (Griffith, Chaplin etc) whose fortunes a few women echoed on the fringes of the industry. It is a history that is enriched by a fuller understanding of all that women brought to film in its developing years – as producers, performers, commentators and audiences. We see film history differently. Mary Murillo was important because she was Mary Murillo.

At which point we must look to her films after all. This June/July, the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna will have a short strand on the films of Gaston Velle, Maurice Velle and Mary Murillo. Entitled The Velle Connection 1900-1930: Gaston, Maurice and Mary Murillo, it has been co-curated by Marian Lewinsky and myself, and brings together some of the best of the trio’s surviving films. Gaston Velle’s féerie films will attract the most attention. He was one of those several magicians of the 1890s (his father Joseph was also a magician) who took up film as an extension of their magic skills. He made some truly magical films in France and Italy, among them Japonaiseries (1904), La Poule aux oeufs d’or (1905) and La peine du talion (1906). There is a particular grace and style to his films which mark them out as different to the ostensibly similar films of his better-known contemporaries Georges Méliès and Segundo de Chomón. Unlike his daughter-in-law, he did not adapt to changing times, and had left the industry by 1914, his kind of film having lost favour with audiences. Now his surviving works can be found all over YouTube, enchanting all those who find them, more than a hundred years on.

His son Maurice we know less about. He was a cinematographer on a number of French feature films in the 1920s before he turned his attention to developing his invention, the Francita colour cinematography system. He was a skilful cameraman whose work is more than worthy of rediscovery, as the sumptuous films on show at Bologna will demonstrate: L’Île enchantée (France 1927) and especially the little-known La Princesse aux clowns (France 1924) for which Mary Murillo provided the English titles. La Princesse aux clowns, a frothy but lavish tale of a reluctant prince and his determined bride, feels very much like a Velle/O’Connor family film, with its theme of stage performance echoing Gaston’s pre-film career, and a sly reference to a Murillo painting in the intertitles. The director was André Hugon, and the story was by Jean-José Frappa, but this is the O’Connor/Velle family as auteur, the meeting point of stage and film, Britain and France, Hollywood and Europe, prince and princess.

Mary Murillo will be represented at Bologna by La Princesse aux clowns; by The Heart of Wetona (USA 1919), an intriguingly-themed and beautifully-shot Western with Norma Talmadge as a half-breed American Indian torn between love and tribal loyalty; by the early talkie Mon gosse de père (France 1930), with Adolphe Menjou; and the charming My Old Dutch (UK 1934), directed by Sinclair Hill. Around dozen of Murillo’s films survive, and at least fourteen scripts. But her real creativity was in the life that she led.

The essay based on my original blog post will be published in Doing Women’s Film History, edited by Christine Gledhill and Julia Knight, courtesy of University of Illinois Press, in November 2015.

Links:

- My original Bioscope blog post, Searching for Mary Murillo, describes how I went about finding what I knew about her up to 2009

- There is a more up-to-date biography on the Women and Silent British Cinema site, and her Wikipedia page has the basics

- The Bologna festival runs 27 June to 4 July and has strands on Ingrid Bergman, Leo McCarey, Buster Keaton, jazz films, and Technicolor, the Velle/Murillo section and a great deal more over its eight days

- The BFI DVD release Fairy Tales has examples of Gaston Velle’s Pathé trick films with beautiful stencil (artificial) colouring

- The lives of many early women filmmakers can be found on the Women Film Pioneers Project website

Nice work, Luke–from what you say here, I take it you did talk to her daughters? Thanks for posting your update information.

Hi Joan – both daughters (one in USA, one in France) are quite elderly and no longer able to provide information, alas. I have been in touch with family members further down the line, who have been most helpful (and I think I’ve been a help to them, as parts of the family history had been a mystery).

Wow! That’s fabulous and congratulations on your upcoming presentation in Bologna! I read with interest back in the day the 2009 Bioscope posting, so this update is really fabulous!

Hi Donna – thank you. Hard to believe it’s over five years since I wrote that original post. Where has the time gone?

Hi Luke,

I have known one of the daughters personally since 1998 (the one who lives in France). Over the years she has become a dear friend. She often spoke of her parents and her childhood to me. Your post has helped fill in some of the details and confirm the seemingly crazy stories she told of her past. Thank you for that. I’d like to attend the festival and see some of the Velle films but can’t seem to find the exact screening times on the website. Any details you can provide would be greatly appreciated.

Hi Kathleen,

Thanks for adding this comment. It is a remarkable family history, some parts of which I hope I’ve helped to pull together. The dates of specific screenings at Bologna have been published as yet, but I’ll email you with the provisional dates as I have them.

Luke

A fine history and critical assessment of Mary Murillo’s career by Christina Petersen has now been published on the Women Film Pioneers Project website: https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pioneer/mary-murillo/