Just under thirty years ago I went to a tiny cinema, the name of which escapes me, somewhere off Piccadilly, London, to see a dramatised documentary about the Irish painter William Scott. It was directed by the painter’s son, James Scott (who had won an Academy Award in 1983 for the Graham Greene short film A Shocking Accident), and was called Every Picture Tells a Story (UK 1984). Humble a production as it was, it nevertheless made a great impression on me. It told the story of the painter’s childhood up to the time when he left Northern Ireland for the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

It was a costume drama intercut with commentary from Scott himself, and three elements have remained stuck in my memory, along with the general sense of a fine film. One was when the teenage Scott is asked by an art teacher (played by Natasha Richardson) to draw an apple, to show what he can do. The very simplicity of this made a great impression on me. Another, oddly, was the abrupt ending, when Scott says that everything in art was changed by Cezanne, and the film ends there (I now know it was intended as part one of a trilogy, but the remaining parts were never made).

Third was the film’s most distinctive feature. One would witness a scene from Scott’s childhood, played out by actors, when abruptly the film would cut to one of his abstract or semi-abstract works, as a kind of flashforward showing how what impressed the child’s mind was later recapitulated as art. It was a startling, exhilarating innovation, which impressed me as a film enthusiast and turned me into a lifelong admirer of Scott’s art. The visual coup stayed with me, and though I never had the chance to see the film again I filed it away as a hidden gem, forever confirmed as one of my favourite films of that period.

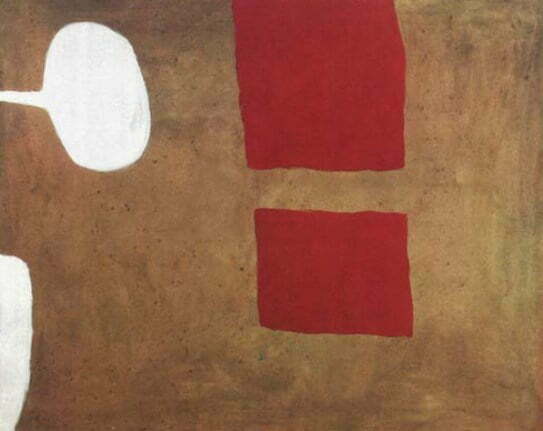

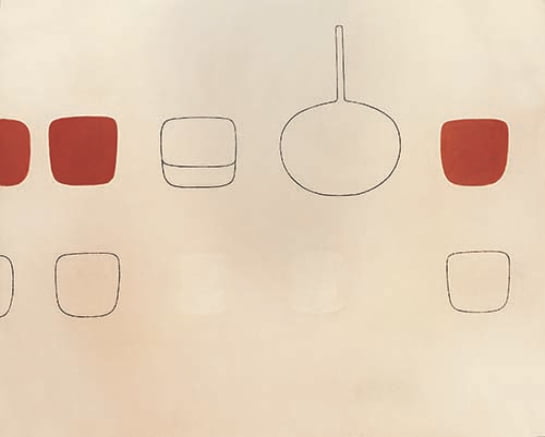

2013 was the centenary of Scott’s birth and was marked by a major exhibition at the Ulster Museum in Belfast. I managed to get there on the very last day of the exhibition, 2 February 2014, when it so happened that there was screening of Every Picture Tells a Story. Would it still stand up? I spent the morning touring the exhibition, a thrilling experience being in the huge white space of the Museum’s main gallery, with Scott’s immaculate works all about me, and not a soul there (bar the occasional guard). What a rare joy to have an art gallery all to yourself. Scott’s paintings are best known for their use of domestic images such as tables, saucepans, jugs and cutlery, and for the skilful arrangement of line and plain blocks of colour. The works are abstract to a degree, but figurative also – they relate to something, yet need not relate to anything. To be in a room filled with them is heavenly.

And so to the film, shown in the Museum’s lecture room. It did not disappoint. I’d forgotten much of it (so mostly it was like seeing the film for the first time), but its special economy of style, at one with its subject, was what arrested me back in 1984 and which remained true. The film shows the Scott family living in Scotland when the father (a loving portrait played by Alex Norton) returns from the First World War. He moves the family to his home town of Enniskillen in Northern Ireland and makes his living as a sign painter. Among his large brood of children, his son William is drawn to art, sketching objects on the kitchen table and helping out with his father’s work. The father takes him to a local art teacher, and after the father dies in an accident the local Presbyterian community see to it that the talented son is able to go to the Royal Academy in London.

The narrative is irrelevant, however. What matters is what is seen, and felt. There are the saucepans, plates, pots and tables that most obviously recur in Scott’s later art, which is revealed – as I remembered – by the startling cuts from figurative memory to abstract expression as the film cuts from story to paintings. There is the collapsing of time, between the unfolding story and the figure of William Scott himself, heard speaking but filmed sitting wordlessly, and between past and present most ingeniously (and economically) where Scott’s father prepares to go on an Orange parade in the 1920s before we see a 1980s parade taking place outside. Nothing, incidentally, is made of politics or religion, in the film. It is simply a part of the picture, of what is seen and felt.

Which leads me to the film’s title. This was the part of it that had always bothered me. ‘Every Picture Tells a Story’ is a tired cliché, and an odd thing to say about art works which tend towards abstraction. The beauty of abstract art is that it does not tell a story. It is not dependent on narrative, be that figures arranged in a recognisable setting (e.g. historical) or a portrait, where we are encouraged to think who that person was, what thoughts lie behind their eyes. It is art that requires a key. In the film someone asks the young Scott why a book of paintings has no descriptions to say what the pictures signify, to which he replies that “pictures are for looking at – the picture tells the story”. The real-life Scott then tells us that “every picture tells a story”.

This is not ‘story’ as in narrative, but the abstraction of things seen and felt. They signify something of the story of William Scott, and that was obviously part of the filmmaker’s intentions, and his reason for the choice of title. But what ‘every picture tells a story’ really means is that the picture renders the story unnecessary. The pictures do not need a narrative explanation. The paradox could have made Every Picture Tells a Story a bad film, but instead it’s a film that is able to have it both ways. The pictures spring out of the story of William Scott, and they have no story at all. All that is there is all that you can see.

I returned to the gallery after the film screening, and passed through the rooms once more, which were now filled with people. The spell cast in the morning had been broken. Too many other eyes were looking, interpreting, confusing the narrative, breaking up the abstraction.

But do we ever have pure abstract art? Every picture plays upon something in our memories, even the simplest shape or a single colour must connect with something in the way that we see the world, or we would not see the picture at all. Art, in that respect, is the distillation of experience. Perhaps purely abstract art only exists in an empty gallery, where no one can see it, where there are no stories to be told. So I like to feel that, being in that gallery in the morning, when there was only me, that I might have come close to seeing it.

A version of this post is included in my book Let Me Dream Again: Essays on the Moving Image (Sticking Place Books, 2025)

Links:

- The official William Scott website has examples of his work, a biography, details of collections, news and events

- The Ulster Museum site has details of its collections, exhibitions and events

- James Scott’s personal site has information on his artworks and films, including Every Picture Tells a Story

- An informative interview by Kevin Gough-Yates with James Scott on the making of the film

Hi Luke

Thank you for your kind and perceptive comments on my film Every Picture Tells a Story. Clearly you got it and that makes me very happy. I had not read this review before until I was sent it by one of the staff at Eton College where I recently presented the film in conjunction with a little William Scott Still Life show that is on there. Do try and see it if you can. It is worth the trip out to Windsor.

Regards

James Scott

Hi James,

Thank you for your comment. It’s good to know about getting it – I tried to. I will certainly get to the Eton exhibition if I can.

Luke

The BFI is a releasing a DVD of Every Picture Tells a Story plus some short films about artists made by James Scott:

http://shop.bfi.org.uk/pre-order-every-picture-tells-a-story-the-art-films-of-james-scott.html

Hi.. I stared in a small documentary in dennistoun Glasgow a row of old shops.. A small part.. I was the paper boy.. I was to walk into the barbers and say the tele telegraph Mr… As a man was having a haircut or shave… Explaining he was going to London England maybe he said…

It was called… EVERY PICTURE TELLS A STORY…

I recall it showed on channel some years on… I must have been around 10yrs old… Great wee memory.